This post is part of a series on Marilynne Robinson's views on economics and nuclear safety:

- ➾ Marilynne Robinson's Quest for Truth

- Nuclear Decay

Marilynne Robinson’s Quest for Truth

“What led you to start writing essays?” she was asked. And the famous author Marilynne Robinson answered:

To change my own mind. I try to create a new vocabulary or terrain for myself, so that I open out – I always think of the Dutch claiming land from the sea – or open up something that would have been closed to me before. That’s the point and the pleasure of it. I continuously scrutinize my own thinking. I write something and think, How do I know that that’s true?

Having beliefs that are true is important because it helps us achieve our goals. I think Marilynne Robinson’s goals on these topics are not that different from mine – I think she wants sentient life to flourish, suffering to disappear, prosperity, world peace, spiritual growth and all that stuff. To achieve these goals, the mindset she describes – what Julia Galef calls a scout mindset – is extremely useful. Unfortunately she fails to live up to her own standard.

Summary #

Marilynne Robinson argues that cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is bad. I argue that it is flawed, but not in the way that she thinks, and that the alternative to rigorous decision analysis is not no analysis, but bad analysis. Marilynne Robinson also argues that the current global economic order means “the poor will remain poor”. I argue that the reductions we’ve seen in poverty globally, which she dismisses, are large and important.

On Cost-Benefit Analysis #

In an essay for the New York Review of Books titled What Kind of Country Do We Want?, Marilynne Robinson argues that:

- The state of things in America is bad. Life expectancies are down, suicides are up, optimism is gone and there is a “decline in hope and purpose” which amounts to a “crisis of civilization”. America is the wealthiest nation ever to exist, but still budget cuts are made in education, infrastructure, national parks and the postal service.

- The reason that things are bad is the profit motive. For example, low-income workers have no hope for fair compensation. That is because companies optimise for profit at the expense of everything else, for example moving production to countries like China (as Robinson puts it, “American workers have been competing against expatriated American capital”).

- We have internalised the profit motive in the form of CBA. This way of thinking kills altruism and enshrines self-interest.

I think there is some truth to (1) and (2), but I think that (3) is mistaken.

Robinson writes:

In recent decades, […] a particular economics has become a Theory of Everything, subordinating all other considerations to some form of cost-benefit analysis that silently insinuates special definitions of both cost and benefit. If neither of these is precisely monetizable – calories might have to stand in for currency in primordial transactions – personal advantage, again subject to a highly special definition, is seen as the one thing at stake in human relations. The profit motive has been implanted in our deepest history as a species, in our very DNA.

Then, having enumerated all the injustices of which the American government is guilty, she locates the source of these in CBA:

The theory that supports all this is taught in the universities. Its terminology is economic but its influence is broadly felt across disciplines because it is in fact an anthropology, a theory of human nature and motivation. It comes down to the idea that the profit motive applies in literally every circumstance, inevitably, because it is genetic in its origins and its operations. […] Behind every act or choice is a cost-benefit analysis engaged in subrationally. This is to say that thinking itself is the product of this constant appraisal of circumstance, which is prior to thinking, therefore not subject to culture, moral scruples, and so on, which are merely a scheme of evolution to hide this one universal intention from the billions of us who, in our endless diversity, make up the human species. […] Because there is only one motive – to realize a maximum of benefit at a minimum of cost – those who do not flourish are losers in an invidious, Darwinian sense. Winners are exempt from moral or ethical scrutiny since advance of any sort is the good to be valued. […] The cult of cost/benefit – of the profit motive made granular, cellular – not only trivializes but also attacks whatever resists its terms.

In a subsequent letter to the editor, the economist Donald Wittman writes:

I wish that I had the talent to write such sentences. Unfortunately, these statements are the opposite of what cost-benefit analysis actually tries to do.

Let me first illustrate with a recent proposal by Janet Yellen and supported by 3,500 economists (economics being the intellectual source of cost-benefit analysis). This proposal argued for a carbon tax, which would shift energy production to more costly methods of producing energy and reduce present consumption for the benefit of future generations. At the same time, the proposal suggested that the proceeds of the tax go to those with low income. Simply put, the cost-benefit analysis argued that the benefit to future generations outweighed the cost to the present generation. Note that […] future well-being is taken into account and there is no discussion of profit.

Robinson’s pitiful reply was:

In our present limbo, when so little can be known about future demand for energy, Janet Yellen’s proposal for a carbon tax showering benefits on the poor and on posterity looks a little dreamy. It is telling that no actual policy is cited to show that these admirable impulses have yielded anything more substantive than 3,500 signatures.

The puzzling absence of understanding of and interest in CBA in Robinson’s essay does makes perfect sense if we understand her to use the term “cost-benefit analysis” as a stand-in for “capitalism”. But Robinson is a professional writer and surely no professional writer would be so careless (or underhanded) in their choice of words. Or, put more charitably, maybe she is not talking about CBA as a way of deciding between possible courses of actions, but as a practice – as an activity that humans engage in in order to achieve some goal (in her view, making money). On this view, her critique of CBA is more like anti-gun activists’ critique of guns – sure, they are not intrinsically bad, but they enable, or encourage even, evil practices.

I don’t think CBA encourages evil practices. I think we live in a world that has finite resources. I think we are in triage every second of every day. I think we have to decide how to do the most good with the money, time and attention available to us. I think CBA is a fine way of making such decisions, because I agree with Robinson that the purpose of CBA is “to realize a maximum of benefit at a minimum of cost”. Robinson does not say how she thinks we ought to make such decisions, because her fantasy is that we don’t have to choose – that, as Holly Elmore puts it, “agreeing to choose is already going too far”. But the alternative to making rigorous decisions is not making no decisions at all, but making bad decisions.

A quick primer. CBA is a decision procedure that sums rewards and subtracts costs associated with each of a set of actions, allowing us to choose the action with most benefit for the cost. It is similar to a cost-effectiveness analysis, only instead of measuring everything in utility, it measures everything in money. But it can be used to make decisions about any desired outcome, not only profit. You just translate the intangible outcome into a monetary value.[1]

Robinson writes that bad and shortsighted decisions are made via “a cost-benefit analysis engaged in subrationally”. This makes no sense. If she means by rational thinking the kind of thinking that helps us make good decisions, then she is saying that CBAs done in the kind of thinking that doesn’t help us make good decisions, leads to bad decisions. That is a tautology. If she means by rational thinking truth-seeking, then she has tripped on her first step, because CBA is not a tool for truth-seeking, but for decision-making. If she means that CBAs are done subconsciously (“prior to thinking”) then that is obviously false. Carrying out a CBA involves actively evaluating possible actions based on their expected outcomes, and putting numbers on things; subconscious decision-making is antithetical to CBA.

Now, cost-effectiveness analyses can be misleading in a number of ways, and it is important to keep those limitations in mind. They are not everything or for every situation. But they can be very useful in practical decision-making, in everything from hospital staff deciding how to spend a budget so as to help as many patients as much as possible to individuals making decisions about where to live or which career to choose.

On Extreme Poverty #

What does it matter, whether someone thinks CBA is useful or evil? It matters because jettisoning tools for rigorous analysis means one is that much more likely to make flawed analyses, of which Robinson herself is proof. For example, she writes:

Employing [Chinese workers] in preference to American workers would sidestep the old expectation that a working man or woman would be able to rent a house or buy a car. The message being communicated to our workers is that we need poverty in order to compete with countries for whom poverty is a major competitive asset. The global economic order has meant that the poor will remain poor. There will be enough flashy architecture and middle-class affluence to appear to justify the word “developing” in other parts of the world […]

Let me quote Donald Wittman again:

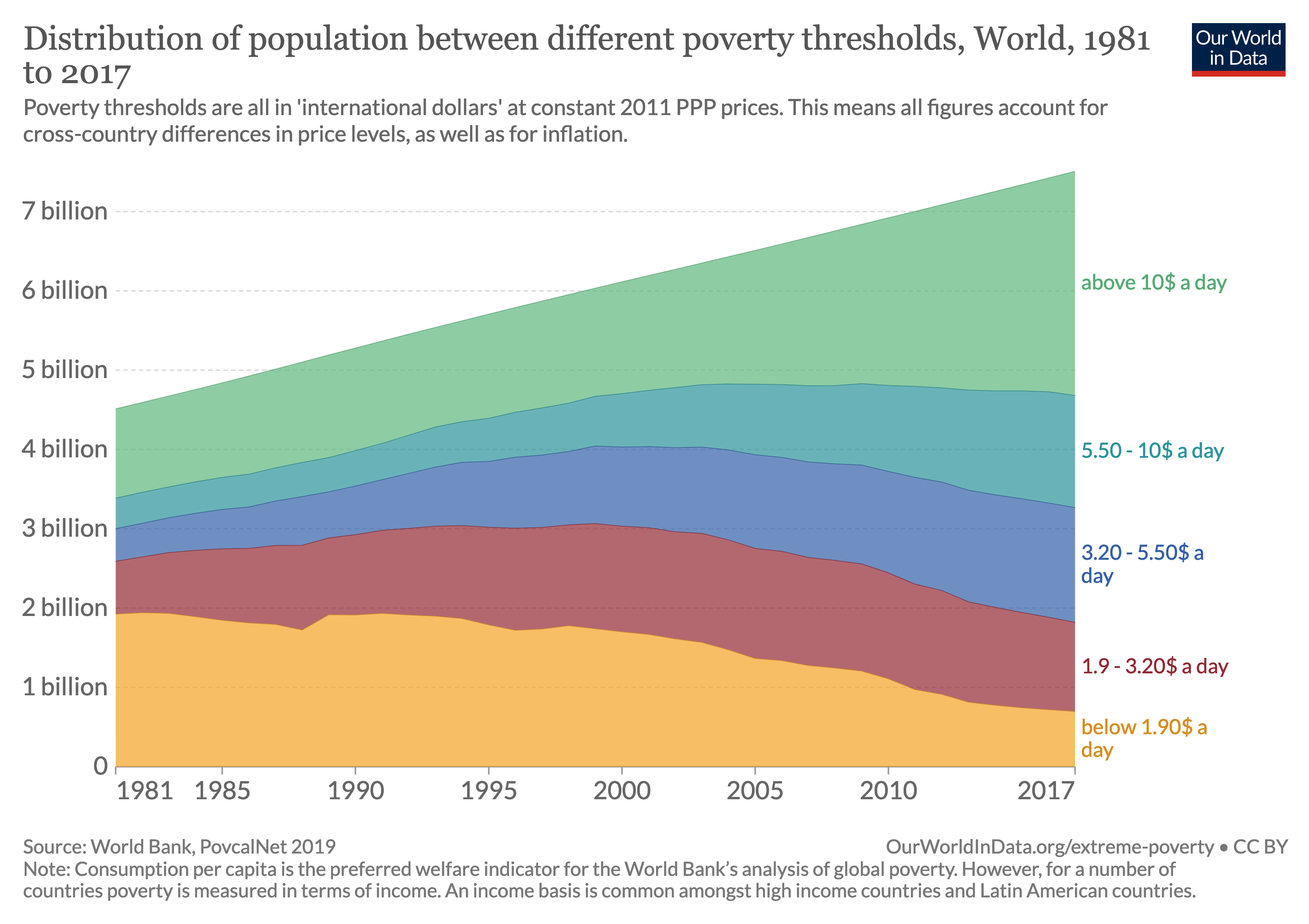

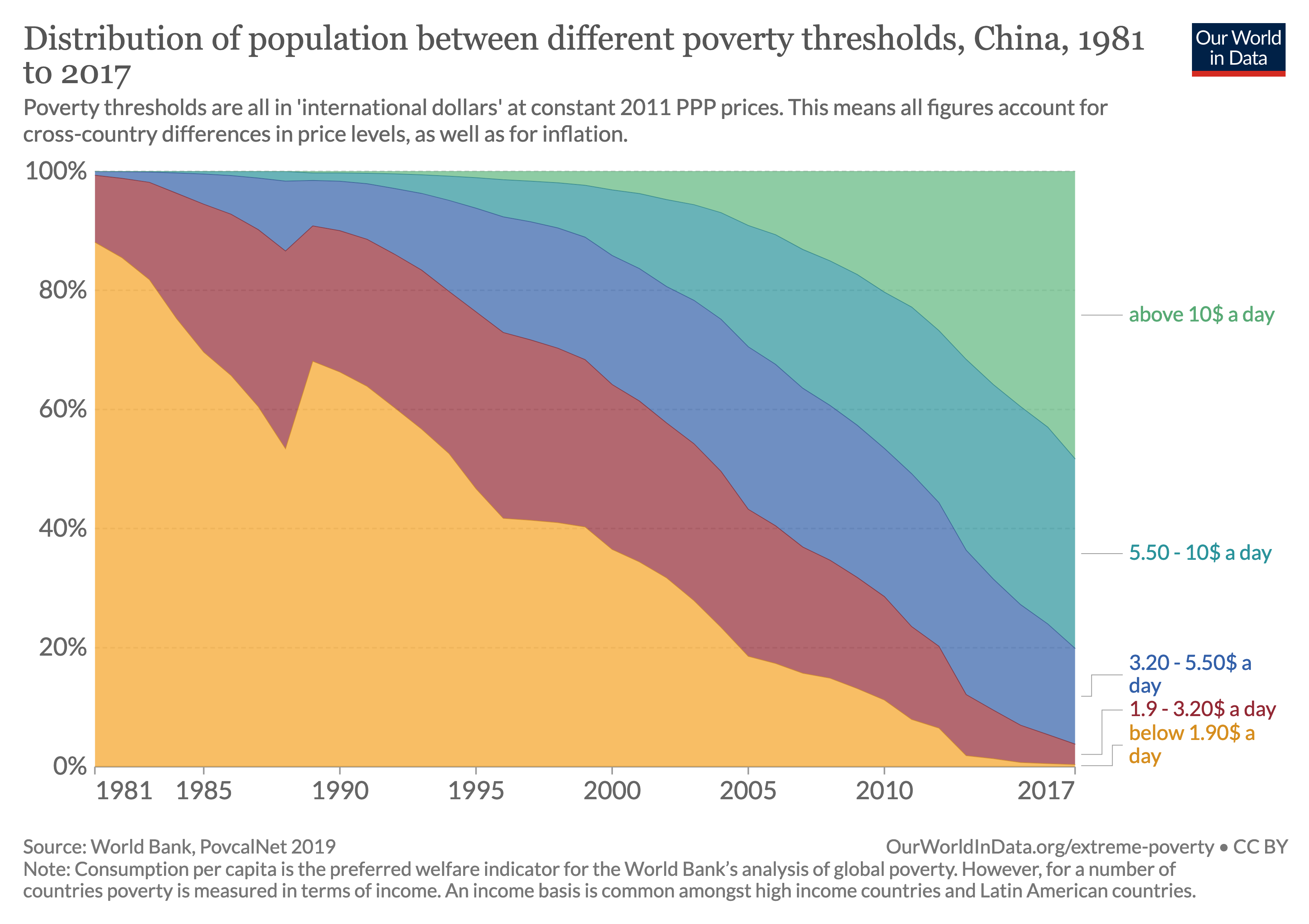

On the contrary, the global economic order (freer trade between countries and less government control of the economy) has meant that hundreds of millions of the poorest of the poor, those in China and India, have escaped (extreme) poverty, and tens of millions if not more have moved into the middle class in the last few decades.

And Robinson’s pitiful reply:

[Wittman] speaks of millions rescued from “(extreme) poverty” – to enjoy the comforts of unmodified poverty, presumably. Those parentheses are his. Let us assume that the improvements he describes are real and meaningful, weighed against environmental and other costs. Whether these changes would be sustainable as the American economy, so long the engine of the world economy, is dismantled is another question. So many variables have been added to the situation that the old answers, whether yes or no, are now strictly hypothetical. We do know and can say with confidence that issues of social justice in this country, economic in their origins and their effects, have grown worse.

I am shocked to read a passage so full of contempt for people in poverty. I think maybe Robinson does not see just how poor the global median household is. In 2013, its income was something like $168 per month (Hellebrandt and Mauro 2015). And half of all households in the world are even poorer than that! (I recommend having a look at Dollar Street to get a glimpse of what this looks like.)

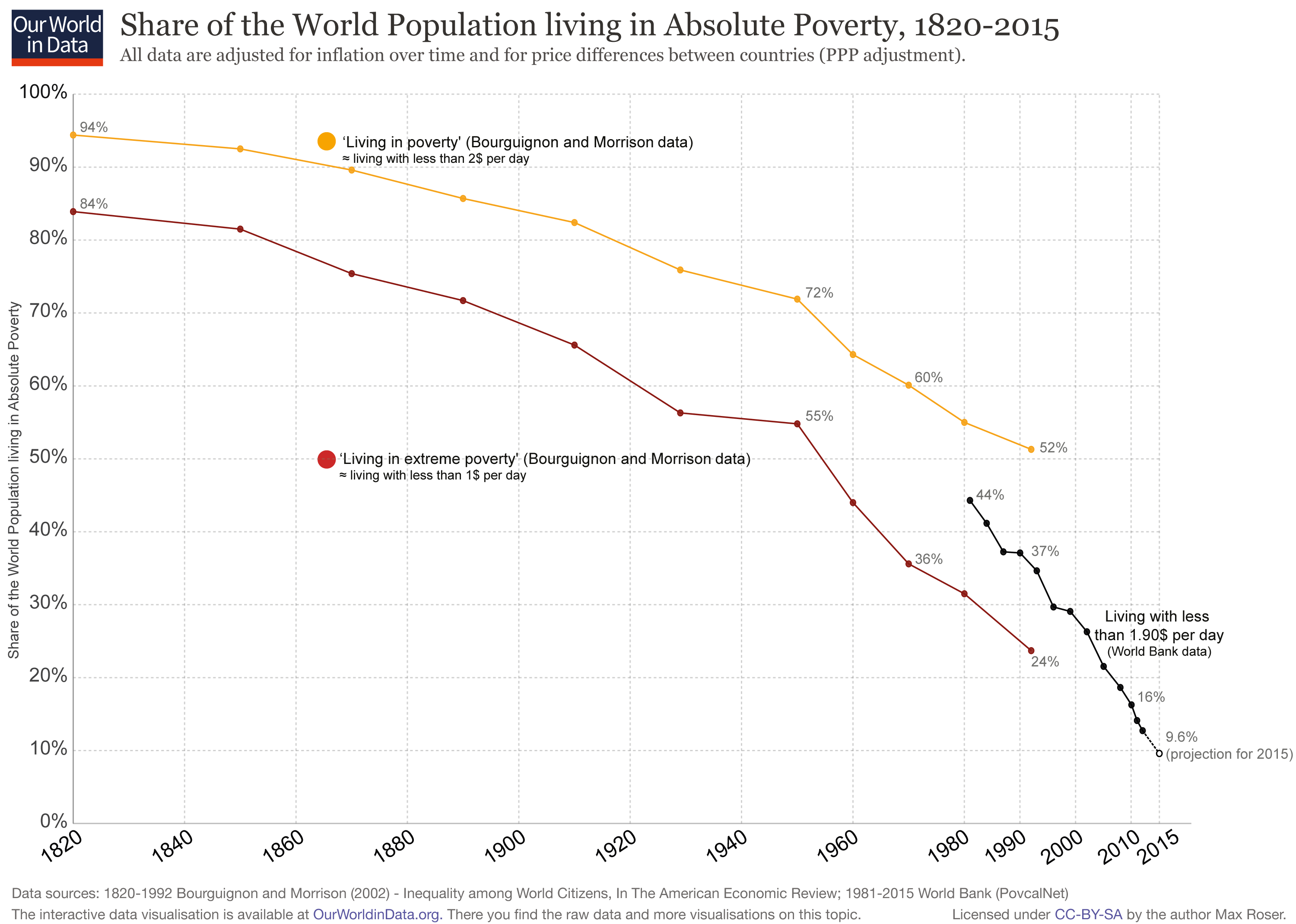

The World Bank defines extreme poverty as living with an income of less than $58 per month (around two dollars per day). Before the Industrial Revolution, 19 out of 20 people lived on less than that amount (adjusted for inflation and purchasing power); now one in ten do (Ord 2020). And as Toby Ord writes, “People in richer countries are sometimes disbelieving of these statistics, on the grounds that they can’t see how someone could live at all in their town with just $2 each day. But sadly the statistics are true, and even adjust for the fact that money can go further in poorer countries. The answer is that people below the line have to live with accommodation and food of such a poor standard, that equivalents are not even offered by the market in richer countries.” So the fact that this sort of thing has happened

is not something to be dismissed as “enjoy[ing] the comforts of unmodified poverty”, is not an improvement to be grudgingly admitted, but, on the contrary, is something truly great, a thing that should fill our hearts with joy and gratitude and inspiration.

In a conversation with Barack Obama that took place seven years ago, Robinson said:

Look at, frankly, China. China has a vile ecology around its industrial centers. It’s running out of appropriate cheap labor. And it’s going into crisis. And what does that mean? It means that all of that capital will bundle itself up and land in another place that’s relatively more advantageous. So what are we competing with? We run China into the ground, is that our great mission?

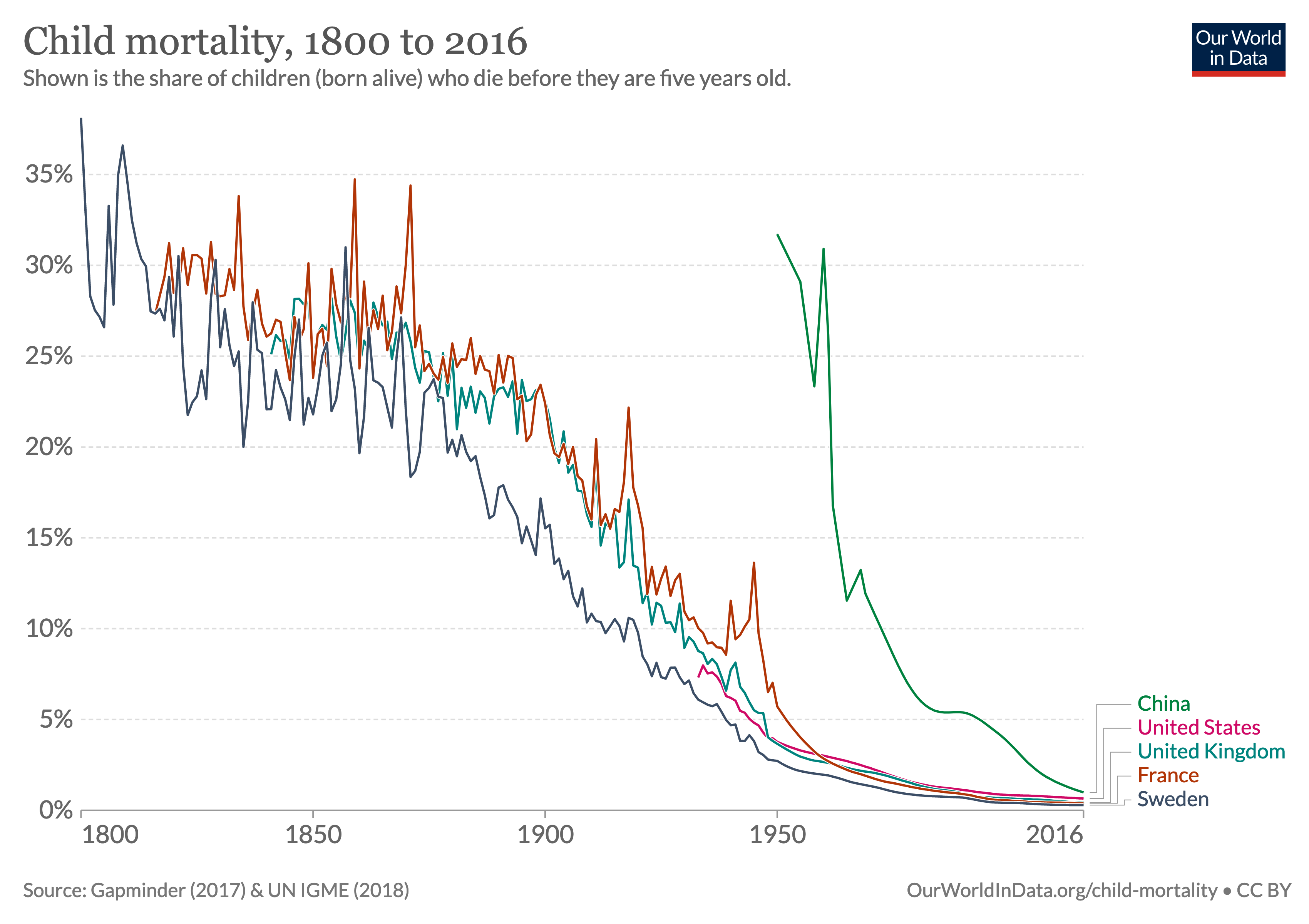

Here is what running China into the ground (as if the Chinese have no autonomy at all) looks like:

Now, I don’t know what variables Robinson refers to, nor which old answers are now merely hypothetical, nor what all that is meant to signify, but I do know that these changes are real and important and need to be taken seriously. Robinson does not take them seriously, because numbers are mere ornaments to her.

Conclusion #

I am not a Panglossian. I know that things are really bad for a lot of people out there. That is why it is necessary to look at the world rationally, in order to see what works and what doesn’t, how we can help people achieve their goals and what prevents them from doing so. If Marilynne Robinson were truly interested in questioning her own thinking, Wittman’s remarks about global poverty should not have provoked in her a sneering dismissal, but genuine curiosity. If she really wanted to “create a new vocabulary or terrain” for herself, then she might have seen some of the virtues of cost-benefit analysis and adopted it as a tool in her toolbox. Because I take it that she is so interested and that she does so want, I can only conclude that either she keeps making flawed inferences, or she has other goals in conflict with those.

Appendix: How Bad Are Things in America? #

I said I was not really interested in Robinson’s argument that the state of things in America is bad. But I did make some epistemic spot checks in order to get an idea of Robinson’s epistemic rigour.

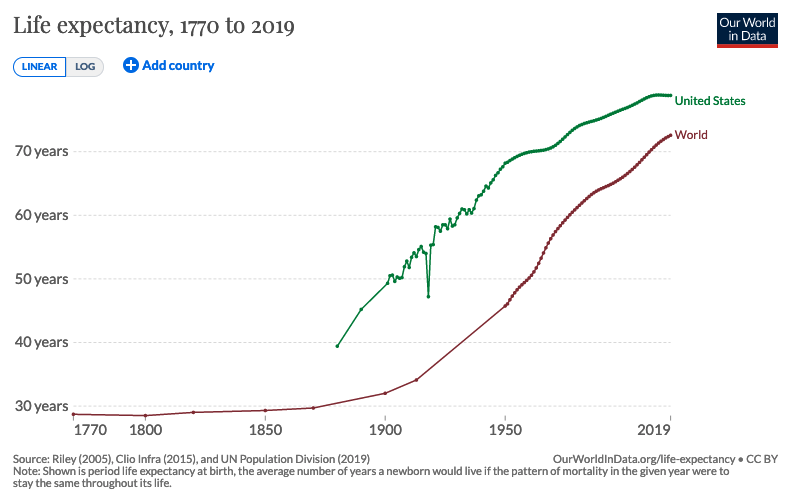

One, Robinson mentions “reports of declines of life expectancy in America”. Is American life expectancy down? I would say it looks more like the increase has plateaued (whereas it is steadily rising in the world in general) (Max Roser and Ritchie 2013):

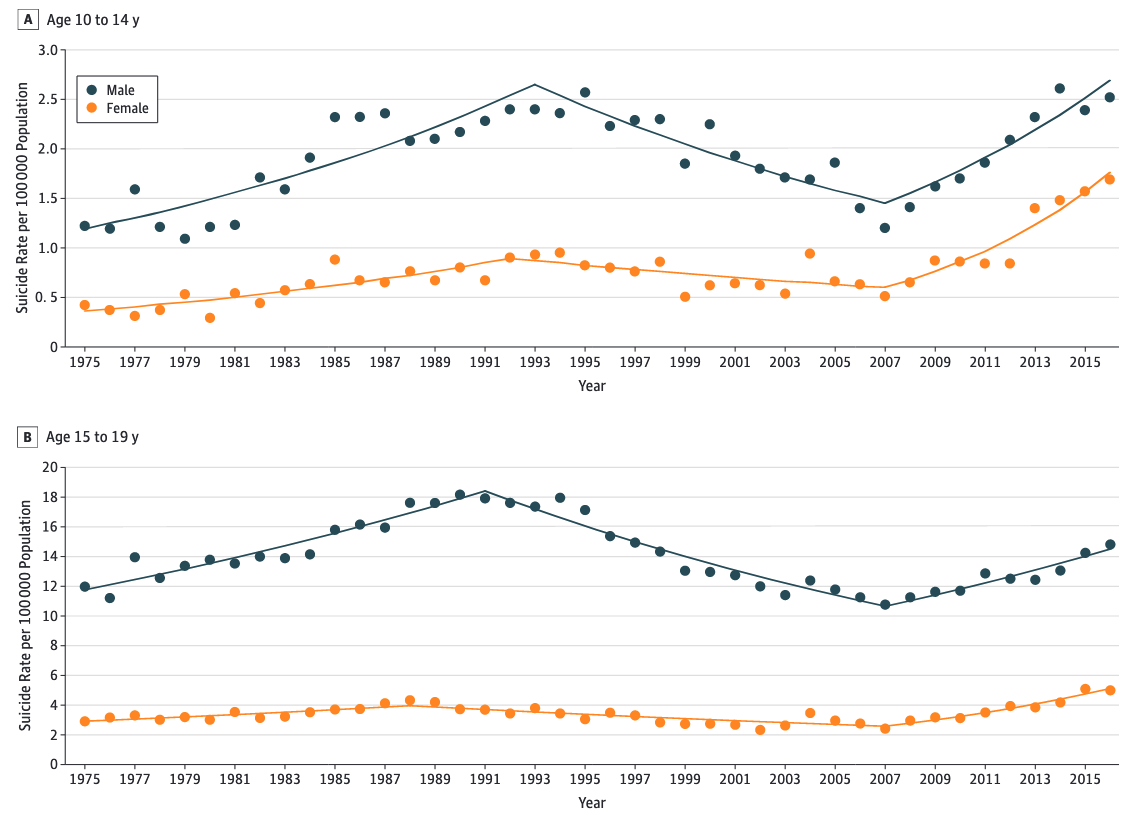

Two, Robinson mentions “rising rates of suicide”. Suicide has been increasing in America recently, but is now at rates comparable to those in the early 1990s (Ruch et al. 2019). Here is a graph showing suicide rates among youths (but I believe the trend is similar for the general population):

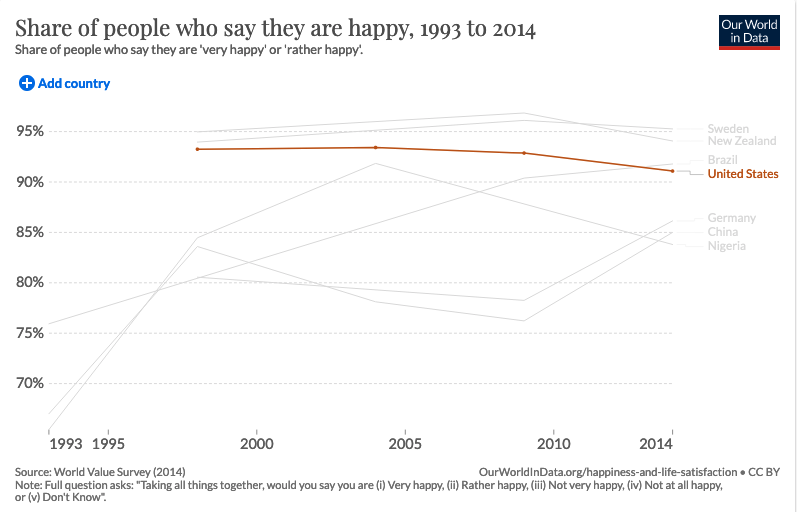

Three, Robinson mentions a “decline in hope and purpose”. I wasn’t able to find data about optimism over time in America, but there is a slight decline in self-reported happiness in America (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2013):

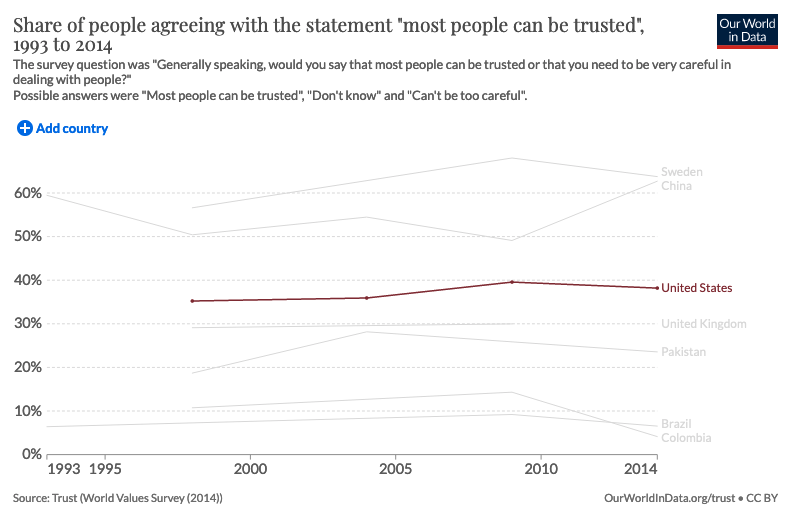

But trust seems stable (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2016):

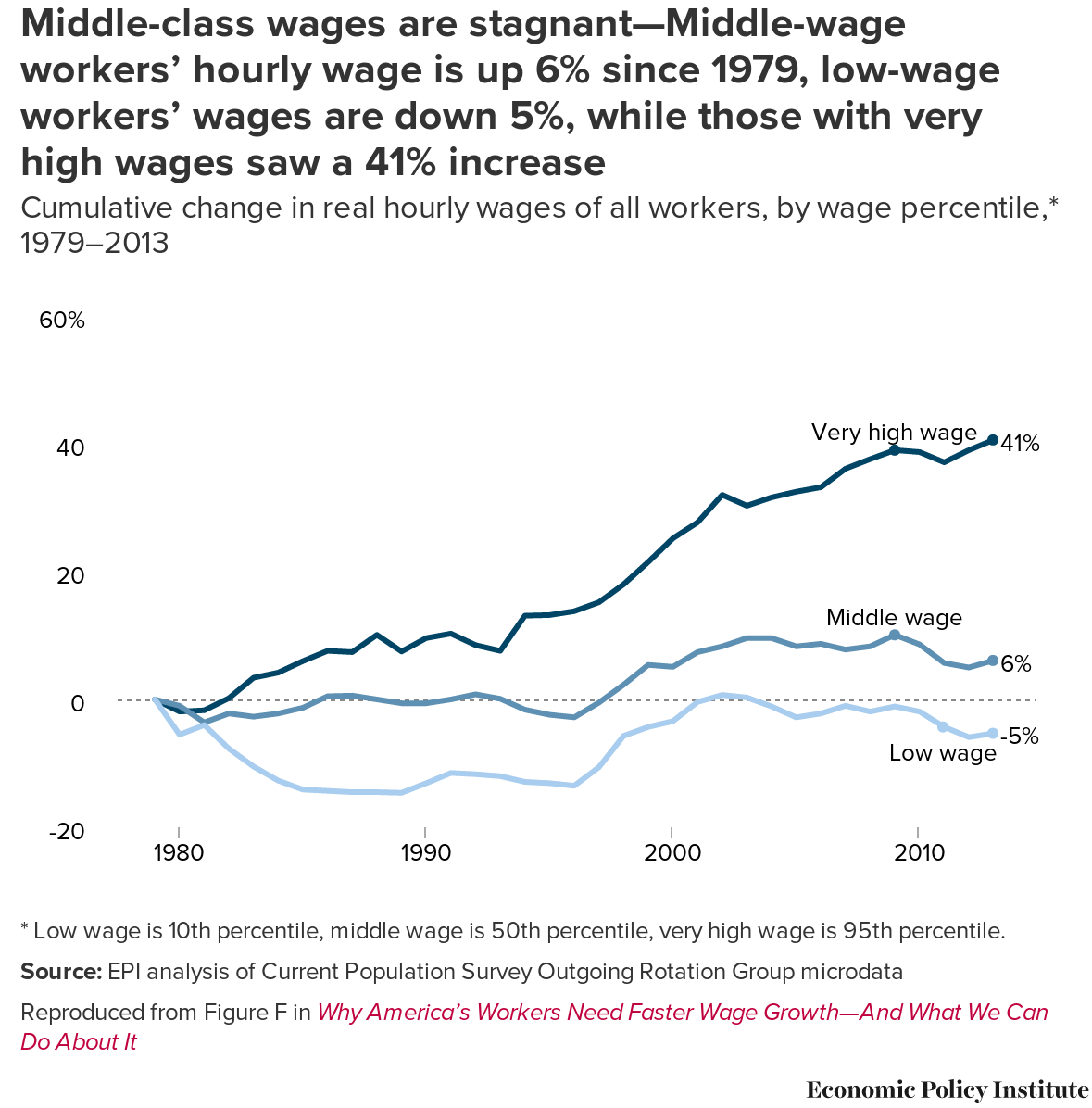

Finally, what about Americans’ economic situation? Robinson writes that “workers’ real wages have fallen for decades in America”. It looks more correct to me to say that they have stagnated:

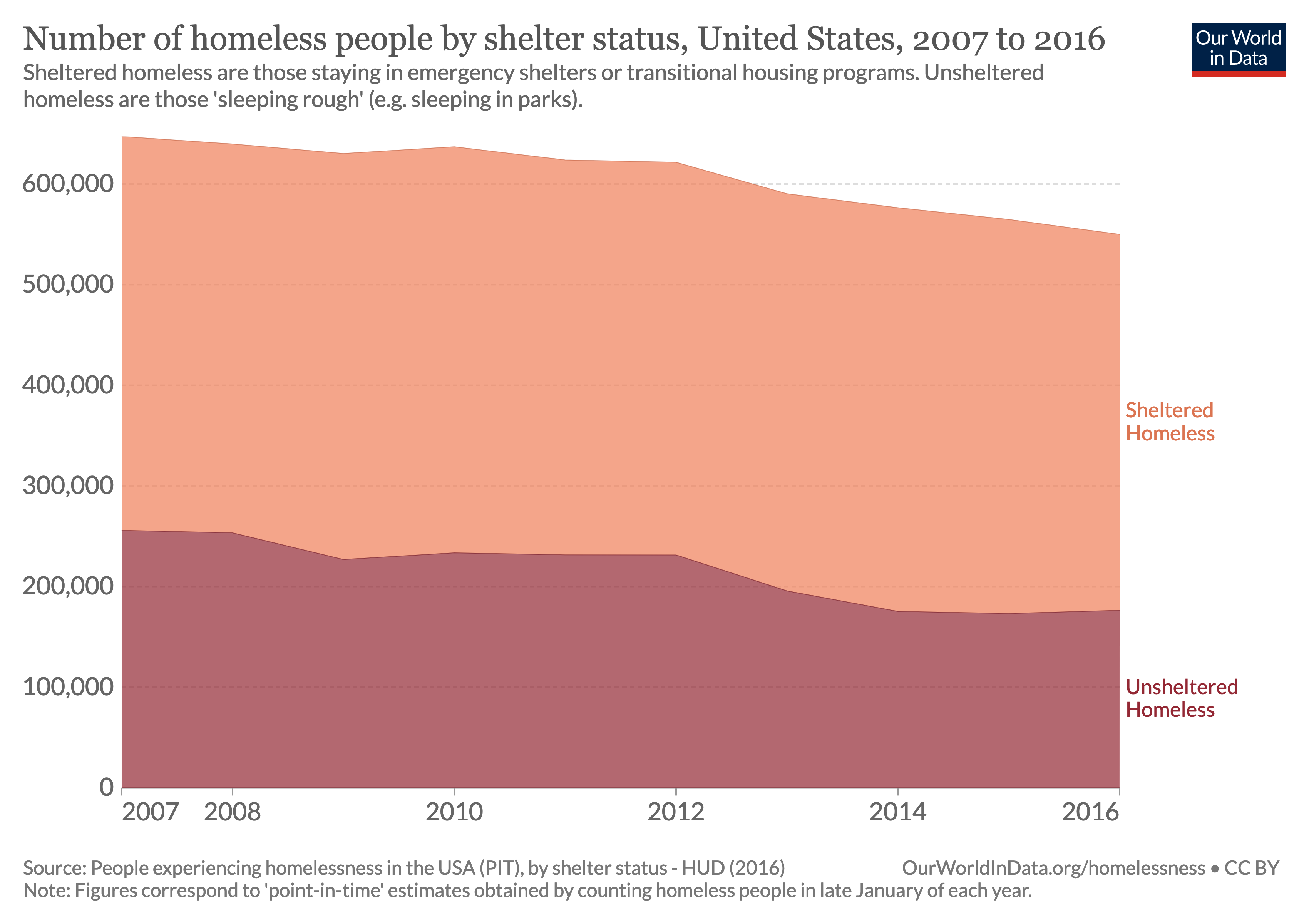

The shockingly large number of homeless people is decreasing (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2017):

In sum, I think things have plateaued or declined in America recently, though it doesn’t quite look catastrophic, let alone like a “crisis of civilization” (and the trend does not hold for the world as a whole). Robinson comes off okay here, but not great.

References #

Footnotes #

Various issues come up when putting a monetary value on intangibles, or for that matter when measuring pure utility – various biases can skew our judgment, for example (Baron 2000). ↩︎