What Made World of Warcraft’s Environments so Compelling?

I have my own way of assessing the worth of a book – not just a so-called work of literature but any sort of book or, for that matter, any piece of music or any so-called work of art. I could say in simple terms that I judge the worth of a book according to the length of time during which the book stays in my mind […]

– Gerald Murnane (2021, 9)

Like many people of my age and place, much of the nostalgia that I feel is rooted in virtual worlds – in the worlds of the video games of my youth. The foremost of those was probably World of Warcraft, which encompassed forests, mountains, farmlands, jungles, deserts, plains, swamps, highlands, badlands and more. It has been something like a decade and a half since I last played it, but I still occasionally find myself thinking back fondly, not to the painful day-to-day grind and the constant striving, but to the (far more detached and pure) exploring and absorbing of it.

To me, the landscapes in Warcraft were really compelling, by which I mean that they powerfully evoked interest and longing.[1] Why? What gave them their allure? Remembering as always the nebulous nature of questions like these, and making no claim to completeness or certainty, I will nevertheless try to sketch an answer.

Now, you have every right to protest that this sort of thing is entirely subjective. I have written about this problem before. It is a thorny issue, but even if there is no objective ground for these judgments, there are still tendencies in people’s judgments (people generally value A Song of Ice and Fire over The Sword of Truth, say), and these tendencies are sometimes correlated with objective features of the things being valued (for example, the more valued fantasy novels tend to have fewer evil chickens[2]). So I still assert the right (and think it can be fruitful) to speculate about this.

Summary #

To answer the titular question, I make some shallow research and come up with eight candidate features: naturalness, openness, colourfulness, beauty, coherence, complexity, legibility and mystery. I score 15 video games on each of these as well as “compellingness” (the outcome variable). I then make a (statistically questionable) regression analysis and find that the features most associated with how compelling a role-playing-game-like’s environments are are naturalness, mystery and complexity (variety/diversity). My confidence in these results is low (25% that the ordering is more or less correct for people on average) but as an exploratory study it seems all right.

Candidate Features of Compelling Environments #

The environments of World of Warcraft aren’t that different from natural landscapes. They probably activate many of the same synapses. Maybe research on why humans find natural landscapes beautiful can point us in the right direction?

(I’ll limit this discussion to the visible, though sound, music, story and gameplay are likely important too.)

Obvious Stuff #

The first thing that springs to mind is probably the old explanation from evolutionary psychology: roughly speaking, our ancestors found certain landscapes more hospitable or habitable, as a result of which it was adaptive for us to find such landscapes pleasant or beautiful. In the literature, this is called habitat theory, and it seems related to what E. O. Wilson called biophilia (Wilson 1984).

The biophilia theory of natural appreciation posits this. We humans are still evolving, but the vast majority of our evolutionary history took place in nature. As a result, the brain has evolved to reward certain adaptive behaviour, and sometimes this behaviour is associated with certain environments (Ulrich 1993). For instance, it might have been adaptive for us to enjoy being in places that offer ample food, drink and safety (Ulrich 1993). More specifically, maybe we like plant life because it offered food (both in the form of edible plants and grazing animals), lakes and rivers because they provided us with drinking water and open landscapes and high vantage points because they allowed us to spot dangers and avoid getting lost. (This is similar to people’s intense fear and dislike of snakes and spiders, which must have evolved due to their poisonous nature; Ulrich 1993.)

Biophilia seems plausible enough to me, but Roger Ulrich, one of its main proponents, talks about how the African savanna was so good for us, and how it was the scene for much of our evolutionary history, and how we therefore enjoy its “parklike properties such as spatial openness, scattered trees […] and relatively uniform grassy surfaces” (Ulrich 1993). He compares it to inhospitable environments like deserts and rain forests, but personally I find deserts and rain forests quite beautiful, and I’m not too enamoured with savannas. That said, I have never set foot in a desert and I’ve never seen a real rain forest with my own eyes, and Ulrich mentions several studies indicating that people generally do prefer savannas.

Far from all environments in World of Warcraft were benign. Many of them seemed quite dangerous. Steep cliff faces, treacherous swamps, thick snow, inhospitable deserts … But there is another vein of research that is not dissimilar from biophilia. Apparently – and who would have thought – people prefer landscapes that don’t have any traces of humans in them (Hodgson and Thayer 1980; Ode et al. 2009). This property is called naturalness and it seems really salient to me. The poets have always praised natural beauty, “which gives even the most insensitive people at least a fleeting sense of aesthetic pleasure” (Schopenhauer et al. 2010, 225). There is something about treading untrod ground. This will be my first candidate feature.

My second candidate feature is openness, which was mentioned in relation to biophilia. This expresses the difference between being in a small glade in a forest and standing on a summit looking out over a sea of treetops. There is some evidence that, in eye-tracking experiments, people spend more time exploring open landscapes than enclosed ones (Dupont, Antrop, and Eetvelde 2013). And people, always and everywhere, seek out viewpoints, panoramas and observatories for the sceneries they offer.

My third candidate feature is colourfulness, or vibrancy, or saturation. World of Warcraft is pretty colourful – maybe that makes it more compelling? Though my intuition here is that, while colour is important, colourfulness probably isn’t, it is a possibility.

My fourth candidate feature is plain beauty. I’m including this as a sort of control group for the experiment I will run.

Information Processing Theory #

Then there is this whole thing, developed by Rachael and Stephen Kaplan in the 1980s, called information processing theory. The idea here is that “environments that provide increased opportunities for gathering or discovering information allow for improved living conditions including heightened safety” (Dosen and Ostwald 2016). A merit of this theory is that it takes seriously the fact that experiencing a landscape is an activity, where we continuously search, move around and notice new things. It rests on four pillars:

- Coherence is the property of structure, order and harmony – think symmetry and repeating elements, textures, patterns and so on – how easy is the landscape to understand? An empty steppe is more coherent than a busy rainforest.

- Complexity is the property of information density – think variety and diversity – how well does the landscape keep your interest? A mountainous landscape with a mixture of rock, woods, lakes and meadows is more complex than a featureless desert.

- Legibility is the property of information access – how obvious is it how to access new information in the landscape, and can one explore it without getting lost? A meadow with a path running through it is more legible than a dense rainforest.

- Mystery is the property of containing as yet undiscovered information – what promise does the landscape hold? A misty forest is more mysterious than a featureless desert.

There is some evidence supporting the information processing theory. For example, Kaymaz (2012) writes that “scenes with large expanses of undifferentiated land covers, dense vegetation and obstructed views are low in preference”. Those would all be examples where there is little information, or where information is difficult to access. And I can’t find the source now, but I also seem to remember reading that subjects prefer landscapes with paths leading into them, in other words landscapes that are legible.

Maybe some case studies will serve.

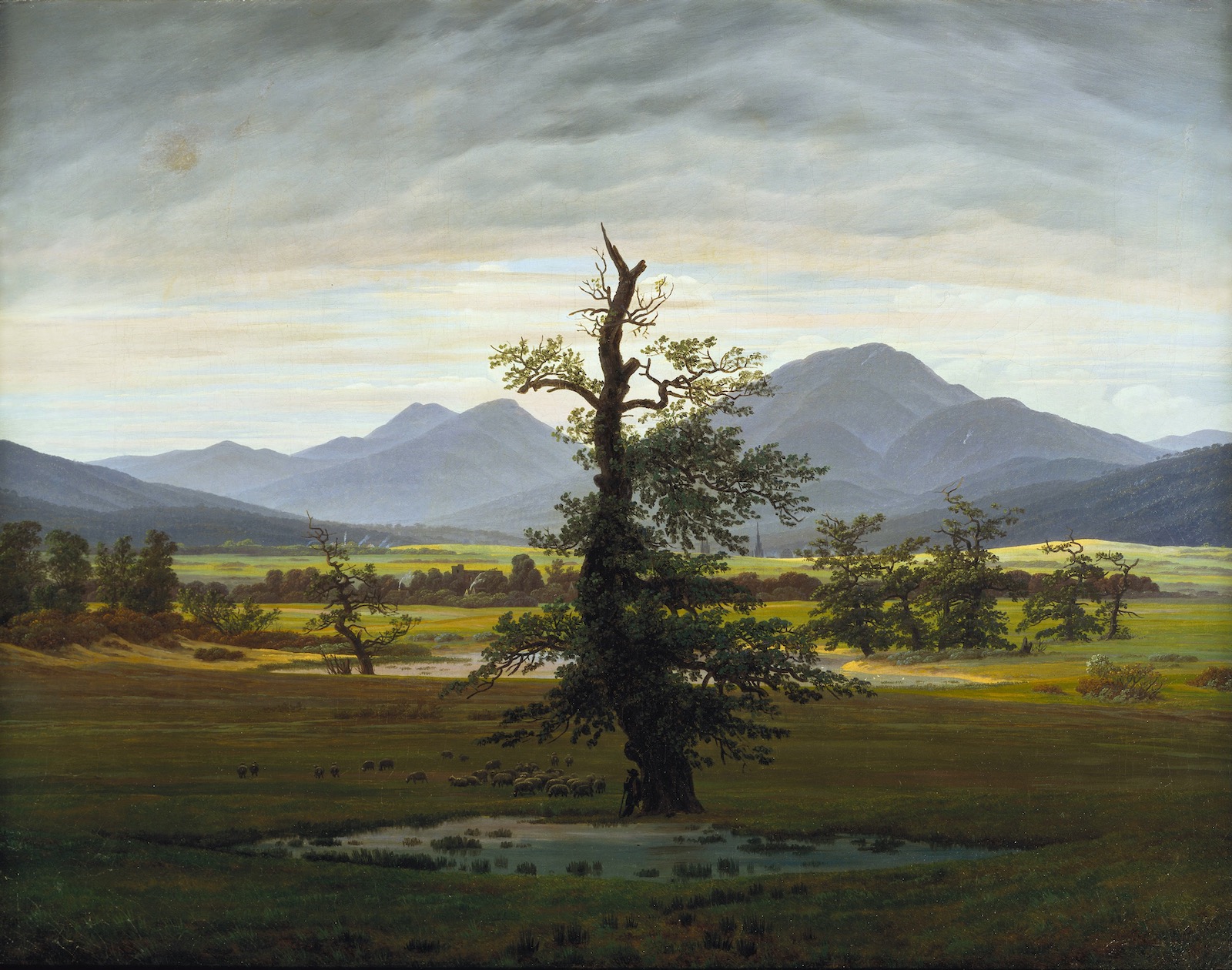

This is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich. It is, in my judgment, coherent (it is, being a painting and a masterwork, extremely well composed and balanced), complex (there are trees, bushes, meadows, ponds, mountains, clouds) and fairly mysterious (what lies behind the trees and beyond the mountains?) but not very legible (there is no clear path, though neither does it seem easy to get lost).

Here is a different painting, by John Constable. This one, unlike the previous, does, with the road on the right and the bridge on the left, and with the generally familiar and tamed features, seem legible. It also seems coherent (it is balanced and harmonious) and complex (there are many little things going on) but not containing a whole lot of mystery (except perhaps to ask us what happens behind the trees and in the pinkish-orange house).

A third painting, Camille Corot. This scene is very legible (there’s a path taking us deeper into the environment) and very mysterious (lots of little hiding-places, not to mention a whole village, to explore). It seems coherent too, but not very complex (there are the houses, the path, yellow grass, green foliage and blue skies and not much else).

I know what you’re thinking right now. How legible is a steppe, which seems easy to explore and equally easy to get lost in? What is harmony, structure, order? This all seems mortally subjective, doesn’t it? I agree but, given that I don’t have a solution for this, will simply note the difficulty and power on.

Exploratory Evaluation of Said Candidate Features #

Although what I’m about to do now is sure to cause a chorus of grinding teeth to swell up among the statistically literate – and consider this a warning, and judge the results accordingly – I think it will serve as a first exploration, and it has, if nothing else, at least clarified to me what I think is most salient.

So armed with this set of candidate features – these eight properties of environments that may or may not cause them to be more compelling on average – I drew up a list of 15 games that I used to play in my youth, all more or less role-playing games that share some features with Warcraft, and scored each of them on each of these dimensions as well as the outcome variable, compellingness. I gave them scores from one to three, where one was “noticeably below average”, two “about average” and three “noticeably above average”. I then went over the resulting table and calibrated the scores across all the rows and columns as best I could.

So Warcraft, for example, I judged to be above average in compellingness (obviously) and naturalness (to be sure, there are other people there, but the overwhelming impression is one of large, natural landscapes) but only around average in beauty. Another game I included, Deus Ex, was, for example, below average in complexity (pretty sparse environments) and naturalness (many indoor or urban environments) but around average in openness (you do get a sense of distance at times but hardly on the scale of Warcraft and similar games).

What I did next was simply to calculate the correlations between the candidate features and compellingness.[3] That produced the following ranking:

- Naturalness[4] (r = 0.83)

- Mystery (r = 0.63)

- Complexity (r = 0.54)

- Openness (r = 0.33)

- Legibility (r = 0.16)

- Coherence[5] (r = 0.03)

- Beauty (r = -0.03)

- Colourfulness (r = -0.03)

I cannot stress enough how unscientific this is. The sample is small. The statistical analysis is naive. There were many degrees of freedom in the way I set up the experiment and in the scores I assigned each game. The scores are based on my judgment and probably don’t generalise. Correlation does not imply causation. Et cetera. In other words, it is exploratory.

But enough throat-clearing. The results did kind of fit my priors. The two features that I added without evidence from the literature, beauty and colourfulness, were both uncorrelated with the outcome variable, whereas the most correlated features were recurring themes in the literature. And I myself have always been drawn to natural landscapes and have always loved mystery and the promise of things to come. That is why I prefer old-growth forests over parks, and why I sometimes derive more pleasure from fantasising about a book’s contents than I do from actually reading it.

Conclusion #

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote, in The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, that he sought out nature in order to escape and forget:

I climb the rocks and mountains, descend into the valleys and woods, to withdraw myself as much as possible from the remembrance of man, and the pursuits of the wicked. It appears to me, that when shaded by a forest I am forgotten, free and peaceful as though I had no longer any enemies, or that the leaves shield me as much from their attempts, as they put them from my remembrance; supposing, in my folly, that as I no longer think of them, they no longer think of me; and I find so great a pleasure in this illusion, that I should give into it entirely, did not my situation, weakness, and wants, forbid me.[6]

The first time I read this, I thought, “Things could not be any more different for me. My interest in nature has nothing to do with what I’m leaving behind, and everything to do with what I might find. There is surely a vast gulf between people like Rousseau and people like me.” But then I realised that the reason that Rousseau found a refuge in nature might have had something to do with all the things that make nature compelling for me, too, and that the difference between Rousseau and myself did not lie in how nature produced its effect in us, but in what that effect meant for us.

References #

Footnotes #

I say were because I haven’t played the game in a very long time, but I should really say that I remember them as having been that way. Quite possibly they were just the backdrop for some pleasant experiences I had and the memory of them is mingled with the pleasantness such that I have retrofitted this assessment of compellingness. Who knows? Least of all I. I will sort of equivocate here between they way things were and the way I think about them now, confident that you, dear reader, will be gracious and understanding and make the right inferences anyway. ↩︎

I refer, of course, to Terry Goodkind, who once wrote this: “Hissing, hackles lifting, the chicken’s head rose. Kahlan pulled back. Its claws digging into stiff dead flesh, the chicken slowly turned to face her. It cocked its head, making its comb flop, its wattles sway. ‘Shoo’, Kahlan heard herself whisper. […] The bird let out a slow chicken cackle. It sounded like a chicken, but in her heart she knew it wasn’t. In that instant, she completely understood the concept of a chicken that was not a chicken. This looked like a chicken, like most of the Mud People’s chickens. But this was no chicken. This was evil manifest.” ↩︎

There is at least one possible confounding variable here: the time I spent playing each game. That is, maybe I remember some types of games, like massively multiplayer online role-playing games, say, as being more compelling, not because of their environments, but because I spent more time playing them. At first, I wanted to condition on time spent in my analysis. But then I realised that the causality could just as well run the other way – that perhaps I played some games more because they had compelling environments – in which case conditioning could mask a real effect. So I decided against it. For what it’s worth, there was indeed a weak correlation between time spent and compellingness, but conditioning on time spent would not have changed the results much at all. ↩︎

I actually also encoded a feature that was meant to track how much human, animal and plant life an environment contained, but this ended up being really correlated with naturalness (and similarly correlated with compellingness) so I chose not to include it in the results. ↩︎

I found coherence the most difficult property to judge. ↩︎

This is from an anonymous translation published in 1796, which you can read in full here. ↩︎