This post is part of a series on theory and terminology in animal advocacy:

- Rights or Welfare for Animals?

- Possible Resolutions to the Rights/Welfare Debate in Animal Advocacy

- ➾ Dimensions of Animal Advocacy Terminology

Dimensions of Animal Advocacy Terminology

Do not rush to speak, for that is a sign of madness.[1]

– Bias of Priene, via Diogenes Laertius

All of my observations so far have led to very little in the way of conclusion. So, yes, animal advocacy underwent a period of conflict with animal welfarists on one side and animal rights abolitionists on the other, and Effective Animal Advocates (EAAs) may be able to resolve that conflict more or less satisfactorily. But what does that mean for the problem of terminology, the one that the Sentience Institute touches on when it asks whether we, “[w]hen discussing the plight of farmed animals, should […] use terms like ‘rights’ and ‘autonomy’ or ‘welfare’ and ‘suffering’”? After writing my way through this, I am sure I don’t know what terminology EAAs should adopt in such-and-such a circumstance, but I do think I have a pretty good idea of what parameters we can adjust when choosing a terminology or message.

From a pretty cursory look at the research, I gather that several attempts have been made, both by EAAs and other researchers, to understand if some message X persuades more effectively than some other message Y, but that these studies are often underpowered and/or plagued by methodological issues like lack of control groups. What’s more, usually these studies are testing whether people change their diets as a result of having seen new information, but it’s not clear that this is the most important thing to measure; in the long-term, it could for example be better to change attitudes or donation patterns (assuming for the moment that they are not too tightly coupled, in which case it’s kind of all the same). My general impression is that EAAs currently base a lot of their terminology and messaging choices on their experience in advocacy and on their having talked to a lot of people about animal ethics.

Status Quo #

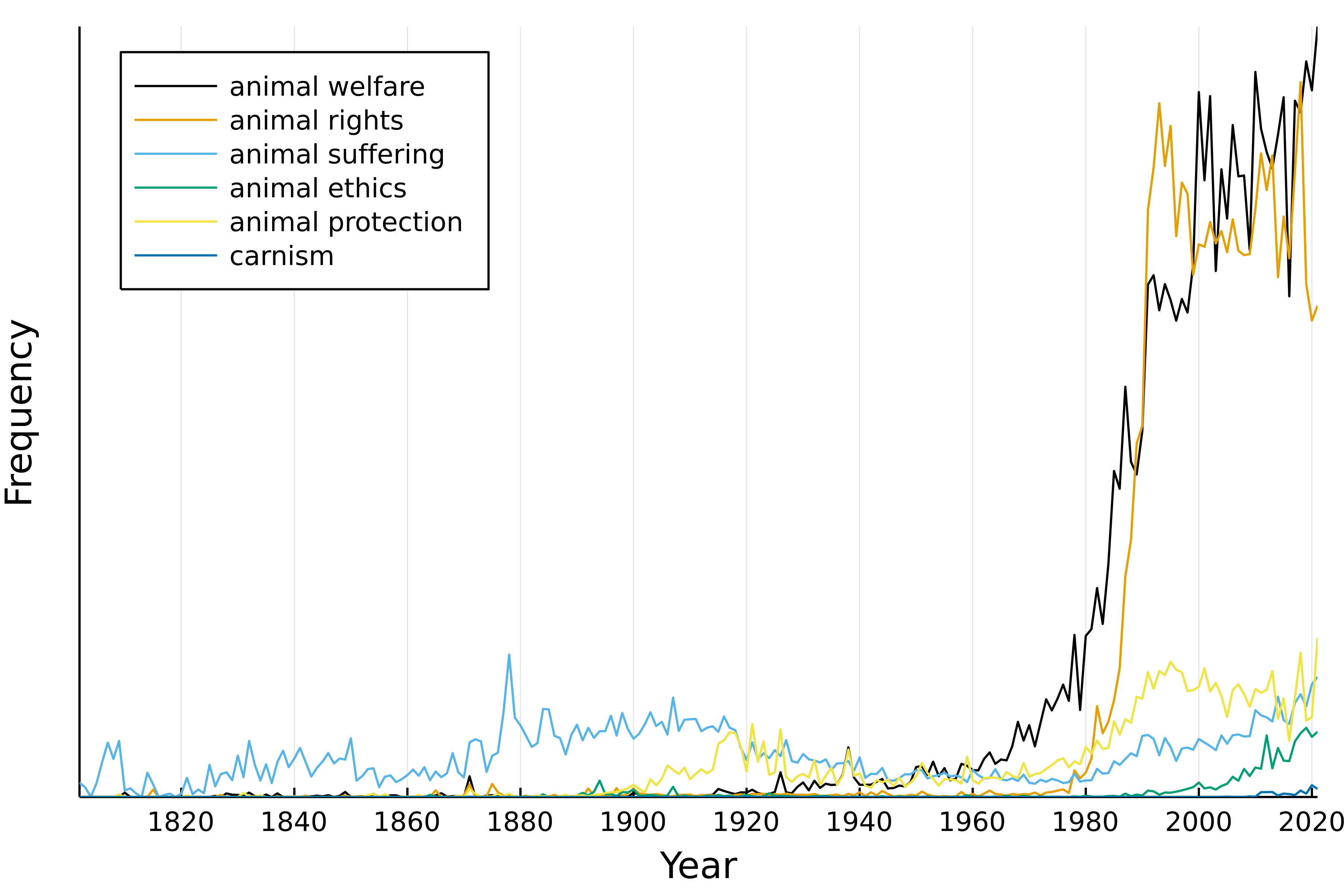

Let us quickly survey the current landscape. Here are some common overarching terms used in animal advocacy, with frequency of use on the y-axis, courtesy of Google Ngram. The plot shows “animal welfare” overtaking “animal rights” in frequency in the late 1990s. The gap has again widened significantly starting around 2015, which is not long after effective altruism (EA) got off the ground as a movement (though I think it unlikely that effective altruism is behind the recent change; EA seems far too niche).

Note however that there are likely marked regional differences, as hinted at in Google Trends. In Protestant Europe and Canada, for example, it seems that people frequently search for “animal protection”; compare with common terms like djurskydd in Swedish or Tierschutz in German, as seen for example in Djurskyddsföreningen (The Animal Protection Association) and the Deutsche Tierschutzbund (The German Animal Protection Association). The term “animal rights” seems prevalent in the Slavic world, though my wife, who is Russian, tells me that the most commonly used Russian term translates to “animal protection”, so I am not sure about this. Either way, globally, and especially in the Anglo world, it seems that “animal welfare” is now the dominant term.

Here are some words prominently displayed on the front or mission pages of various EAA organisations:

- Albert Schweitzer Foundation: animal welfare, animal suffering, animal rights (on their campaigns page), veganism

- Anima International: animal suffering, “promot[ing] progress, not just veganism”

- Animal Charity Evaluators: animal suffering, animal advocacy, anti-speciesism (on their philosophy page)

- Good Food Institute: “mitigat[ing] the environmental impact of our food system, decreas[ing] the risk of zoonotic disease, and ultimately feed[ing] more people with fewer resources” (remarkably, there is no front page mention of the word “animal” at all)

- The Humane League: animal welfare, animal suffering, “end[ing] the abuse of animals raised for food”

- Mercy for Animals: animal abuse, cruelty, respect, protection

- Sentience Institute: moral circle expansion

- Wild Animal Initiative: animal welfare, “understand[ing] and improv[ing] the lives of wild animals”

As for the relics, Williams identifies five themes in messaging by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA): “animal cruelty, suffering and sentience, necessity, exploitation, and harm to humans”.[2] Whereas PETA emphasises the cruelty of most animal use, HSUS and ASPCA talk more about unnecessary suffering and/or exploitation of sentient beings.[3]

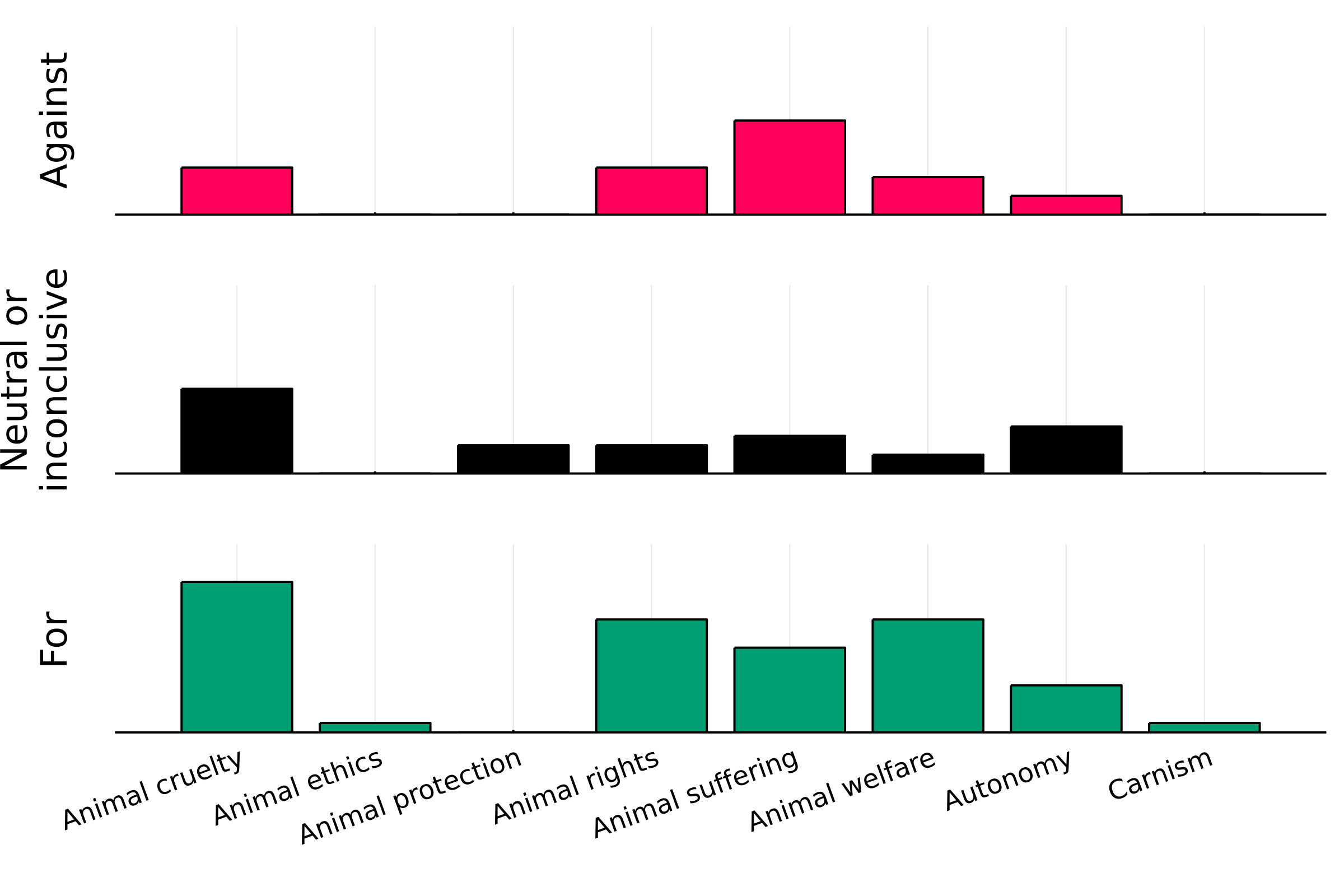

For a very rough look at which terms are used in the wild, I scraped r/changemyview, looking at the first 500 comments within the 20 all-time top voted animal ethics-related threads (of which 13 ended up containing at least one post that included at least one of the search terms). I then manually went through the comments to see if they seemed to argue against animals, for animals or if they were neutral.

This is of course a super rough proxy for what terminology people use online when discussing animal ethics, but the phrase that appeared in most comments in my sample, and used especially by people arguing for animals, was “animal cruelty” (30 comments), followed by the triad of “animal suffering” (23), “animal rights” (20) and “animal welfare” (18).

Dimensions #

What follows is a list of eight salient dimensions in animal advocacy terminology. Some of these are unipolar (they go from zero to one, so to say) and others are more or less bipolar (they go from “negative” one to “positive” one); a few may not be truly dichotomous. But hopefully they can all be useful in thinking about terminology and messaging.

Rights/Autonomy versus Welfare/Suffering #

By this, I mean essentially language appropriate to the deontological views advanced by Tom Regan and more recently Christine M. Korsgaard versus language appropriate to the utilitarian view advanced by Peter Singer.[4][5][6] I discussed this in the first post in this series.

Politically Left versus Politically Right #

This one might be a little difficult to see due to the facts that most animal advocates are and have been on the left and that the modern movement for animals is partly an outgrowth of older leftist movements. But here I mean for example talk of “justice” and “liberation” versus talk of “stewardship” and “sanctity of life”, in other words left-coded words versus right-coded words.

The most prominent animal advocate on the right today that I know of is Matthew Scully, a conservative speechwriter and journalist who often writes about animals in the National Review. In this article, for example, he compares animal advocacy with pro-life advocacy:

I first learned about the “abortion rights” cause and about the ruthlessness of industrialized farming around the same time, at the age of 13 or 14, and my reaction to both was similar: You just don’t treat life that way. Look at pictures of the victims in each case, at the thing itself, and you know that whatever problems the people involved are facing, this cannot be the answer. […] Animals have a moral dignity of their own, a point that nearly everyone, including even some people in cruel industries, will happily concede in unthreatening contexts – that is, when we’re not talking about actually doing something to protect animals and respect their dignity. […] One could note, among other venerable authorities, the Catholic Catechism’s reminder that human kindness is “owed” to animals, and that it is “contrary to human dignity to cause animals to suffer or die needlessly”. [… A] dutiful regard for animal welfare helps keep us humble, as a natural check against all of mankind’s own endless fiats, much as the duty to put the interests of children first can steer adults and entire societies away from all kinds of destructive self-indulgence.

Focus on Humans versus Focus on the the Other Animals #

So Matthew Scully argues that treating animals is humbling for humans, and that it is undignified for us not to do so. Kant famously did not regard the other animals as ends in themselves, though he thought that we shouldn’t treat them ill because doing so would be bad for human moral character.[7] This might be the thinking behind terms like “animal cruelty”, which highlight the mentality of humans who mistreat animals, or the Christian idea of stewardship, where humans are active caretakers and the other animals are merely on loan to us, so to put it, from god. Those are some human-centric reasons to go vegan or to end factory farming, but there are many others, including reducing climate change emissions, reducing the chance of new zoonoses[8], reducing antibiotics use[9] and, most commonly perhaps, improving one’s health through dietary change.

Not all of these are moral reasons, of course, and I suspect that moral reasons are stronger and more lasting than the others. I seem to remember having seen numbers on why people have become vegan, and that moral reasons were more prevalent among those who were vegan, and that health reasons were more prevalent among lapsed vegans; I have heard of the same thing anecdotally. It also makes sense: if you try veganism for health reasons, there is a chance that you don’t see any of the expected improvements, in which case you will give it up. But becoming vegan is not likely to change the moral thinking of those who did so based on their convictions.

There is a little bit of evidence that environmental or health messaging is useful in changing people’s diets. In Wolstenholme et al., people who received information about health and environmental effects of eating red and processed meat reported eating less meat than the control group.[10] Curiously, the control group was explicitly asked not to change their diets, which I think means it’s possible that any effect seen in the other groups is due to social desirability bias. And of course it is not clear whether that sort of messaging is good for retention or outcomes other than dietary change.

Links to Earlier, Human Struggles #

Previously, I quoted Gary Francione as writing that he and Tom Regan “believed that the rights movement should very clearly and very explicitly recognize the relationship between human rights and animal rights”. The abolitionist movement to which they belonged took its name from the movement to end slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries. Then there is Peter Singer, who began his seminal 1973 essay like this:

We are familiar with Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and a variety of other movements. With Women’s Liberation some thought we had come to the end of the road. Discrimination on the basis of sex, it has been said, is the last form of discrimination that is universally accepted and practised without pretence, even in those liberal circles which have long prided themselves on their freedom from racial discrimination. But one should always be wary of talking of “the last remaining form of discrimination”.[11]

And he quotes Patrick Corbett’s closing words in the final essay of Animals, Men and Morals, which book Singer is reviewing:

Let animal slavery join human slavery in the graveyard of the past.

Maybe Singer is merely channeling his hero, Jeremy Bentham:

The day may come, when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may come one day to be recognised, that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate.[12]

I think this is also implicit in the Sentience Institute’s emphasis on “moral circle expansion”. It seems like a natural parallel, and I suppose it’s telling that advocates on either side of the rights/welfare divide have connected their struggle to struggles for human rights. Those earlier movements have been largely successful and now have widespread support. I don’t know whether this is an effective messaging tactic, but there is some evidence for an association between support for animal rights and support for human rights.[13]

The other pole here would be something like the stewardship notion I mentioned earlier, which admits a large gulf between humans and the other animals. But that kind of language seems pretty rare.

Emphasis on Sentience #

In addition to connecting animal advocacy to broader human rights struggles, the Sentience Institute obviously also emphasises animal sentience. Intuitively, this seems like a good way of persuading people to treat animals better, because if animals are sentient there’s a good chance that they have moral standing. Here is one “conversion story” told by Father Frank Mann, a Catholic priest from Queens, New York:

I was riding down in this expressway in Queens and I saw a billboard and on the billboard there was a picture of a puppy – this cute little puppy – and a picture of a little piglet – this adorable little pig. It said, very simply, “Why love one” – meaning the puppy – “but eat the other?” – meaning the pig. [… I]t just hit me, and I said, “Oh my god!” I couldn’t drive any more on the expressway, I had to get off the next exit and I had to get down – this is in the evening – I drove down a quiet residential street and … I cried. I broke down crying. I was just [in] tears.[14]

He goes on to mention his later having done some reading about pigs and having learned how they have personalities, how they are intelligent and affectionate and so on. So part of his conversion was seeing farmed animals for what they were: sentient beings. In a summary of a study[15] on the social psychology of human-animal relations, Gabriel Borden writes:

In terms of what might be effective at elevating someone’s valuing of animals, the article makes the case that the more we’re able to increase empathy and understanding of a species’ intelligence, the more positive effects will be seen in the relationship with that species.

Studies show that many omnivores downplay animal sentience, intelligence or capacity for suffering in order to escape the cognitive dissonance that comes with (1) believing that we shouldn’t needlessly harm animals, etc., and (2) eating meat and other animal products.[16][17][18] That is probably why, in the West at least, meat is stripped of any trace of animal features like eyes or faces before it is packaged and sold, and also why the factory farming industry uses euphemisms like “processing” or “harvesting” or even “euthanising” for killing or slaughtering. In a press release announcing the opening of a nightmarish Mountaire Farms “processing facility”, one could read:

The plant will have the capacity to harvest 1.4 million chickens each week, all grown locally by more than 100 family farmers. […] “To be good stewards of all the assets God has entrusted to us is part of our Mountaire creed”, said Dee Ann English, Executive Vice President. “We believe our Health & Wellness centers [serving the plant’s 1,250 employees] are a big part of fulfilling that commitment since our people are our greatest asset.”

This raises a couple of interesting questions:

- To which extent does this cognitive dissonance encourage people to become vegetarian or vegan?

- To which extent does emphasising animal sentience trigger or amplify this dissonance?

If the answer to both questions is at least “moderately”, focusing on animal sentience may be an effective messaging tactic, capable of converting people in the same way that Father Mann was converted.

Moderate Asks versus Radical Asks #

Animal advocacy messaging, and come to think of it maybe all messaging, is aimed at changing people’s attitudes or behaviour, for instance getting them to donate more money, eat less meat or think animals are more worthy of moral consideration. These asks, be they explicit or implicit, can be either more moderate (“reduce your meat intake by observing Meatless Mondays”, “donate one per cent of your income”) or more radical (“go vegan”, “donate half of your income”). Brian Tomasik puts it like this:

Nick Cooney argues for moderate messages because of the foot-in-the-door effect. Others defend radical messages by citing the door-in-the-face effect and arguing that moderate messages may not translate to more radical ones. Which is right?

Tomasik points out that the factory farming industry seems to have feared HSUS more than PETA, which he suggests may be partly due to the former being more moderate than the latter. He then helpfully distinguishes between moderate/radical means and moderate/radical ends. Incrementalism is an example of advocating moderate ends, and violence is one of radical means. This distinction becomes clear when we look at Francione, an abolitionist and committed champion of veganism, who nonetheless advocates a more moderate, reconciliatory messaging:

The only way that we will end the practice of eating animals is to persuade people through productive, non-violent education and engagement (i.e., not yelling at them; confronting them in adversarial ways, etc.) that they should stop fueling the demand that keeps the animal farms and the slaughterhouses in business.[19]

This was somewhat surprising to me, but it makes sense that he should cushion his radical ends with more moderate means. Francione would probably argue that many moderate-ends asks, like larger battery cages for hens, allow corporations to look like they are doing something without really making much progress on abolishment.

When it comes to diets, the main issue is probably ease of adoption; a lot of people, and especially meat eaters, think veganism is really difficult[20]. One study by Faunalytics found that advocating for reduction in meat intake was more effective than advocating for vegetarianism. Another study found that reading an op-ed arguing for reducing meat eating (“eating less meat”, “reducetarians”) probably did not cause people to eat less meat compared to one arguing for vegetarianism (“eliminating meat”, “vegetarians”), though for some reason the group that got the reduction message were eating more meat at the start of the study (a case of regression to the mean?); both seemed more effective than the control, but the study is probably underpowered[21]; also, it was run by the Reducetarian Foundation, which presumably has an interest in seeing reducetarian messaging more effective than vegetarian messaging?[22]

I don’t have a clear idea of whether smaller asks are generally more effective than bigger asks or vice versa, and it seems to me that more research is needed. Animal Ask is one charity founded last year that is doing research on this in the context of industry and institutional change, and I look forward to seeing more of their findings.

Concrete/Local Concerns versus Abstract/Global Concerns #

In the same essay, Tomasik argues that concrete messaging is more effective than abstract messaging:

I find that personal stories help to expand people’s minds, while impersonal slogans (like “check your privilege”) have the opposite effect. I’m even a bit nervous about the slogan “speciesism” because I worry that it turns what should be a clear moral problem – suffering by individual non-human animals – into a polarizing abstraction.

Even when the websites of EA organisations surveyed above talk about animal suffering, they do it as a universal thing, where it is rarely about the suffering of some specific animal(s), but mostly the suffering of some category of animal; however, local, more specific stories, such as the Yulin Dog Meat Festival if you live in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region or Mountaire’s 1,400,000-killed-chicken-a-week plant if you live in Chatham County, North Carolina, may be much more salient. Apparently there’s also some evidence that neutering outreach is more effective when citing local euthanasia rates. Proximity is a core news value; the closer a thing happens to you, the more likely you are to care.[23]

Naturalness versus Unnaturalness #

People sometimes argue against moral or health veganism on the grounds that veganism, plant-based products and especially cultured meat is unnatural. The term “plant-based” itself emphasises the naturalness of alternative meat and dairy; “clean meat” has echoes of “clean energy”. A study by Faunalytics on attitudes to cultured meat suggests that, while addressing naturalness concerns with cultured meat was not effective at shifting people’s attitudes on it, emphasising the unnaturalness of animal meat was.

Reasons for Scepticism #

This has been a really long post and an even longer series, but I want to bring up two potential objections to this whole project before I end it. The first is that one of my premises here is that messaging is effective at all, and that terminology matters, which is not necessarily the case. Clearly some people become vegan and vegetarian, and they must have picked this up from somewhere. But it’s not necessary that they pick it up from the sorts of messages that can be put into editorials or flyers or online ads. Maybe other forces, like economic growth, alternative meat technology or youth indoctrination lie behind most dietary trends, for example, and not persuasion.

The other reason to be skeptical is the possibility that the sort of rhetoric that has drawn in animal advocates so far won’t necessarily work for the remaining 90-something per cent of the population; those who have been convinced already may be especially sensitive or empathic by nature. Vegans, vegetarians and animal advocates are strongly self-selected groups with significant differences from the rest of the population, so we should be wary of generalising from their conversion stories.

That said, EAA organisations have had some pretty impressive results so far, and it seems likely that effective messaging has been a part of that; I would like to think that, if it were not effective, advocates would have noticed and self-corrected by now. In general, there is a dearth of solid research on animal advocacy messaging, mainly because doing that sort of research is really hard, and I suspect that the best picture can be gotten from doing advocacy and talking with people who have a lot of experience in it, of whom I am unfortunately not one.

Footnotes #

Laertius, D., Mensch, P. & Miller, J. (2018). Lives of the eminent philosophers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Williams, C. (2012). The framing of animal cruelty by animal advocacy organizations. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

Regan, T. (2004). The case for animal rights. Univ of California Press. ↩︎

Korsgaard, C. M. (2018). Fellow creatures: Our obligations to the other animals. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Singer, P. (1995). Animal liberation. Random House. ↩︎

Korsgaard, C. M. (2018). Fellow creatures: Our obligations to the other animals. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Anomaly, J. (2015). What’s wrong with factory farming?. Public Health Ethics, 8(3), 246-254. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

Wolstenholme, E., Poortinga, W., & Whitmarsh, L. (2020). Two Birds, One Stone: The Effectiveness of Health and Environmental Messages to Reduce Meat Consumption and Encourage Pro-environmental Behavioral Spillover. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 2596. ↩︎

Singer, P. (1973). Animal liberation. In Animal rights (pp. 7-18). Palgrave Macmillan, London. ↩︎

Bentham, J. (1996). The collected works of Jeremy Bentham: An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press. ↩︎

Park, Y. S., & Valentino, B. (2019). Animals are people too: explaining variation in respect for animal rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 41(1), 39-65. ↩︎

See this video. ↩︎

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Loughnan, S., & Amiot, C. E. (2019). Rethinking human-animal relations: The critical role of social psychology. ↩︎

Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., & Bastian, B. (2010). The role of meat consumption in the denial of moral status and mind to meat animals. Appetite, 55(1), 156-159. ↩︎

Bastian, B., Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., & Radke, H. R. (2012). Don’t mind meat? The denial of mind to animals used for human consumption. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(2), 247-256. ↩︎

Rothgerber, H. (2014). Efforts to overcome vegetarian-induced dissonance among meat eaters. Appetite, 79, 32-41. ↩︎

Francione, “Animal Activists Get it Wrong: Farmers Are Not the Problem”. ↩︎

Bryant, C. J. (2019). We can’t keep meating like this: Attitudes towards vegetarian and vegan diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability, 11(23), 6844. ↩︎

Also, Jesse Clifton comments that, due to the statistical significance filter and to social desirability bias, the figures in the study should be upper bounds. ↩︎

Sparkman, G., Macdonald, B. N., Caldwell, K. D., Kateman, B., & Boese, G. D. (2021). Cut back or give it up? The effectiveness of reduce and eliminate appeals and dynamic norm messaging to curb meat consumption. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 75, 101592. ↩︎

Note however that I am not suggesting that proximity or familiarity should determine moral focus, I only mean to say that it can make an issue more salient, if that is desirable. ↩︎