Uncommon Sensations: A Review of The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa

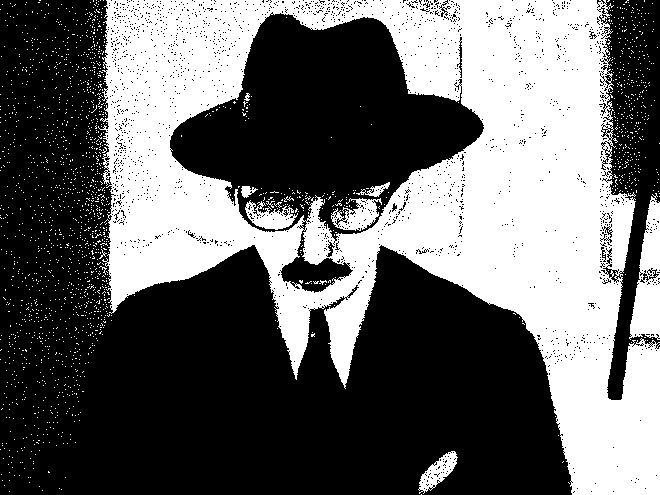

I bought The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa having read Forever Someone Else, a collection of poetry by the same author, the Portuguese modernist. The latter is great and beautiful. The former, a mishmash of short stories, plays, letters, essays, introductions, commentaries, manifestos, automatic writing, fragments and more, is weirder. Reading it is to be both awed and bewildered.

In a sentence: the prose writings of Fernando Pessoa are as beautiful in their descriptions of pure feeling as they are frustrating in their hopeless irrationality.

What do I mean by “irrationality”? I mean that while Pessoa sensed things and had some good intuitions, which led him to fertile grounds sometimes, he was never confident in the path he’d chosen, which at other times led him to latch on to any meaningless thing, to credulously accept absurdities and to engage in muddled reasoning. The Selected Prose is full of tendentious assertions, chains of reasoning like random walks, common words used in outrageously non-standard ways, fallacies, non-sequiturs, bluster and wishful thinking. These constitute failures of rationality in both senses of the word: failing to achieve a goal (to produce good art, presumably) and failing to arrive at true beliefs.

I’m not accusing Pessoa of inconsistency: he is inconsistent, but that’s a feature, not a bug. If you’ve heard anything about Pessoa, you’ll have heard that he wrote under >30 different “heteronyms” – a multitude of characters with their own names, styles, obsessions and backstories. It’s perfectly natural that these should contradict one another. My charge is that each of them also seems confused and self-contradictory themself.

Take for example him (as Dr. António Mora), having confidently declared that “humanity needs religious expression to discipline and organize societies” and identified the best religion as that which “is closest to Nature”, specifically “the pagan religion”, which “is, in the first place, polytheistic, even as nature is plural. Nature does not naturally appear to us as an ensemble but as a multiplicity of many different things. […] Now religion, since it comes to us as an outer reality, should agree with the fundamental characteristic of outer reality. That characteristic is the multiplicity of things. The first distinctive characteristic of a natural religion is, therefore, the multiplicity of gods” (Pessoa 2001, 148). What?! Because nature and religion both come to us as “outer realities”, and because nature comprises a variety of different things, we need a religion that comprises a variety of different gods? Why does religion need to reflect nature in this way? What’s so special about multiplicity that two so different things (the stuff of nature and gods) must necessarily share this feature? Why does multiplicity mean multiple gods and not multiple denominations or orders or saints or rituals or something else?

Or when in a letter to his aunt he describes, with total credulity, how he’s become a medium, how he communicates with phantom entities through automatic writing and how his friend has interpreted these writings for him (Pessoa 2001, 100–102): “[My friend explained] that the fact of writing numbers proves the authenticity of my automatic writing – that it’s not just autosuggestion but true mediumship.” And: “I’m beginning to have what occultists call ‘astral vision’, as well as what’s known as ‘etheric vision’. This is all very much in the early stages, but there’s no room for doubt.”

Or when he writes, in a fragment of an essay on millionaires: “No man has ever become a millionaire by hard work or cleverness. At the worst he became so by a vast and imaginative unscrupulousness; at the best by happy intuition in speculative circumstances. […] It is always a question of lottery tickets, though perhaps of having saved enough to buy them […]” (Pessoa 2001, 197). But this is either a truism or a fiction. It’s a truism if you take him to mean that any man who became a millionare might not have done so had he been unlucky enough. It’s a fiction if he meant that hard work and cleverness didn’t play important roles in determining who did or did not become a millionaire.

This element presents a barrier for anyone who’s allergic to bad epistemic habits. Is there a way out? Maybe a better strategy, instead of getting annoyed at those bad habits, is to read the thing as a satire on irrationality. After all, wasn’t satire invented to expose bad reasoning? Isn’t there humour to be found in Pessoa’s occasionally ridiculous fumbling about? Didn’t Pessoa himself use irony and exaggeration – I mean consciously?[1]

Consider for example the following passage on the artist-audience relationship: “Art is the highest and most subtle form of sensuality. The relations between the artist and his public are analogous to those of a man and woman in sexual intercourse […] That’s why the ardent aesthete is generally a sexual introvert.” (Pessoa 2001, 238). Read it supposing Pessoa’s in earnest. Then read it as satire. Doesn’t it work better as a send-up of anguished young artist-men?

Another advantage of this strategy is that it makes those instances where one of Pessoa’s heteronyms lionises another of his heteronyms – for example when Thomas Crosse compares Alberto Caeiro to Walt Whitman, writing of the former that he’s “so novel that it is sometimes hard to conceive clearly of all his novelty” (Pessoa 2001, 51) – appear less pathetic and more amusing (for if this is not satire, it’s sockpuppetry avant la lettre). Or I. I. Crosse (Pessoa 2001, 55): “Álvaro de Campos is one of the very greatest rhythmists that there has ever been. Every metric paragraph of his is a finished work of art.”

Or take The Anarchist Banker (Pessoa 2001, 167–96), a dialogue where a wealthy banker claims to be a perfectly sincere and consistent anarchist. Having initially cast his lot with the other anarchists, he understands that it is impossible for them to help others, so he embarks on a project to help the only person he can: himself. Of course there’s some irony in this. But you get the feeling that the banker, though mistaken, is at least supposed to be intelligent. What it really is is one man credulously following another as he reasons his way off an Iberian promontory. “‘Help them? I’ve never helped others, for that would infringe on their freedom, which is likewise against my principles. […] Why criticize me for doing my duty of freeing as many people as I could [that is, himself only]? Why not criticize those who didn’t do their duty [that is, save their own selves]?’”

The book’s compiler and translator, Richard Zenith, helpfully prefaces each excerpted work with some context. Introducing Erostratus: The Search for Immortality – an essay on (literary) immortality – he describes how motivated reasoning guided Pessoa’s thinking and writing: “As a young man Pessoa was convinced that fame was just around the corner. At the age of twenty-four, even before publishing any poems, he had already announced […] the coming of a poet who would dethrone Luís de Camões from his post as Portugal’s Greatest Writer. […] Toward the end of his life, Pessoa began to realize that fame was not liable to visit him this side of the grave. And so, good student of philsophy that he was, he drew a distinction between fame and immortality […] True genius, he contended, can never be recognized in its own lifetime” (Pessoa 2001, 203–4).

Now I only thought of this strategy after I’d finished the book, but perhaps it wouldn’t’ve mattered if I did. Trying to read The Selected Prose as a satire is, I think, a doomed venture. One, because irony has lost something when you know it’s unintentional. Two, because the implied author takes the shape it takes. You can’t will yourself to change it any more than you can will yourself to love somebody. Or, I suppose it is possible to will oneself to change a belief. But it seems hard and not worth it in this case.

Yet The Selected Prose is by no means a bad book. Pessoa was half deluded hysteric, and also half genius. Like a migrating bird, he emerged from the desert at times to arrive at places of real fertility. His redeeming quality is his ability to intuitively describe sensations. His genius is threefold.

First, it lies in the imagery he provokes. Second, it lies in the allegories beneath that imagery. Third, it’s in the sentences that give the imagery its colour.

These things, when they appear, as well as the more numerous more abstract passages, come to us against the backdrop of a rapidly modernising Lisbon, businessmen rushing about as trams noisily rattle by, the colossal Atlantic and what lies beyond and, most of all, dimly lit rooms furnished only with bookcases and small desks on which rests letter paper and inkstands. (For a book of prose, this one is comparatively devoid of scenery. Nature appears only in its abstract, capitalised version. Even the fiction is all dialogue and monologue.)

Permeating all this is a feeling of isolation or exile not unlike the one you find in the prose works of Gerald Murnane. Pessoa and Murnane were both born into a kind of isolation, though where Murnane conditioned his work on the view that he’s an exile from his native land (this being something like “the world that exists in one’s mind when one reads certain books or dwells on certain memories”), Pessoa seems to have held that view only sometimes; at other times, and to his detriment, he looked for home in every corner of the world he knew.[2]

So yes, plenty of irrationality. But isn’t that a small price to pay for the other half? Isn’t the book full of works and parts of works that avoid or transcend that difficulty?

We can for example turn to The Mariner – Pessoa’s only completed play – for a passage that shows both his isolation and his craftsmanship (Pessoa 2001, 28–29):

THIRD WATCHER Don’t talk like that. Just tell your dream, start telling it again … Don’t talk about how many can hear … We never know how many things really live and see and hear … Go back to your dream … The mariner. What did the mariner dream of? …

SECOND WATCHER (in a softer voice, very slowly) He began by creating landscapes; then he created cities; then he created streets and cross streets, one by one, sculpting them out of the substance of his soul – street by street, neighbourhood after neighbourhood, out to the sea walls of the wharfs, where he then created the ports … Street by street, and the people who walked them or gazed down at them from their windows … He began to know some of the people, at first just barely recognising them, but then becoming familiar with their past lives and their conversations, and he dreamed all this as if it were mere scenery to delight the eyes … Then he traveled, with his memory, through the country he’d created … And thus he created his past … Soon he had another previous life … In this new homeland he already had a birthplace, places where he’d grown up, and ports from where he’d set sail … He began to acquire childhood playmates, and then friends and enemies from his youth … It was all different from what he’d actually lived. Neither the country, nor its people, nor even his own past were like the ones that had really existed … Must I continue? It’s so painful to tell it! … Now, because I’m telling it, I’d rather be telling you about other dreams …

THIRD WATCHER Continue, even if you don’t know why … The more I hear you, the more I stop belonging to myself …

FIRST WATCHER But is it really a good idea for you to continue? Should every story have an end? But keep talking anyway … It matters so little what we say or don’t say … We keep watch over the passing hours … Our task is as useless as Life …

SECOND WATCHER One day, after a heavy rain that blurred the horizon, the mariner got tired of dreaming … He felt like remembering his true homeland …, but he couldn’t remember anything, and he realised it no longer existed for him … The only childhood he could recall belonged to the homeland of his dream; the only adolescence he remembered was the one he’d created … His entire life was the life he’d dreamed … And he realised he could never have had any other life … For he could remember none of its streets, none of its people, and not one motherly caress … Whereas in the life he thought he’d merely dreamed, everything was real and had existed … He couldn’t even dream, couldn’t even conceive, of having had any other past the way everyone else, for a moment, is able to imagine … O sisters, sisters … There’s something, I don’t know what, that I haven’t told you … something that would explain all this … My soul makes me shiver … I’m hardly aware of having spoken … Talk to me, shout at me, so that I’ll wake up and know that I’m here with you and that certain things really are just dreams …

Or see how António Mora, in his essay on Neopaganism, makes sentences that sing (Pessoa 2001, 151):

That rebellious Christians such as Pater and Swinburne called themselves neopagans when there was nothing pagan about them except the desire to be pagan is excusable, since there’s a certain logic in applying an impossible name to an absurdity. But we, who are pagans, cannot use a name that suggests that we are somehow “modern” about it, or that we came to “reform” or “reconstruct” the paganism of the Greeks. We came to be pagans. Paganism was reborn in us. But the paganism that was reborn in us is the same paganism there always was: submission to the gods, and justice on Earth for its own sake.

A scholar of paganism is not a pagan. And a pagan is not a humanist: he’s human. What a pagan most appreciates in Christism is the common people’s faith in miracles and saints, rituals and celebrations. It is the “rejected” part of Christism that he would most readily accept, if he would accept anything Christian. Any “modern paganism” or “neopaganism” that can understand the mystic poets but not the feast days of saints has nothing in common with paganism, because the pagan willingly admits a religious procession but turns his back on the mysticism of St. Theresa of Ávila. The Christian interpretation of the world disgusts him, but a celebration at church with candles, flowers, songs, and then a festival – he sees these as good things, even if they’re part of something bad, for these things are truly human, and are the pagan interpretation of Christianity.

Or take Bernardo Soares’s description of experiencing art or doing philosophy or perhaps feeling compassion from The Book of Disquiet (of which The Selected Prose contains excerpted passages) (Pessoa 2001, 290):

Every time I go somewhere, it’s a vast journey. A train trip to Cascais tires me out as if in this short time I’d traveled through the urban and rural landscapes of four or five countries.

I imagine myself living in each house I pass, each chalet, each isolated cottage whitewashed with lime and silence – happy at first, then bored, then fed up. It all happens in a moment, and as soon as I’ve abandoned one of these homes, I’m filled with nostalgia for the time I lived there. And so every trip I make is a painful and happy harvest of great joys, great boredoms, and countless false nostalgias.

And as I pass by those houses, villas, and chalets, I also live the daily lives of all their inhabitants, living them all at the same time. I’m the father, mother, sons, cousins, the maid, and the maid’s cousin, all together and all at once, thanks to my special talent for simultaneously feeling various and sundry sensations, for simultaneously living the lives of various people – both on the outside, seeing them, and on the inside, feeling them.

Pessoa’s failing is in judgment and inference: in judgment, because he is bad at evaluating possibilities using evidence in light of his goals, and in inference, because he either fails to account for evidence, or accounts for it badly. His success is in his creativity and openness: in creativity, because he is able to find possibilities that others haven’t thought of, and in openness, because he will pursue them past the point where others would have (usually, but not always correctly) ruled them out.

For some reason, Pessoa’s poetry – with its equally allegorical and beautifully expressed imagery – doesn’t suffer from the same problem as his prose. I think that’s because it’s blurrier and more cryptic. The prose works best when it deals with intuitive sensation, like poetry does. It does poorly when it deals with facts and ideas. It works well when it explores, but badly when it discerns or judges.

Maybe prose and poetry put different demands on the writer. The poet intuits something and expresses it so the reader intuits an analogous thing. It’s up to the reader to complete the creative act by interpreting and analysing the intuition. But the writer of fiction needs to do more: he or she must also guide the reader through the interpretation of the thing being expressed, a task which requires good sense and judgment.[3]

Any true poet looks for beauty where no one else has found it; the great ones have discovered unusually rich veins which only they are capable of mining. Fernando Pessoa was a true poet; he was right to think that there’s alpha to be found[4], only wrong to look for it in magic and sham spirituality. In the end one of the more beautiful passages in the book is a poem (by Álvaro de Campos) which Zenith has inserted to give context on Pessoa’s so-called astral communications (Pessoa 2001, 92):

I don't know if the stars rule the world

Or if tarot or playing cards

Can reveal anything.

I don't know if the rolling of dice

Can lead to any conclusion.

But I also don't know

If anything is attained

By living the way most people do.

References #

Footnotes #

When we read a piece of Pessoa’s fiction, there’s (1) the narrator in the text itself, (2) the breathing author, the man named Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa born on June 13th 1888, and (3), between those, as Wayne C. Booth showed us, the implied author – the almost-Pessoa we construct in our minds when reading the text. The breathing Pessoa probably did not set out to write pure satire, but maybe the implied Pessoa did. ↩︎

And I should mention that he expresses this beautifully in his poem about the Tagus river (Pessoa 2013, 36–37). ↩︎

There are authors who can do both of these things – they become great fiction writers – and others who can do only one of the two – they become poets or non-fiction writers. Or so I may claim if I were in a categorical, unnuanced mood. ↩︎

Cf. lsusr’s description of (financial) alpha: “Hundred-dollar bills lying on the sidewalk are called ‘alpha’. Alpha is a tautologically self-keeping secret. You can’t read about it in books. You can’t find it on blogs. You will never be taught about it in school. ‘You can only find out about [alpha] if you go looking for it and you’ll only go looking for it if you already know it exists.’” ↩︎