This post is part of a series on estimating population sizes:

The Kingdom of Tamego

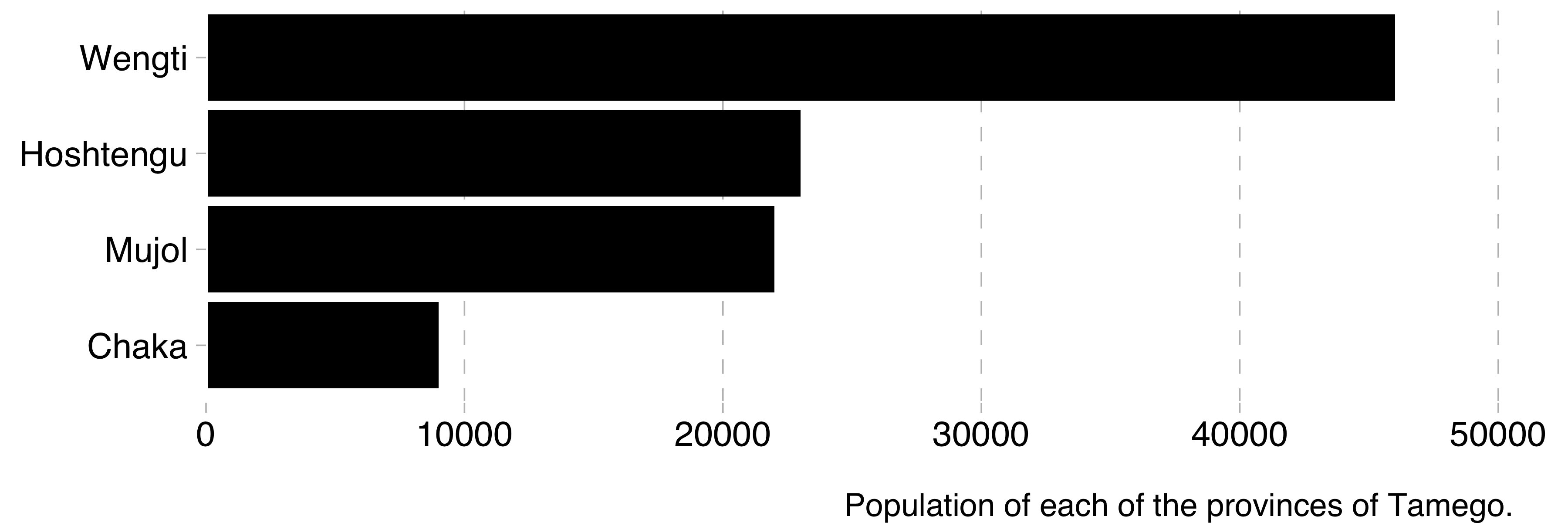

Imagine a country with four provinces. We can call it the Kingdom of Tamego. Its provinces are Chaka of the high mountains, Wengti of the wide coast, Mujol of the deep woods and Hoshtengu of the shining plains. There was once a civil war in this kingdom, in these four provinces. Three factions warred: the Angu rebels, made up mostly of peasants and labourers; the Zid, a minority people who sought autonomy; and the king himself, who fought them both from his stronghold in Wengti. The war was vicious, but after two decades of blood and fire the king had all but crushed the rebels and the separatists. The cemeteries were stuffed like the bellies of the rich. Families had betrayed their neighbours and been betrayed by them. All dissent had been squashed. And those who gather the souls into the next world were now left with fields and acres of them to reap and harvest.

After the war ended, the king, having carried out and completed his life’s work, died and passed away. His daughter became queen. The queen sought a path of reconciliation. As part of the reconciliatory process, she asked a trusted official to find out how many had been killed by each side during the war, in order that the communities of the slain could be recompensed. The official, unable to think of a greater duty than to serve the queen of Tamego, agreed.

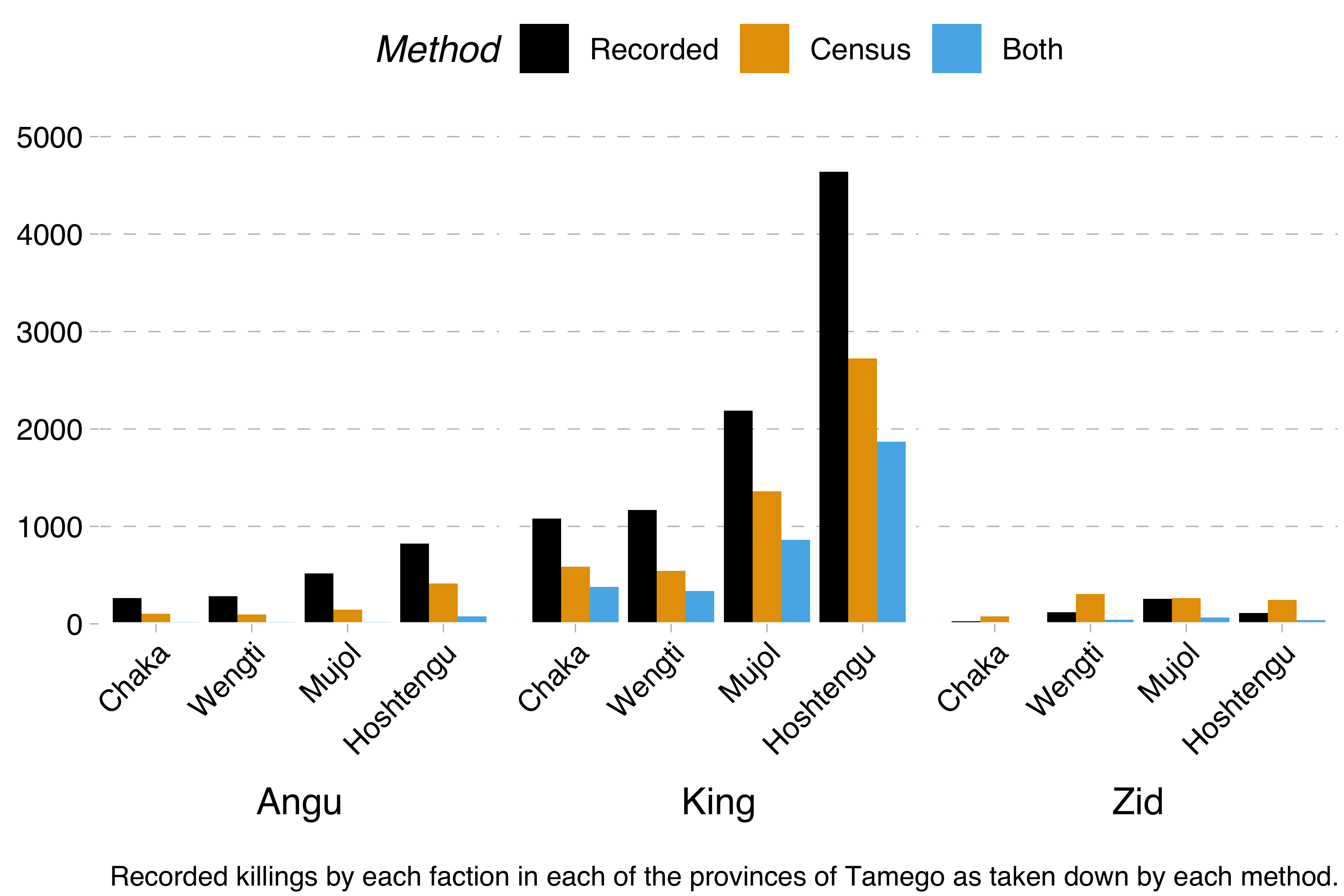

The official went to all the ministries and asked to see their records. He found first the military’s own records of those who had died. These records were considerable. But everybody knew that, though the military recorded soldiers’ deaths ably though not perfectly, their records of civilian deaths were erratic at best. The military records had gaping, rebel-shaped holes in them.

Then the official remembered that the last census, carried out in the previous year, had included questions on how many in each family had fought in the war, which side they had fought on, whether they had been killed and which side had killed them. This seemed like a promising source. But everybody knew that the census response rate was low and lower still among the Zid and among Angu sympathisers. The census was not a representative sample.

All this happened during winter. The cold air felt like porcelain on one’s skin. Rain swept in from the sea and battered the fields, the woods, the plains and the mountains incessantly. People had a hard time going out at all, enduring the sunless days; and they would wonder, how is it that something which in small doses is not only bearable but even essential to life, when its dosage is increased, can become fiendishly unbearable to it?

As for the official, he deliberated. The true numbers were shut off from him. How should he infer them? Of course he could just add up the numbers in the official records and the numbers from the census and subtract from the result those that occurred in both of them. That would give him a lower bound for his estimate, but no more than a lower bound. He needed an oracle’s insight. So he went around the city, from house to house, meeting with Tamego’s eminent historians and mathematicians, until he came at last to the house of an old, wart-nosed lady, of whom the other scholars spoke with a mixture of fear and contempt.

“What have I done, young one, that you should disturb my peace and privacy?” she said upon seeing the official. “Well, tell me and let me know. I am not clairvoyant and neither do I have time for pointless talk.” The official gave a summary account of his problem. When he’d finished, she stretched out her arm and said, “You must go to the shimmering plains of Hosthengu. There you will find a man with a pauper’s costume and one hand missing. He will tell you all there is to know.”

The official left the wart-nosed lady’s house giddy with joy. He did not know that, in fact, she loathed the queen and had as soon as she had set eyes on him decided to send the official, this slack-tongued queen’s man, to the furthermost province in Tamego, where no answers could possibly be found to the questions he posed.

The official had never previously travelled outside his native province, but went to Hoshtengu in search of the one-handed man who dressed like a pauper anyway. The journey was perilous but he, undaunted by the dangers and heartened by the trust his mistress had placed in him, reached his end and destination. But searching and looking around everywhere for the man, with months and years passing by, he found nobody, neither a one-handed man who lived in poverty, nor a beggar man who lacked a hand. He was surprised by the ignorance of the so-called wise men among the plain-dwellers, which wise men merely stared at him when he tried to explain his problem to them.

One day he came to a large town. At this point he had nearly run out of coin and provisions and had a titanic hunger in his belly. He went to the market to buy an apple or a pear. But the fruit vendor mistook him for a thief and called for the watchman, who arrested him and brought him to the town’s jail, a putrid place, one for rats and devils.

At noon the following day he was brought before a judge. This judge, like many of those who lived on the vast plain of Hoshtengu, which plain had been the Angu rebels’ stronghold during the war, hated the queen and what she stood for and had hated her all the more since it had become clear to him and everybody else that her promise of tabulating the war killings and recompensing all victims’ families had been as empty as the air she breathed. And the only thing the judge loathed more than royalty was broken promises.

Such was the judge before whom the official was brought. The judge heard the case, listened to the fruit vendor, the watchman and the official. He happened to know the fruit vendor from previous cases and knew that he was a confused, unreliable man. But because the official was a functionary from Wengti, and because the judge’s loathing was strong, and because the judge had not yet had lunch and for that reason was in an irritable mood, he accorded the accused the customary punishment for theft: he ordered his left hand cut off.

The official was dragged out into a dusty courtyard and had his hand cut off by a double-edged axe that shone like the Hoshtengu plains.

He staggered through the town’s streets. He came to a garden with fruit trees and flowers where he laid himself down belly up. He saw sitting in one of the trees a beautiful, blue-plumaged bird and felt suddenly like a gull floating stilly on a cool coastal wind. He felt like a gull afloat on a coastal wind because he remembered a story about the plain-dwellers of glittering Hoshtengu.

He remembered that there was on the plains of Hoshtengu a blue-plumaged bird which the plain-dwellers worshipped. They never killed these birds. But when a plain-dweller child reached the age of 12, they had to prove themself to the village by stealing and walking away with its egg from the nest, well-hidden and -guarded though it was.

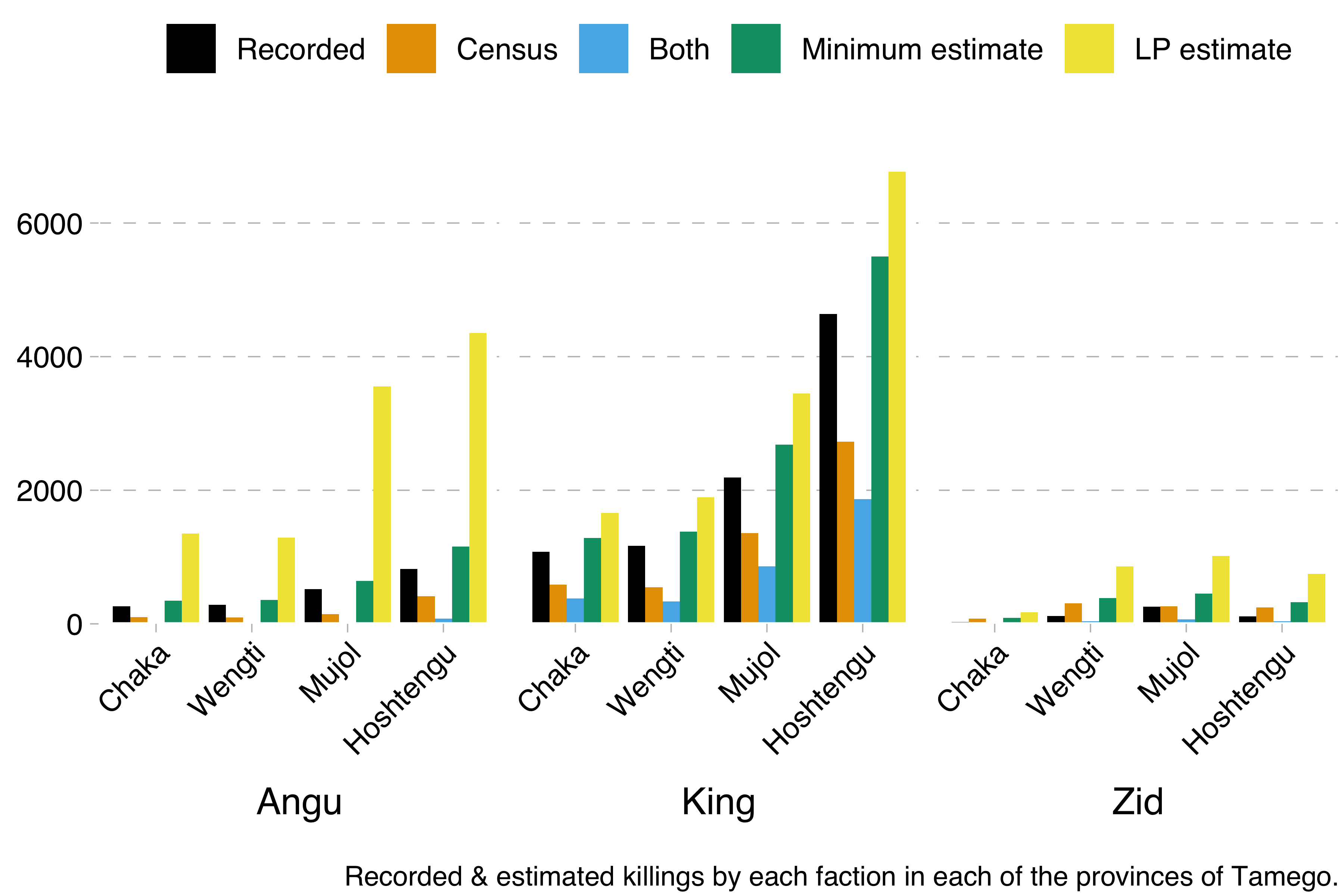

Now, it happened that these nests became more difficult to find as the years passed. This was a cause of great worry for the plain-dwellers. So they came up with a scheme to count the birds. Of course they could not see all the birds at once. So they were forced to use their cunning wits. They went to the eastern reaches of the plains where they knew the birds went to mate and play. There they chose a small section of the area, set up traps and, having caught all the birds in that area, attached sturdy bronze rings around their feet and released them again.

Then the plain-dwellers went home, but they returned the following year, again setting up their traps and again catching all the birds in a small area. This time they counted how many of those birds had bronze rings around their feet. And realising that the proportion of captured birds in the first year to the total number of birds should equal the proportion of captured and bronze-ringed birds the second year to the total number of captured birds the second year (or, put differently, that the probability of detecting a bird in the first year equalled the probability that a detected bird in the second year was marked with a bronze ring) – realising this, they were able to estimate the true population of their beloved blue-plumaged god-bird.[1]

All this the official remembered and, remembering, he rejoiced at his having found at last a method to solve all his problems. He got up and eked out a living on the dirt-ridden streets of the town, now determined to return to his queen with the answers he had sought for so long. But the wound where his hand had been had begun to rot and fester and within the month he had died a pauper, forgotten by everyone.

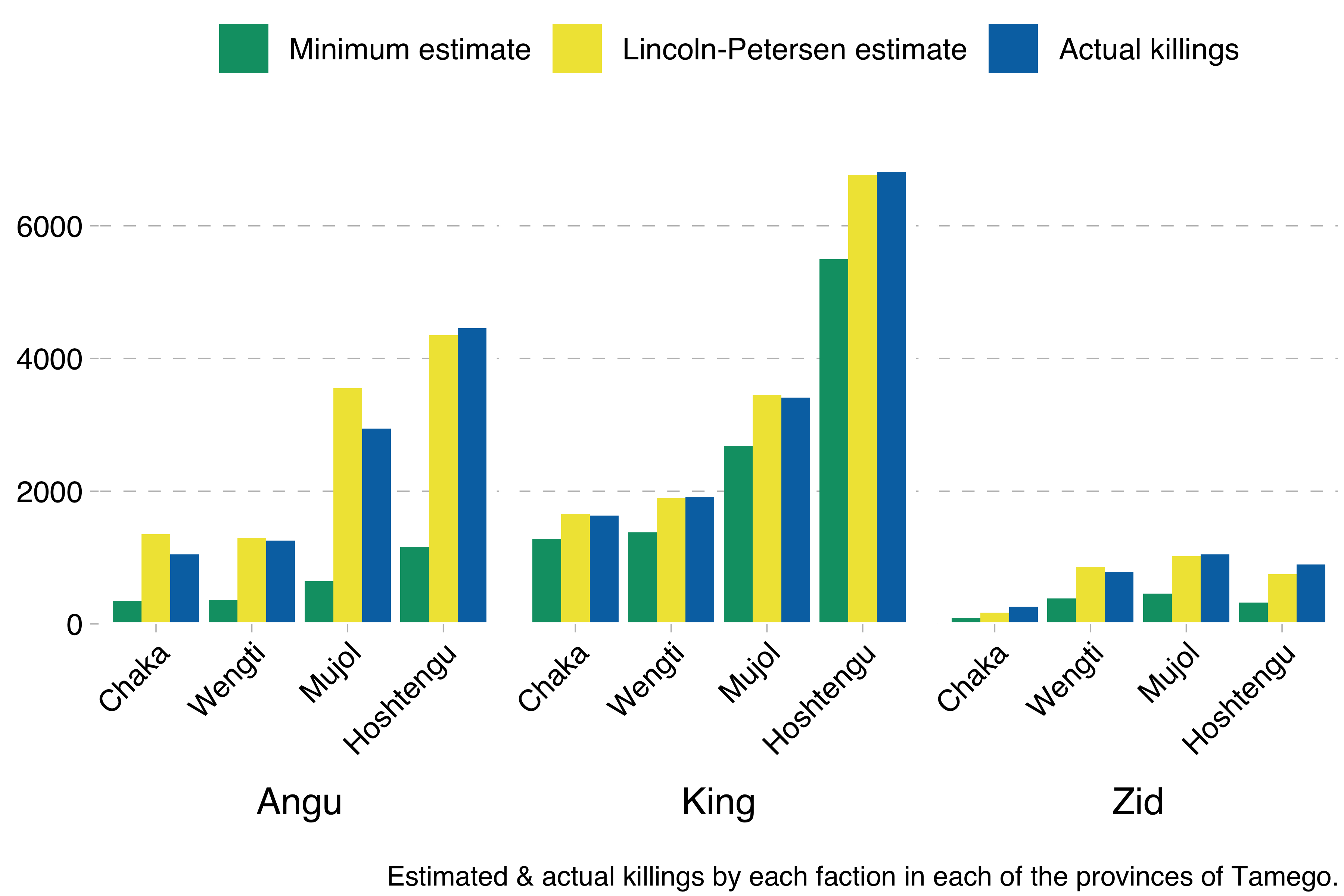

(Postscript: This was a tale about capture-recapture methods in population ecology. Specifically, the formula used by the plain-dwellers is the Lincoln-Petersen method of estimating population size based on capture-recapture data. These methods have also been used in other domains, e.g. for estimating killings in a civil war or the number of daily drug injections in a city. As you can see in the graph below, the Lincoln-Petersen estimate for the simulated Tamego data is quite accurate, though my simulations probably underestimate the measurement error we’d see in real data.)

Footnotes #

So if, for instance, there were 500 birds, and they captured and marked 100 of those, then one fifth of the population is marked. After a year has passed and the birds have mixed, they capture another 100 – this time, because the marked birds have mixed with the unmarked birds, they will find, out of those they have caught, 20 birds that are marked, because each bird has a one-in-five chance of being marked. And because

100/500 = 20/100, they can derive the bird population (500) from the other three numbers. ↩︎