This post is part of a series on Marilynne Robinson's views on economics and nuclear safety:

- Marilynne Robinson's Quest for Truth

- ➾ Nuclear Decay

Nuclear Decay

There is no group in history I admire more than the abolitionists, but from their example I conclude that there are two questions we must always ask ourselves – what do we choose not to know, and what do we fail to anticipate? (Robinson 1998)

– Marilynne Robinson

I have not read Marilynne Robinson’s 1989 book Mother Country, but I understand that it is a critique of nuclear power and the British government which produces it, focusing especially on the Sellafield nuclear site, which, in Robinson’s words, has been “incalculably destructive of the public health” (Robinson 1989, 4). Sellafield was originally used to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons but has since then been used to generate electricity, reprocess fuel and store nuclear waste among other things. One of the key claims that Robinson makes is that Sellafield’s activities have caused leukemia in children of the surrounding communities. (She makes several other criticisms too, for example to do with corruption, but I won’t discuss those in this post.) Here she is pillorying two contemporary American news stories:

Both mention alarm caused by leukemia cases too few to be statistically reliable, repeating a bitterly disputed claim by the British government; that is, by the plant’s owners and operators. In fact, one child in sixty dies of cancer in the village nearest the plant, and rates in other villages in the region are comparable. To find ambiguous these high rates of a radiation-induced illness in a radioactive environment seems to me willful at best. (Robinson 1989, 16)

But the evidence is ambiguous. There was certainly a cluster of childhood leukemia cases near Sellafield in the 1980s (Kendall et al. 2016). The radiation received from the site has been estimated to be lower in magnitude than natural background radiation, and “much too small, by a factor of at least 100, to account for the excess cases of childhood leukemia” (Wakeford, Little, and Kendall 2010). An analysis that spanned the period from 1950 to 2006 found no increased risk in people living near the site – which has been active since 1947 – before or after the 1980s cluster (Bunch et al. 2014). One proposed causal path was that irradiation of workers at the Sellafield site would have caused leukemia in their children, but this seems not to have been the case (Tawn 1995; Wakeford 2013), as is true also for the effect of radiotherapy (Boice et al. 2003). Direct exposure may still have played a role (Wakeford 2013). But to me it seems more likely that this was just chance – leukemia incidence is heterogeneous, such that clusters form at various times and various places by chance alone, only of course it is those that happen near nuclear sites that are written about and therefore noticed and remembered.[1] (An alternative theory is that the cluster was the result of virus spread due to population mixture (Kendall et al. 2016).)

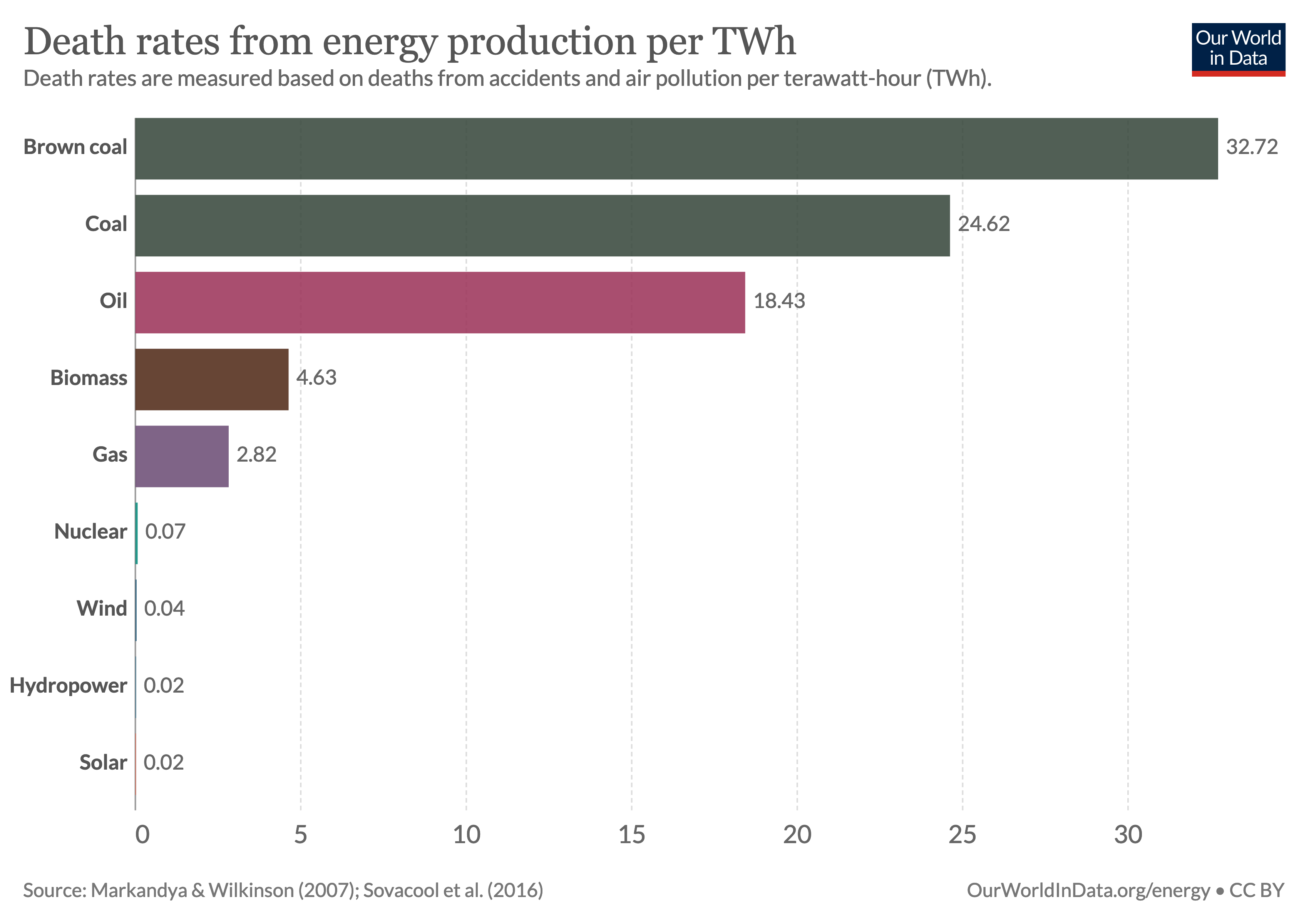

Humankind needs a certain amount of energy in order to thrive. You can argue that this necessary amount is far lower than what we currently use, but surely it is a significant amount still. Say, for the sake of argument, that we need 100,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year (right now we produce something like 170,000 TWh yearly). This energy needs to come from somewhere. But in production there are accidents, and there is pollution. Estimates suggest that, if we were to produce all of that energy – and let’s assume, again for the sake of argument, that all these energy sources scale without difficulty – with hydro or solar power, then 2,000 people would die every year, or with wind power, 4,000 people dead, or with nuclear power, 7,000 people; but if we had produced all of that energy with natural gas instead, nearly 300,000 people would die, or with biomass, nearly 500,000, or with oil, nearly 2,000,000, but over 3,000,000 people would have died every year had we produced the 100,000 TWh with brown coal (Ritchie and Roser 2020).

If you prefer graphs, here is one showing average fatalities per TWh of energy produced (Ritchie and Roser 2020):

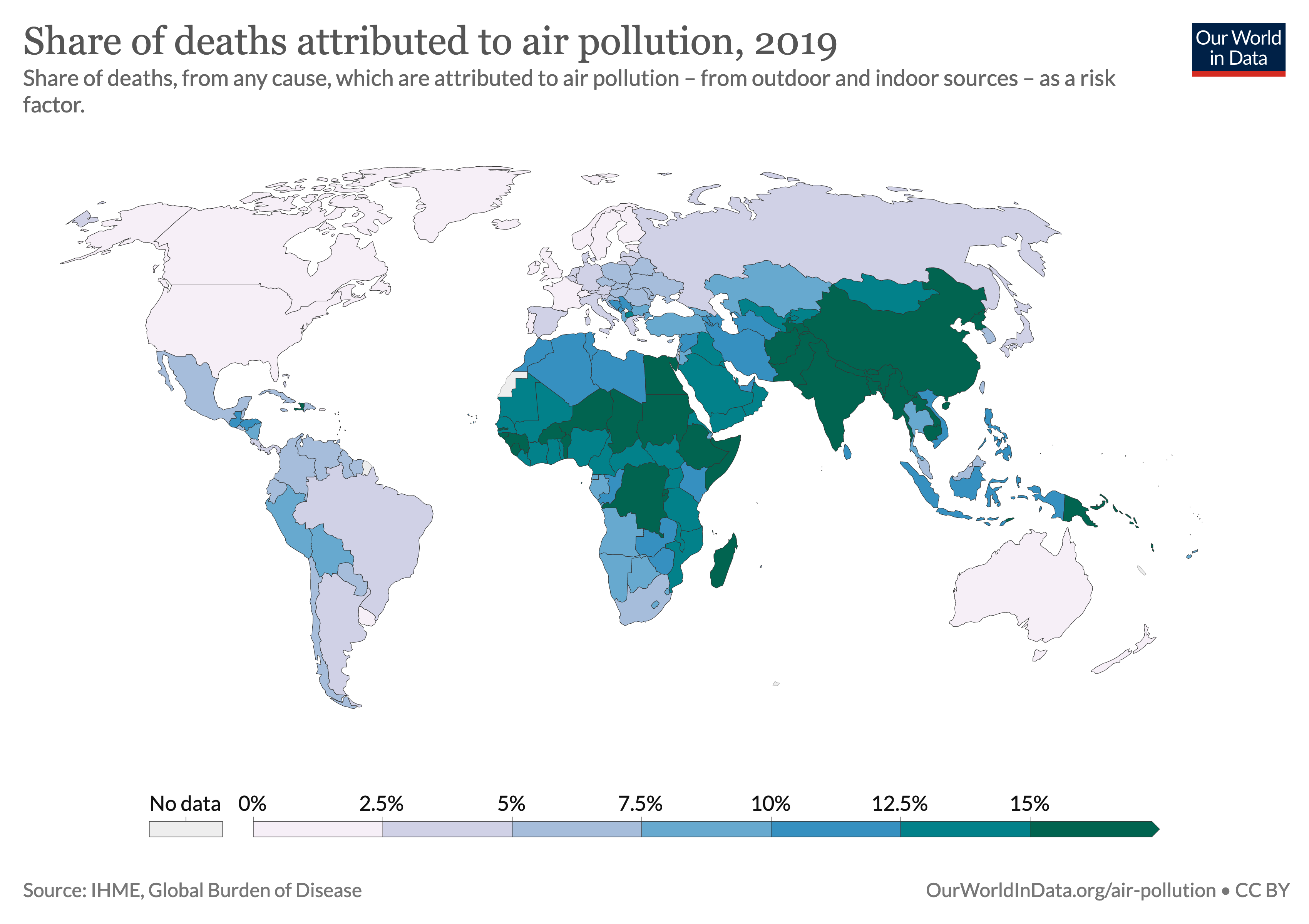

The reason that energy sources like coal and oil are harmful is that they pollute the air (Ritchie and Roser 2020). Air pollution is a major cause of death, mainly in Africa and Asia (Ritchie and Roser 2020):

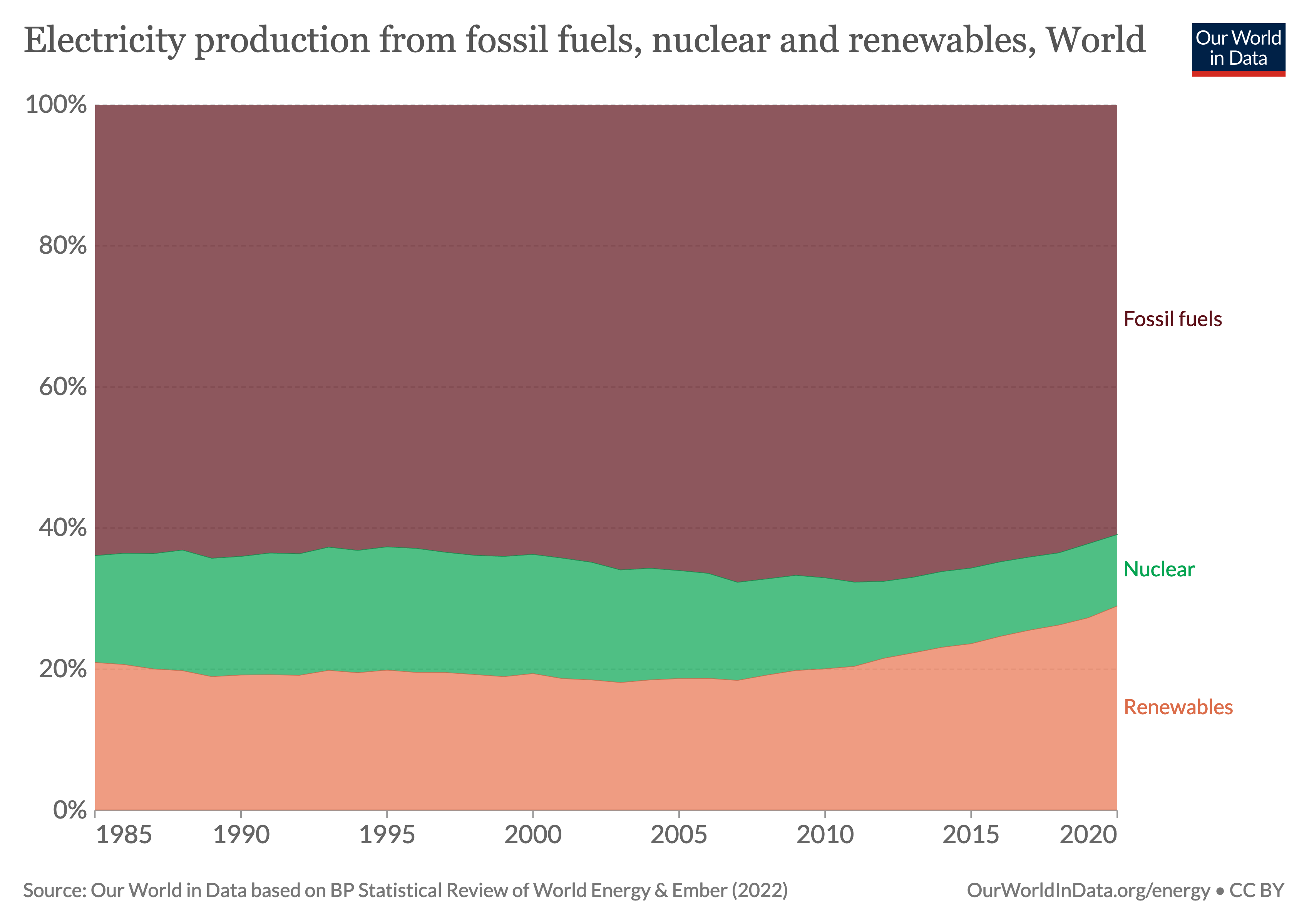

Objection: The first graph shows that nuclear energy is more harmful than renewables like wind, solar and hydropower. Instead of ramping up nuclear energy production, we should replace coal and oil with renewables. Reply: We are already straining to increase production of renewables, but it will take a long time until they can replace coal, oil and gas completely. These days, nearly 80% of our energy comes from oil, coal or gas (Ritchie and Roser 2020). Renewables are safe and clean, but today they produce only something like 11% of energy (Ritchie and Roser 2020). Imagine, looking at this graph of electricity production by energy source, if we had ramped up nuclear in the 2000s instead of ramping down, how much less reliant on fossil fuels we would have been (Ritchie and Roser 2020):

That is, nuclear energy, far from being a public health hazard, has actually saved (and can still save) lives, by replacing far more dangerous energy sources like coal and gas (Ritchie and Roser 2020). Apart from safety considerations, nuclear also emits far less greenhouse gas than does coal, oil, natural gas or even hydropower (Ritchie and Roser 2020).

Objection: Radioactive contamination might have all sorts of bad effects that don’t show up immediately in mortality statistics. Radioactive waste needs to be stored somewhere for thousands of years (if it is not to be discharged into the sea as at Sellafield). Reply: I think nuclear waste storage is a real problem that is not dealt with well enough today. But part of the reason it’s not dealt with well enough is people’s skewed perception of nuclear energy safety, which causes them to protest any proposed storage site as soon as it’s being considered.[2]

I realise that the spectre of Chernobyl has settled deep in our souls – I’m no exception – and that for this reason and others nuclear disasters are much more salient than all those deaths caused by air pollution. But what do we really care about? Reducing our fear of death or reducing the number of actual people actually dying? If a friend of yours were convinced that they are dying from 5G radiation, what do you do? Do you help them move into a cabin in the wilderness or do you try to help them see that their reasoning is all wrong? I don’t need to say which option is healthier because the answer is plain.

This is not just a matter of flawed arithmetic. This is Robinson, who has taken upon herself the task of defending the wronged and downtrodden, utterly letting down all those whose lives have been saved, and those whose lives could have been saved, from the production of dirty fossil fuels. There is a trade-off here, and something prevents her from seeing that she is arguing for the wrong side – the side that would have us see more people dead.

Am I being unfair criticising something that someone wrote over 30 years ago? Maybe Robinson has arrived at a more nuanced position since then, or at least acknowledged some or another flaw in the original argument? But no. Here is what she said about it in a 2008 interview:

If I could only have written one book, that would have been the book. […] [I]f I had not written that book, I would not have been able to live with myself. I would have felt that I was doing what we are all doing, which dooms the world. […] I was angry when I wrote that book. Nothing has happened to make me feel otherwise about the issues I raised in it. Sellafield is only larger now.

She has also remarked:

The world’s most favored public, our own, is educated thoroughly and badly, starved of information, and flattered as to its own importance. While it is made incompetent in the use of the power it has. There is no agora, where issues are really sorted out on their merits and decisions are made which, at best and worst, give permission to political leaders to carry out policies the public has approved. This model assumes information of a quality that is by no means readily available to us. It assumes a reasonableness and objectivity which allow information to be taken in and assimilated to our understanding, and in this we are also thoroughly deficient.

References #

Footnotes #

People, including children, have died due to radiation from nuclear sites. This is tragic, but so are deaths caused by other energy sources. It is not a choice between some deaths and no deaths, but between some deaths and many more deaths from coal, oil and natural gas. ↩︎

It’s also not clear to me how bad radioactive exposure is for the environment. I mean, it’s definitely bad on some level. If humans can get cancer from exposure, presumably animals can, too. But plant and animal life seems to be doing pretty well around Chernobyl nowadays (Deryabina et al. 2015). Of course it’s possible for contaminated plants and animals to travel up the food chain and reach humans that way, but that should show up in mortality statistics. ↩︎