Utilitarianism Expressed in Julia

I had been looking for a small programming project for learning the basics of Julia when I had the idea of modelling a moral system in code. Due to its computational nature, Utilitarianism seemed a likely candidate. Any moral system involves functions in the sense that, given a state of the world and one or more possible actions, it can tell you whether those actions are right or wrong, or which action is better than the others. But Utilitarianism goes beyond that, because it does this by putting numbers on things, aggregating those numbers and mathematically comparing the results. That is probably one reason why it is so popular among programmers.

Quoting utilitarianism.net quoting Peter Singer, Utilitarianism says that, “as far as it is within our power, we should bring about a world in which every individual has the highest possible level of wellbeing”. There are of course different ways of interpreting and implementing that in practice, and as a result there are many different variants of Utilitarianism. This will become obvious as we are faced with design choices in our implementation.[1]

For example, what is well-being, or utility? Let us assume that it is the average of all the positive and negative experiences in the life of an individual. I will call such an individual a receptacle because what is relevant about it here is the fact that it can contain, so to put it, utility. But it could be a human, or an animal, or an alien even.

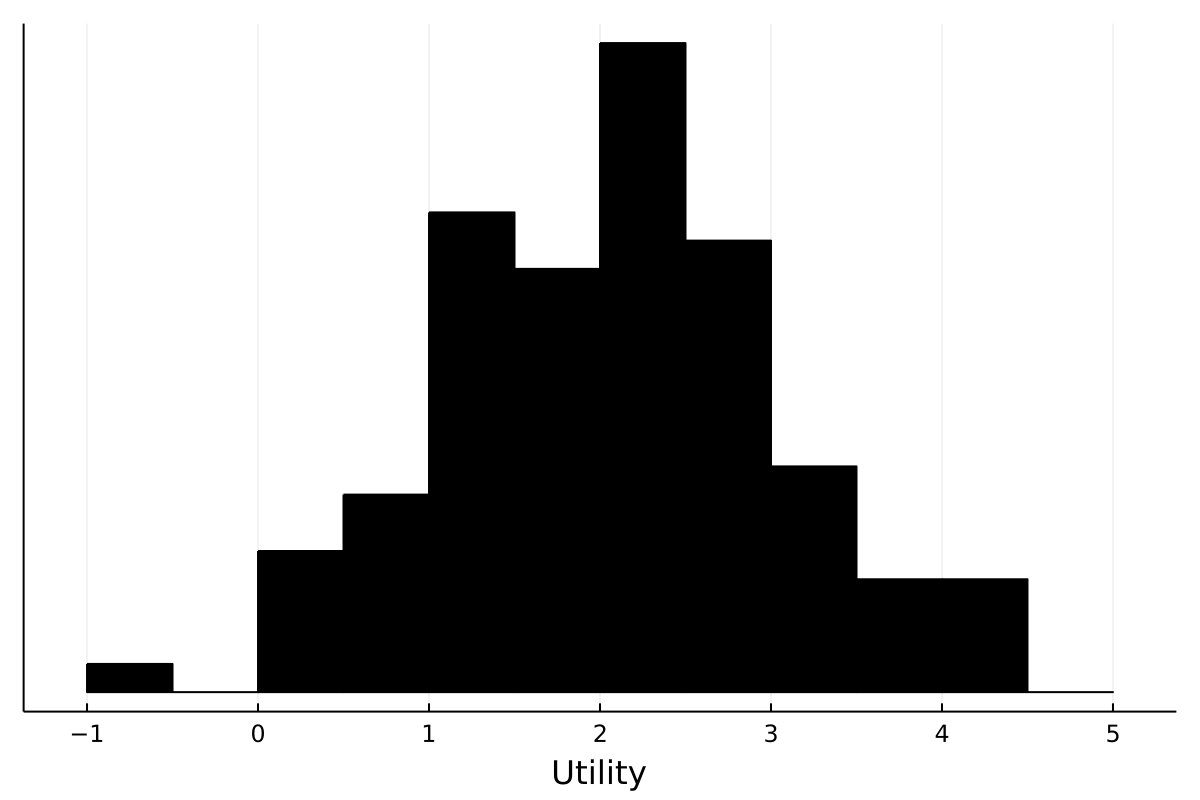

Let us also assume – why not? – that utility is normally distributed around a value of two, two being our baseline value. Receptacles above two have mostly happy lives, receptacles below two have mostly unhappy lives, and receptacles below zero have lives that are objectively not worth living at all.

So a receptacle is just a floating-point value, and a world is just an array of receptacles:

const Receptacle = Float64

const World = Array{Receptacle}We can create two functions for generating these:

using Random

genreceptacle() = randn() + 2 # standard deviation 1

genworld(n::Int = 100) = map(_ -> genreceptacle(), zeros(n))Calling genworld() gives us our baseline world. We can plot it[2]

using Plots, StatsPlots

histogram(genworld())to get a nice visual representation:

So there are a bunch of receptacles living normal lives around the baseline value, some lucky few with utilities of three or four and some poor devils with utilities below one or even in the negative.

Classical Utilitarianism #

Now we have to measure how much utility there is in total in a world. Otherwise we cannot compare worlds, and we need to compare worlds in order to compare actions, because each action produces a different world. In Classical Utilitarianism, the one of Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick, we take the sum of the utilities of all the receptacles:

getutility(world::World) = sum(world)(Remember, this code works because a world is just a vector of floating-point values.)

In any given situation, at any moment, with countless possible actions available to us, the purpose of a moral system is to tell us which one to choose. An action is just a function that maps a world to another world. We can model the decision process with a function, act, that takes as its arguments a world and a list of possible actions, and returns the index and resulting aggregate utility of the best action. It does this by first calling each action function with the given initial world and then sorting the resulting world vector by the amount of aggregate utility in it. (It also prints the ranking and aggregate utility of all possible actions, to help us understand what is going on. This is not really great code but it will serve our purposes, so actually, on second thought, maybe it is great code.)

function act(world::World, possibleactions::Array{Function})

result = sort(

map(((i, action),) -> (i, getutility(action(world))),

enumerate(possibleactions)),

by = ((i, world),) -> world,

rev = true

)

println("Got actions and consequences: $result")

first(result)

endThe simplest of actions, doing nothing, is just the identity function:

donothing(world::World) = worldLet us test all this. Say you are faced with two options, doing nothing or telling your a friend about a great blog, thereby increasing their lifetime utility by a small amount. We can implement that second action by slightly adding to the utility of the first element of the input world vector. Which action should you choose?

julia> act(genworld(), [donothing, w -> [(w[1] + 0.1);w[2:end]]])

Got actions and consequences: [(2, 204.72313361883513), (1, 204.62313361883514)]

(2, 204.72313361883513)Telling your friend about the blog produces a world with more utility than doing nothing at all, so that is what you should do according to Classical Utilitarianism. But that is too easy. It is a well-known fact that philosophers and especially utilitarians love pushing people in front of trolleys. Let’s say you have the option of pushing one receptacle in front of a trolley in order to save five who would otherwise die. We have two actions:

killonetosavemany(world::World) = world[1:end-1]

letmanydie(world::World) = [world[1];world[end]]Here we make another few assumptions. We assume that the survivors, including yourself, are not affected by the event. We assume that the event does not affect anyone outside the seven participants. And we assume more generally that whatever action you choose does not influence the world beyond directly leading to one or five deaths. Classical Utilitarianism clearly recommends killing the one to save the five:

julia> act(genworld(7), [killonetosavemany, letmanydie])

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 10.51786771130836), (2, 4.195472029023403)]

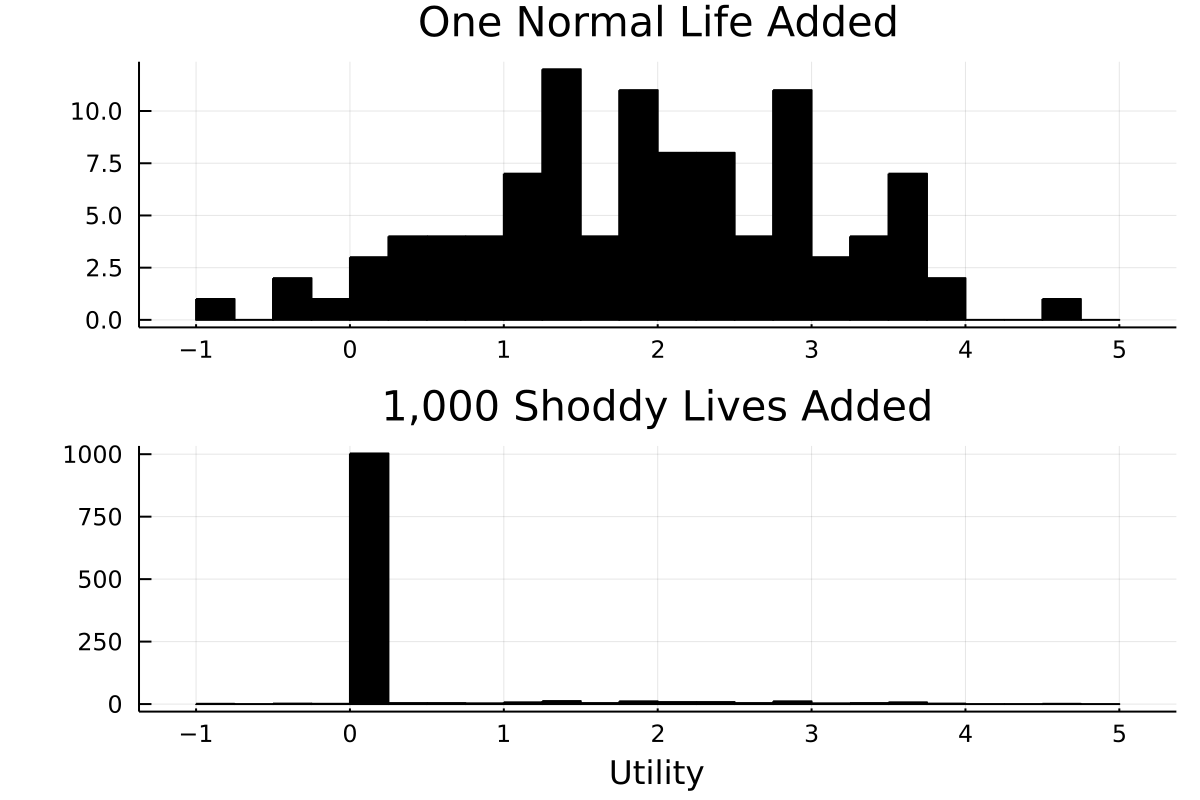

(1, 10.51786771130836)Now let’s try something more difficult. What if we had the option of either adding one normal life to the world, or adding one thousand lives that are full of suffering and only barely worth living?

addnormallife = w -> [w;genreceptacle()]

addshoddylives = w -> [w;repeat([0.01], 1000)]Classical Utilitarianism recommends adding the one thousand lives barely worth living:

julia> act(genworld(), [addnormallife, addshoddylives])

Got actions and consequences: [(2, 227.14957726154114), (1, 219.17418869670146)]

(2, 227.14957726154114)But this seems pretty counterintuitive. In fact, it seems so counterintuitive that it has its own name in philosophy: this is the Repugnant Conclusion famously described by Derek Parfit.[3] If we plot this difference

histogram(

[addnormallife(genworld()), addshoddylives(genworld())], layout = (2, 1),

title = ["One Normal Life Added" "1,000 Shoddy Lives Added"])it is really clear how the chosen world is a far more miserable one on average than the alternative:

(At this point you may be thinking that something here is a little bit weird. What is so special about two, our baseline value? If we had all lived in a world where this action happened, we would have set our baseline to 0.1 and called that “normal”. None of us would have taken it to be terrible that so many of us lived such bad lives, because they would all have been average lives. Of course we all prefer the world with the average utility of two, because to us those lives with a utility of 0.1 seem so bad as to be basically not worth living. But in fact they are by definition worth living. In other words, perhaps we should not trust our intuitions here. This is one point that Michael Huemer makes in arguing that utilitarians should accept the Repugnant Conclusion.[4])

Average Utilitarianism #

One way to escape the Repugnant Conclusion is by taking, instead of the sum of the utilities in the world, the average. In other words, we rewrite our utility function[5]:

using Statistics

getutility_avg(world::World) = mean(world)Now we will also need to modify our act function to accept an arbitrary utility function:

function act(

world::World, possibleactions::Array{Function}, utilityfunc::Function)

result = sort(

map(((i, action),) -> (i, utilityfunc(action(world))),

enumerate(possibleactions)),

by = ((i, world),) -> world,

rev = true

)

println("Got actions and consequences: $result")

first(result)

endNow we have everything we need for Average Utilitarianism. Armed with this new perspective, we can evade the Repugnant Conclusion, because adding many lives barely worth living reduces the average world utility:

julia> act(genworld(), [addnormallife, addshoddylives], getutility_avg)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 1.9904407716146917), (2, 0.18986181251211073)]

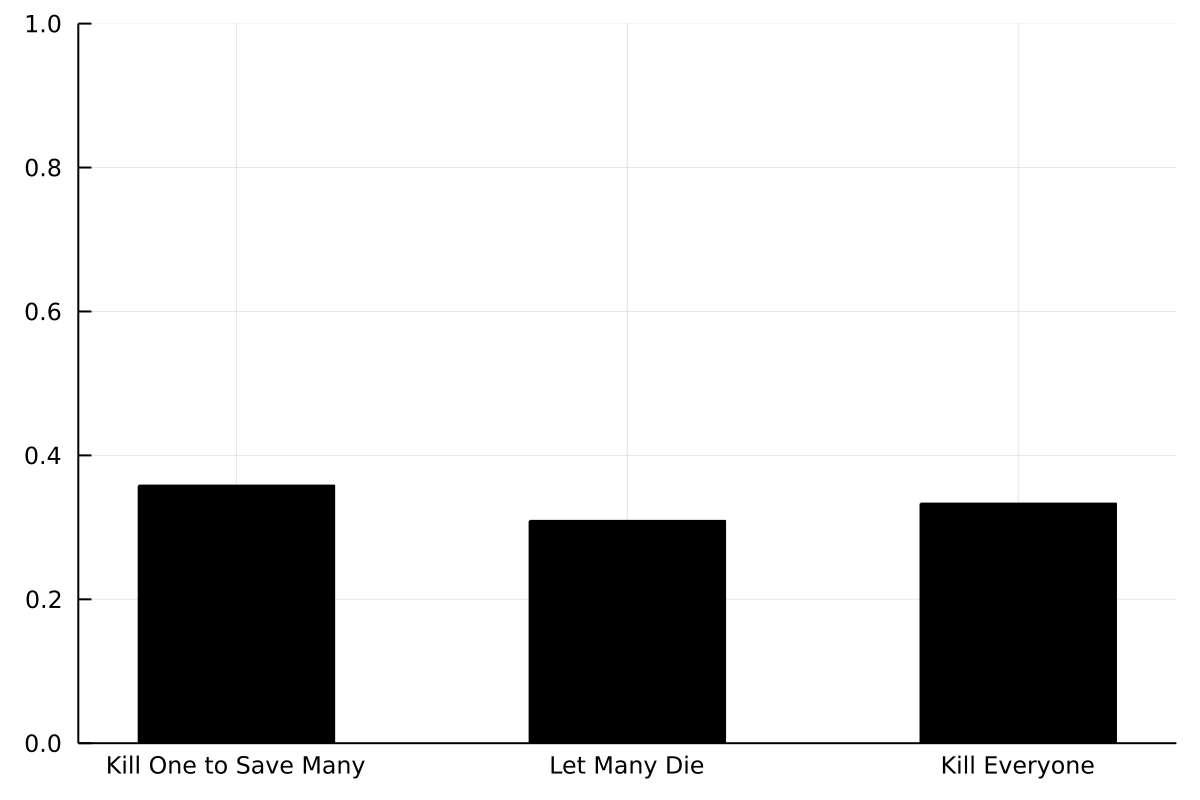

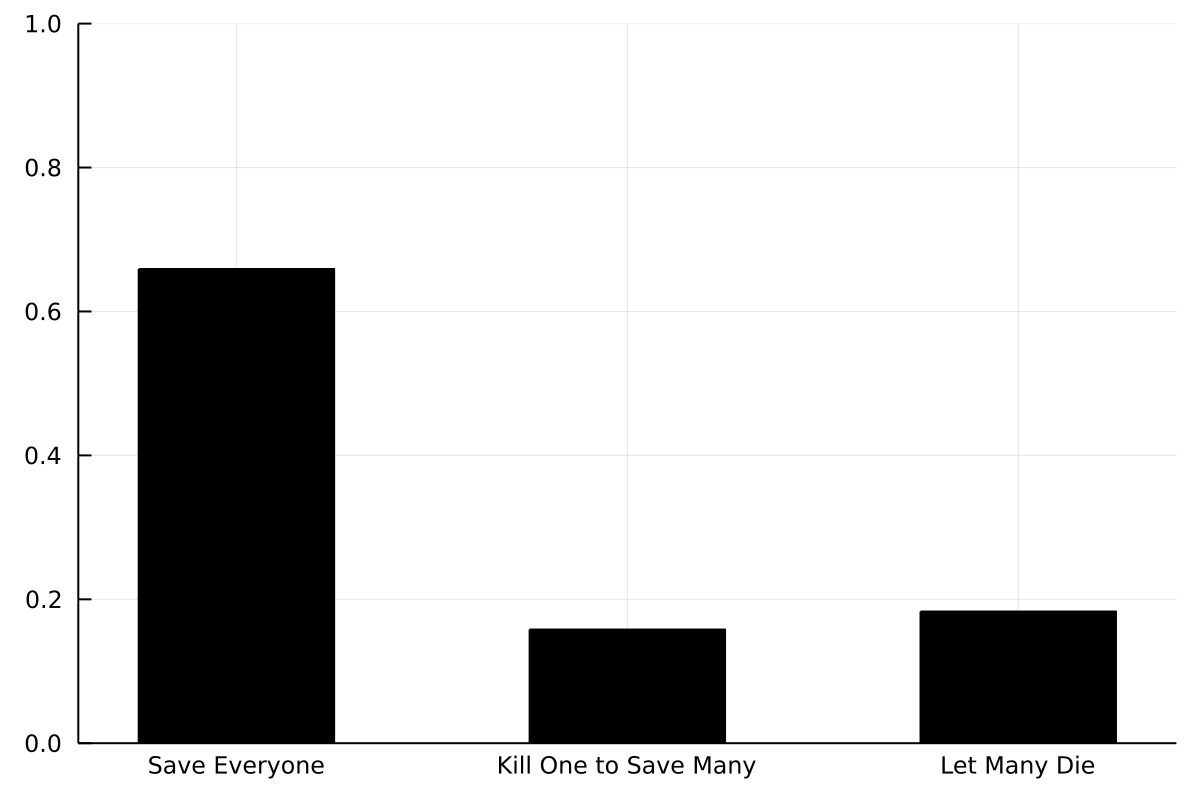

(1, 1.9904407716146917)Unlike the classical version, Average Utilitarianism is not sensitive to how many receptacles there are in the world. Therefore, because we assumed the same utility of all the participants (with some random variation), the Trolley Problem is pretty much a toss-up. We can confirm this by running the experiment one thousand times and counting how often each action was chosen. Let us while we are at it also add an additional, sadistic option, which is to kill everyone except yourself:

killeveryone(world::World) = [world[1]]

function runtrolley_avg()

((choice),) = act(

genworld(7), [killonetosavemany, letmanydie, killeveryone],

getutility_avg)

choice

endWe can then run the simulations and count the choices

n = 1000

trolleyresults = map(_ -> runtrolley_avg(), zeros(n))

counted = map(i -> count(j -> j == i, trolleyresults), 1:3) ./ nand finally plot the result:

bar(counted)

The sadistic option here is, according to Average Utilitarianism, just as good as the others. In fact, Average Utilitarianism recommends killing receptacles whose lives are only a fraction below average:

julia> world = genworld()

julia> act(

[world;mean(world)-0.1], [donothing, w -> w[1:end-1]], getutility_avg)

Got actions and consequences: [(2, 2.015363273532925), (1, 2.014373174523024)]

(2, 2.015363273532925)(Again, we are assuming that the action is isolated. The victim has no friends or family members who will grieve over their death or who have depended on them for support.)

Because of these and other problems, Average Utilitarianism is, so I gather, not very popular among philosophers.

Critical-Level Utilitarianism #

In Classical Utilitarianism, we said that adding new lives were good if those lives were worth living, in other words if they had a utility above zero. In Critical-Level Utilitarianism, we change the threshold (the critical level) from zero to another number.[6] For example, we could say that adding a new life is good iff it has a utility at or above one. In effect, this means that we are adding a penalty proportional to the number of receptacles there are. Critical-Level Utilitarianism ought to fix our problems with the original Repugnant Conclusion while also not recommending killing receptacles whose lives are only a fraction below average, as does Average Utilitarianism. The implementation is easy:

getutility_cl(world::World) = sum(world .- 1)Of course we could have picked any number to subtract. This is only one Critical-Level Utilitarianism – there are endless more. This one easily escapes the Repugnant Conclusion:

julia> act(genworld(), [addnormallife, addshoddylives], getutility_cl)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 104.01597699786336), (2, -887.2670752401644)]

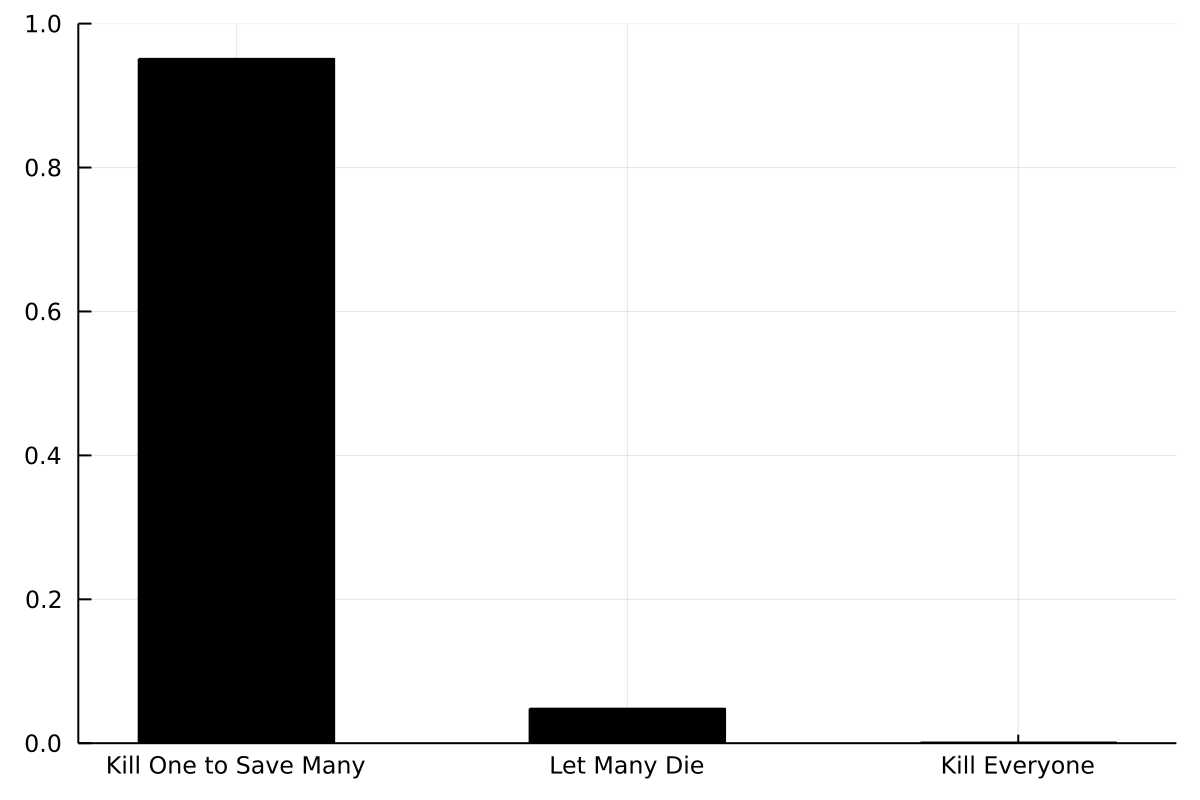

(1, 104.01597699786336)What about the Trolley Problem? We can make our function more generic and run another one thousand simulations with the new utility function:

function runtrolley(

utilityfunc::Function, possibleactions::Vector{Function}, n::Int = 1000)

function runexperiment()

((choice),) = act(genworld(7), possibleactions, utilityfunc)

choice

end

choices = map(_ -> runexperiment(), zeros(n))

counted = map(i -> count(j -> j == i, choices), 1:3) ./ n

counted

end

result = runtrolley(

getutility_cl, [killonetosavemany, letmanydie, killeveryone])

bar(result)

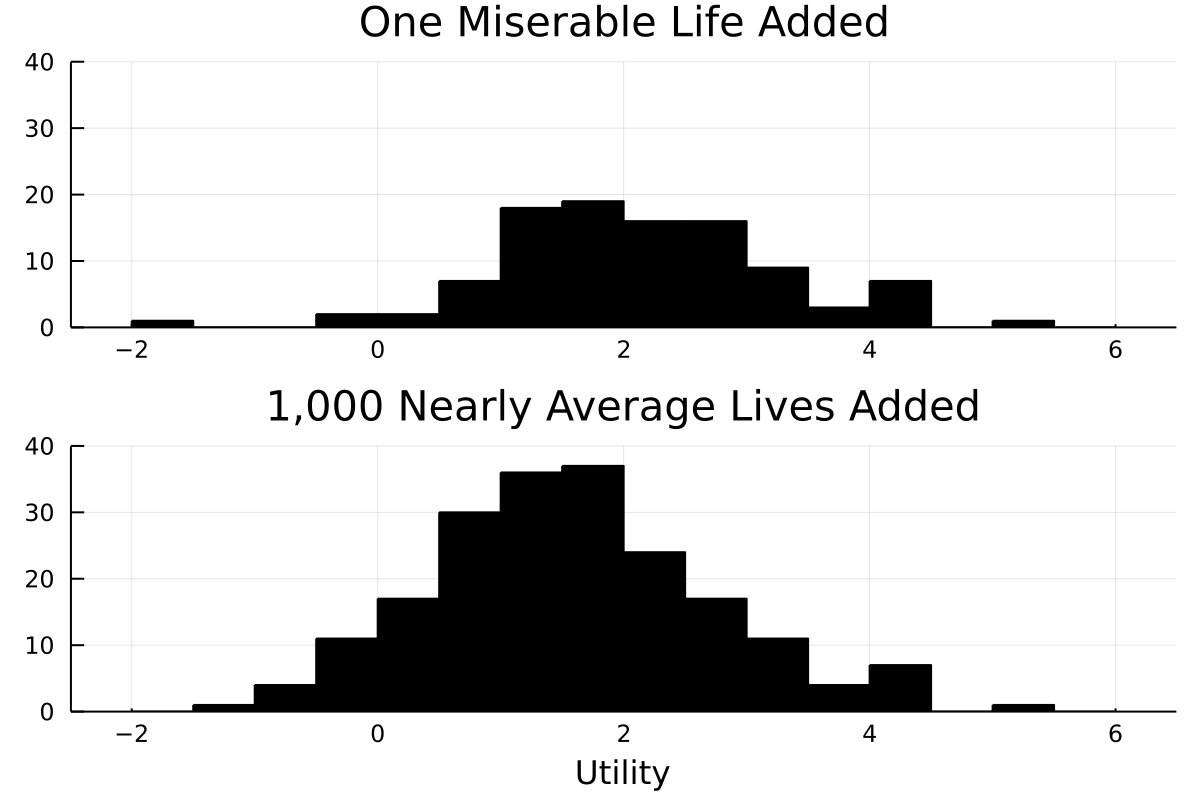

Once again it depends on the configuration of the particular receptacles we start the experiment with, but on average Critical-Level Utilitarianism prefers killing the one to save the many, and likes the sadistic action the least. But had we set a higher critical level, say at two, it would sometimes recommend killing everyone. That is because, with a critical level at two, we consider any receptacle with a utility below two to have a life not worth living, even if they themselves do not do so. That leads to some pretty weird conclusions, for instance that it is better to add one truly miserable life, full of torture and agony, than it is to add one hundred lives only barely below the critical threshold.[7]

addmiserablelife = w -> [w;-2]

addmanybelowaveragelives = w -> [w;map(_ -> genreceptacle() - 0.1, zeros(1000))]Running the simulation we see that Critical-Level Utilitarianism (at our chosen level) recommends adding the truly miserable life:

julia> act(

genworld(), [addmiserablelife, addmanybelowaveragelives], getutility_cl)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 108.01495726536602), (2, 91.56568171210701)]

(1, 108.01495726536602)We can also plot the distributions:

world = genworld()

histogram(

[addmiserablelife(world), addmanybelowaveragelives(world)], layout = (2, 1),

title = ["One Miserable Life Added" "1,000 Nearly Average Lives Added"])

Here is another possible weirdness with all the previous versions of Utilitarianism. Say we are faced with the choice of making the worst-off receptacle in the world happier and making the best-off receptacle in the world happier. So we can either remove the agonising suffering of some really wretched soul, or we can put David Guetta on permanent Ecstasy.

# assume we get worlds sorted in ascending order.

makeworstoffhappier(world::World) = [(world[1] + 1);world[2:end]]

makebestoffhappier(world::World) = [world[1:end-1];(world[end] + 1)]Here is the weirdness. All our theories so far say that these two actions

julia> act(sort(genworld()), [makeworstoffhappier, makebestoffhappier])

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 181.54551586600817), (2, 181.54551586600817)]

(1, 181.54551586600817)

julia> act(

sort(genworld()), [makeworstoffhappier, makebestoffhappier], getutility_avg)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 2.2018468020290545), (2, 2.2018468020290545)]

(1, 2.2018468020290545)

julia> act(

sort(genworld()), [makeworstoffhappier, makebestoffhappier], getutility_cl)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 23.5264454626259), (2, 23.5264454626259)]

(1, 23.5264454626259)are equally good, whereas most people would say that improving the situation of the wretched one is more desirable.

Egalitarian Utilitarianism #

One way out of that problem is through Egalitarian Utilitarianism, where we assess how desirable a world is by looking not only at how much utility there is in it but also at how equally that utility is distributed among its receptacles. I am sure this is not the standard way of implementing that in practice, but anyway my version of Egalitarian Utilitarianism is to simply divide the sum total utility with the standard deviation:

getutility_ega(world::World) = sum(world) / std(world)Now it is clearly better to make the worst off happier than it is to make the best off happier, because while the sum total utility remains constant, the standard deviation is reduced:

julia> act(

sort(genworld()), [makeworstoffhappier, makebestoffhappier], getutility_ega)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 244.09869629867873), (2, 230.9551186679748)]

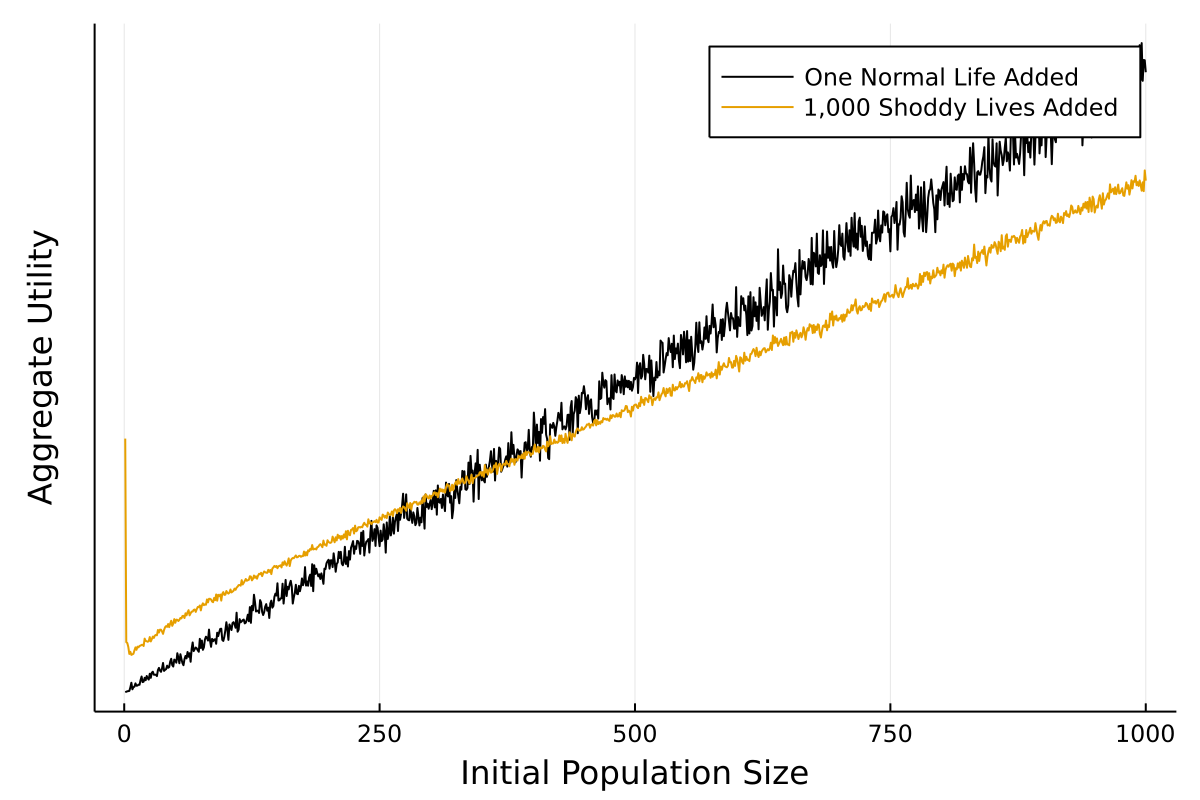

(1, 244.09869629867873)It is also better to add one normal life than it is to add one thousand lives that are barely worth living, however only above a certain threshold:

julia> act(genworld(), [addnormallife, addshoddylives], getutility_ega)

Got actions and consequences: [(2, 325.4768089647839), (1, 203.90928373375752)]

(2, 325.4768089647839)

julia> act(genworld(1000), [addnormallife, addshoddylives], getutility_ega)

Got actions and consequences: [(1, 1986.8005537494912), (2, 1642.2104443441826)]

(1, 1986.8005537494912)There is a trade-off here: the outcome depends on which population size we start out with. If we start out with a small population size, it is, according to the egalitarian utility function, better to add one thousand lives barely worth living, just like in Classical Utilitarianism, because since there are almost only the thousand in the world, the world is rather equal; however, when we begin with a large population, adding the one thousand produces great inequality.

getutilities_ega(action::Function) = getutility_ega.(a.(genworld.(1:1000)))

plot([getutilities_ega(addnormallife), getutilities_ega(addshoddylives)],

label = ["One Normal Life Added" "1,000 Shoddy Lives Added"])

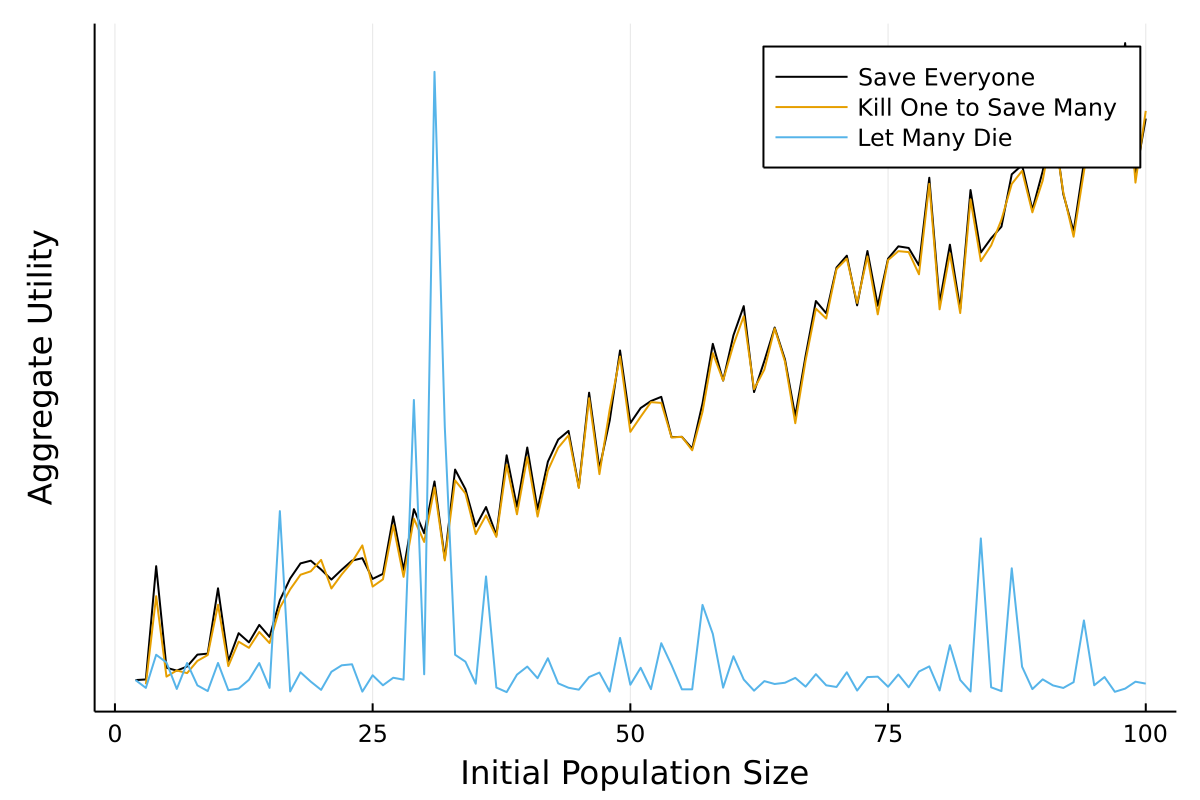

But when we run the Trolley Problem again, we get some pretty strange results:

result = runtrolley(getutility_ega, [donothing, killonetosavemany, letmanydie])

bar(result)

Why is it not always better to save everyone? That is because, sometimes, killing receptacles off can actually make the world more equal; in small worlds especially, the model is really sensitive to those kinds of changes. We can see this if we run 100 Trolley Problem simulations for different population sizes:

worlds = genworld.(1:100)

plot(getutility_ega.(donothing.(worlds)))

plot!(getutility_ega.(killonetosavemany.(worlds)))

plot!(getutility_ega.(letmanydie.(worlds)))

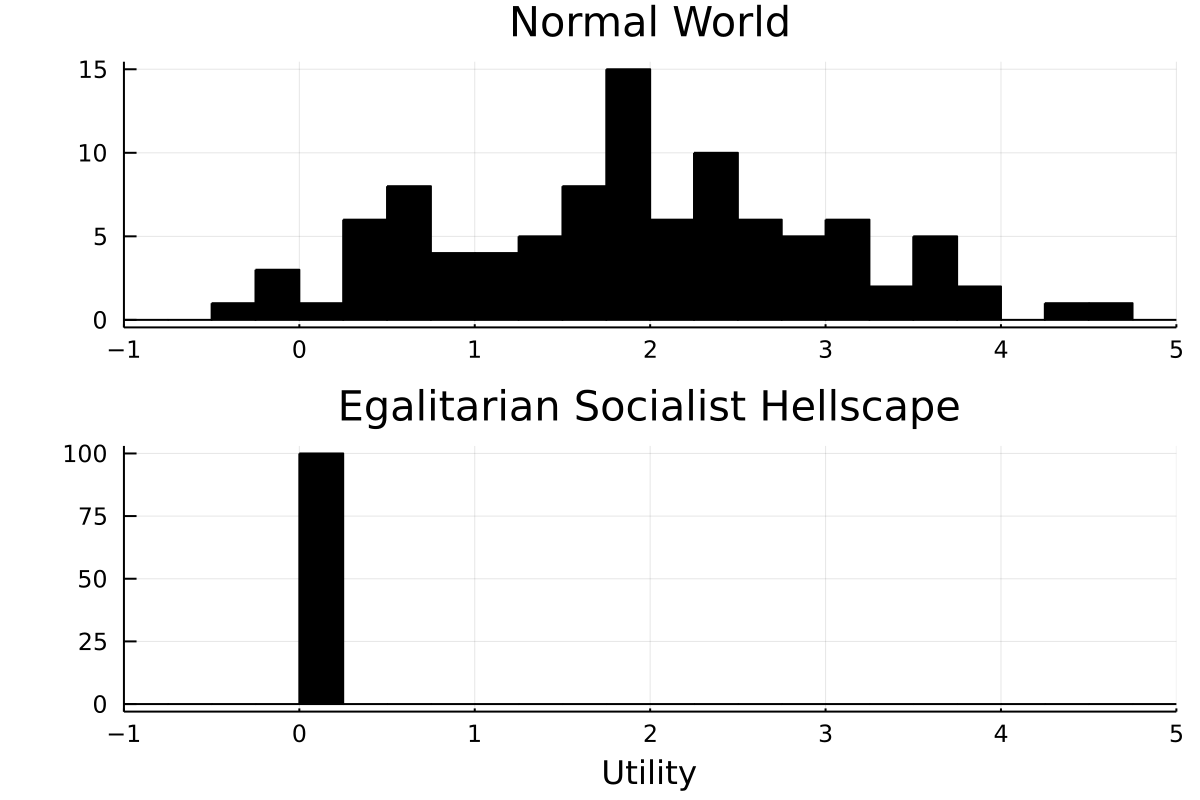

There is really high variance in the third action, because it always reduces the population to two. If these two have nearly the same utility, the world is very equal. In fact, this utility function says that a world with many similar lives barely worth living is better than a normal but less equal world. I suppose this is the utility function that some conservatives accuse some progressives of having and therefore what Winston Churchill referred to when he said that “[t]he inherent virtue of Socialism is the equal sharing of miseries”. We can model this, too:

using Distributions

genbarelypassablelife() = first(rand(Normal(0.1, 0.01), 1))

gensocialisthellscape(n::Int = 100) = map(

_ -> genbarelypassablelife(), zeros(n))If we plot the utility distribution

histogram(

[genworld(), gensocialisthellscape()], layout = (2, 1),

title = ["Normal World" "Egalitarian Socialist Hellscape"])

it seems obvious that the baseline world is preferable to the socialist hellscape. But in fact our egalitarian utility function prefers the latter by a wide margin:

julia> emptyworld = World(undef, 0)

julia> act(

emptyworld, [_ -> genworld(), _ -> gensocialisthellscape()], getutility_ega)

Got actions and consequences: [(2, 902.3415834900601), (1, 211.14893530485276)]

(2, 902.3415834900601)In Sum #

I want to be clear in pointing out that utilitarians are aware of and have responded to all these concerns; they have long since noticed the skulls. One excellent resource for utilitarian theory is the aforementioned utilitarianism.net. Another good introduction is reading the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s articles on consequentialism and the history of Utilitarianism.

Further variants of Utilitarianism include actual Egalitarian Utilitarianism, Negative Utilitarianism, Critical-Range Utilitarianism and Rule Utilitarianism, which does not alter the utility function but instead says that we should not choose the action that causes the greatest aggregate utility, but act according to the general rule that on average causes the greatest aggregate utility. Those are just a taste. There are many more distinctions cutting across various axes of Utilitarianism. Utilitarianism is not a church, it is a bazaar. I may visit it again in future, if I feel up for it.

Footnotes #

In fact, I was surprised at how useful this exercise was in revealing all the decisions you make when constructing a moral system; when doing so by thinking, discussing or writing alone, it is easy to let assumptions pass by unnoticed and unscrutinised. ↩︎

I have scrubbed the plotting code of some noisy details, which is why the plots generated by the code examples are not as polished as those shown in the images. Forgive me. ↩︎

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. OUP Oxford. ↩︎

Huemer, M. (2008). In defence of repugnance. Mind, 117(468), 899-933. ↩︎

I use the phrase “utility function” here in the philosophical sense, not in the programming sense of a helper function. ↩︎

Blackorby, C., Bossert, W., & Donaldson, D. (1997). Critical-level utilitarianism and the population-ethics dilemma. Economics & Philosophy, 13(2), 197-230. ↩︎

Broome, J. (2004). Weighing lives. OUP Catalogue. ↩︎