The Literary Technique of Recapitulation

Both historically and within Sonata Theory the term recapitulation (German, Reprise) suggests a postdevelopmental recycling of all or most of the expositional materials […] The recapitulation delivers the telos of the entire sonata – the point of essential structural closure, the goal toward which the entire sonata-trajectory has been aimed.[1]

– James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy

When I first began teaching myself musical composition through the books of Ernst Toch, Arnold Schönberg and Johann Joseph Fux, I was often struck by the parallels that exist between musical form and form in the other linear arts, arts like poetry and fiction. I thought of this again the other day when I read the final pages of a short story by Pierre Michon. The story reminded me of two things, first a novella, The Life of Joseph Roulin, that appears earlier in the same collection of stories and then one of the greatest books by my favourite author, Gerald Murnane’s Tamarisk Row. It reminded me of both of these because all three works had in common their ending with breathless, lyrical passages that recalled one by one all the major motives and images that had appeared in the works up to that point. I think of this technique as akin to the recapitulation in music, the final section (excluding the optional coda) in some musical forms, most famously the sonata, where all the themes are repeated one by one in the key of the Tonic.

I have written previously of the idea that meaning is connection, that we carry with us and interpret the world using networks of meaning and that the more nodes a thing can be connected to in this network, the more meaningful that thing is to us; to borrow a phrase from Baruch Spinoza, “the more things an image is joined with, the more often it springs into life”[2]. I wrote that this model would help explain “why younger people (who have had less time to form these meaning-connections) often have less sophisticated taste in art than adults (because sophisticated art relies on context and knowledge and is usually not on its own as immediately pleasurable or stimulating as popular art; sophisticated art needs things to latch on to; the minds of younger people contain fewer meaning-nodes for it to latch on to)” and “why there is a perceived need in any narrative to tie up all the loose ends, in other words to connect the themes, characters or events that have appeared in the narrative”.

Now I have learned that John Gardner got there before me:

It is this quality of the novel, its built-in need to return and repeat, that forms the physical basis of the novel’s chief glory, its resonant close. […] What moves us is not just that characters, images, and events get some form of recapitulation or recall: We are moved by the increasing connectedness of things, ultimately a connectedness of values. Coleridge pointed out […] that increasingly complex systems of association can give a literary work some of its power. When we encounter two things in close association […] we tend to recall one when we encounter the other. […] If the first time our hero meets a given character it occurs in a graveyard, the character’s next appearance will carry with it some residue of the graveyard setting. […] Even at the end of a short story, the power of an organized return of images, events, and characters can be considerable. Think of Joyce’s “The Dead”. In the closing moments of a novel the effect can be overwhelming.[3]

The recapitulation technique serves multiple functions in literature:

- By recalling all motives in quick succession and without pause, the narrative gathers momentum and can reach a climax.

- By putting all motives in relation to one another, the network of meaning becomes more tightly connected, the motives form a cluster and each motive supports the others even as it is supported by them.

- By putting all motives in relation to one another, there is a sense in which there are no more relations to uncover; the text’s promise has been fulfilled; there is a feeling of closure.

In The Life of Joseph Roulin, we follow the proletarian postman of that name of whose family Vincent Van Gogh painted innumerable portraits when they lived on the same street in Arles in Provence towards the end of the nineteenth century. The two became close friends and the postman, so I’ve read, was fiercely loyal to the painter, who was over a decade his junior. The story ends by imagining Roulin’s death three years after the painter’s, him having collapsed at the side of a country road, “a little road that snakes its way above the great gulf, a yew tree at its end, a cypress”.[4] In the final paragraph, the narrator connects the novella’s major motives, themes and images to the philosophical problem of beauty:

Who can say what is beautiful and as a result, amongst men, is deemed worthless or worthwhile? Is it our eyes, which are the same, Vincent’s, the postman’s, and my own? Is it our hearts, which a trifle can seduce, which a trifle can dismiss? Is it you, young man sitting with your hat placed next to you chez Ambroise Vollard, talking animatedly about painting with beautiful women? Or you, paintings roosting in Manhattan, merchandise whose enlightened fads nourish the dollars, doubtlessly drawing them nearer to God as well? Is it you, Browning? Perhaps it’s you, Old Captain topped in blue, looking at a little heap of Prussian blue fallen on a road; it’s you, white beasts, learned and mute, whose very volumes we caress far from here on rue des Récollettes, who know exactly what three francs is worth; it’s you, crows flying up above that no one can buy, no one can command, which do not speak and are only eaten during the worst famines, whose feathers even Fouquier wouldn’t want in his hat, dear crows to whom the Lord gave wings of matte black, a cry that cracks, the flight of a stone, and from the mouth of His servant Linneaus came the imperial name Corvus corax. It’s you, roads. Trees that die like men. And you, sun.[5]

This passage “ties the bag together” as the Swedish expression puts it: the subject matter of the entire novella has gone into it and, resting at the centre, touching all those other things, is the question how can one tell what is beautiful? The paragraph begins with sentences of medium length, a walking rhythm, but then speeds up as phrases get shorter and semicolons replace periods before finally slowing down in the final three sentences, which are brief but peaceful and spacious. The slackening of the pace together with the completed repetition of all the previously appearing motives makes us feel that we have arrived somewhere familiar, perhaps home; it is the peaceful feeling of repose that the Tonic key generates in music. And thus does Michon use the recapitulation technique for each of its functions.

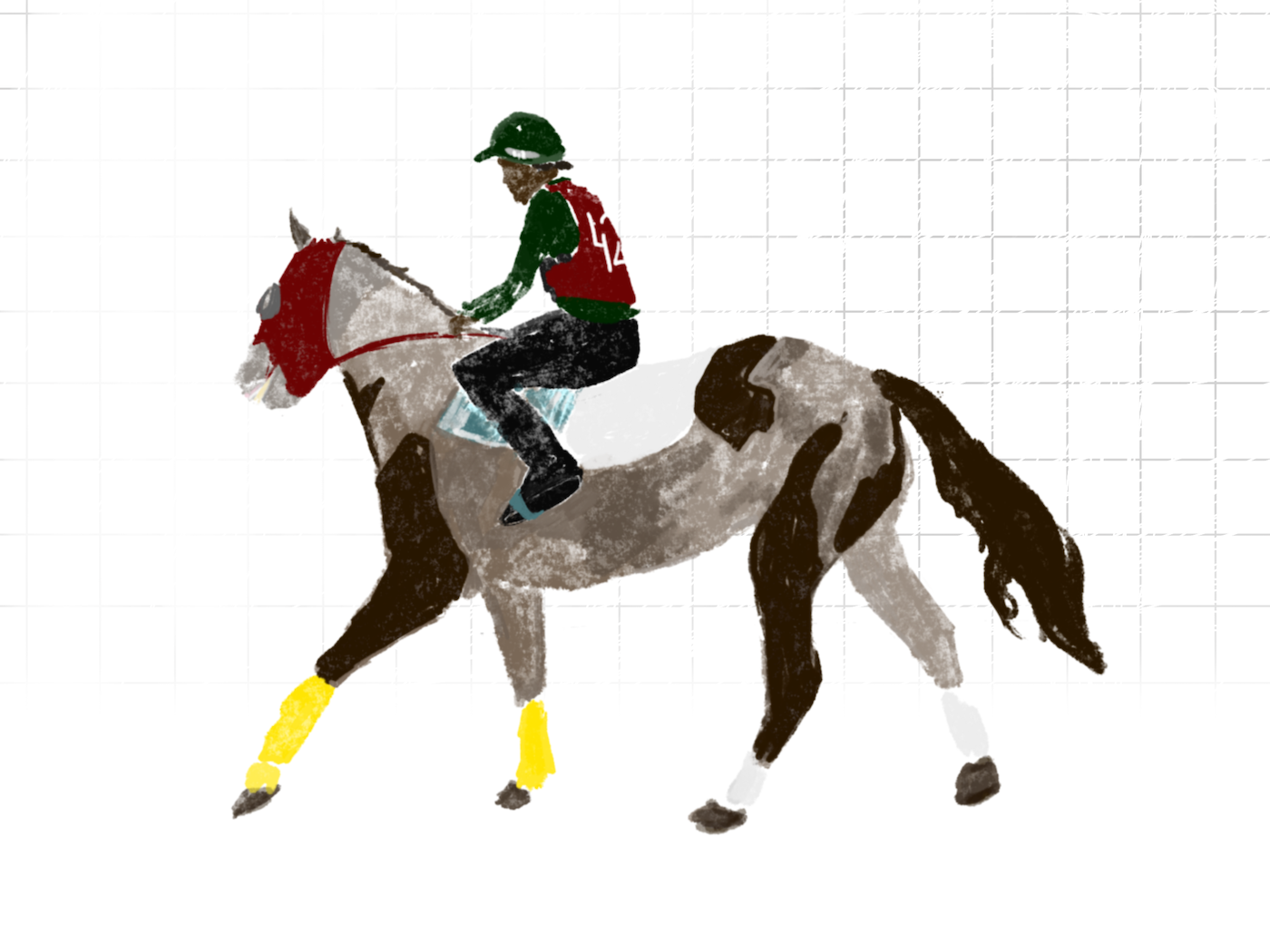

Tamarisk Row, though also a work of fiction from the second half of the twentieth century[6], is quite different in subject matter and style. Quoting the back cover, it is “an unsparing evocation of a Catholic childhood in a Victorian country town in the late 1940s. Clement Killeaton transforms his father’s obsession with gambling, his mother’s piety, the cruelty of his fellow pupils and the mysterious but forbidden attractions of sex, into an imagined world centred on horse-racing, played in the dusty backyard of his home, across the landscapes of the district, and the continent of Australia.”[7] Many of its central themes and images – glass marbles, horse-racing, colour, plains, grasslands, ground-dwelling birds, Catholicism, the forbidden pleasures, the female sex – many of these are important themes also in other works of his; all of them are invoked in the final passage of the book, which passage bears the heading “The Gold Cup race is run”.

“Over the years”, Murnane writes in the foreword to the 2007 Giramondo edition, “several readers have told me that they consider ‘The Gold Cup race is run’ an example of so-called stream-of-consciousness prose. It is no such thing. What is now[8] the last section of the book consists of five very long compound sentences, each comprising a main clause and numerous subordinate clauses, together with a description of part of a horse-race. These six items are interwoven, so to speak. […] In due course, the five sentences come to an end, one after another. The race-commentary, however, does not quite come to an end. The very last words of the book are the words of the race-caller as the field of horses approaches the winning-post.”[9]

I should add that said race-commentary concerns the race of fifteen horses, each seemingly invented by Clement Killeaton and each carrying racing colours that represent one of the book’s subject matters, as is made clear near the book’s middle point. Number fifteen, for example, is Tamarisk Row and carries “green of a shade that has never been seen in Australia, orange of shadeless plains and pink of naked skin” representing “the hope of discovering something rare and enduring that sustains a man and his wife at the centre of what seem to be no more than stubborn plains where they spend long uneventful years waiting for the afternoon when they and the whole of a watching city see in the last few strides of a race what it was all for”.[10]

Reproduced below is the Gold Cup race passage in full. (I have also tried to separate the six items and present them individually; you can find the result of that labour in this footnote[11].) Notice how Murnane uses signposts to indicate where a new sentence-part begins: the first sentence has many parts beginning with verbs in present participle form; the second with the conjunction while; the third with the adverb where; the fourth with various positional prepositions like past and over; and the fifth with the third person singular pronoun he followed by a verb in the indicative form. Notice also how the interwoven sentences and the absence of any punctuation propels the text to a climax, how once again all of the main motives in the book are combined and connected to one another, and finally how, as the sentences resolve one by one, several times ending by mentioning the phrase tamarisk row, we arrive at a clear cadence:

A boy suspects all along that he may only be pushing a handful of marbles without knowing where they might finish while a rider lifts his arm again and again and brings the whip down savagely and the horse Sternie who was once the hope of the Jew the shrewdest punter of all goes on slowly improving his position in a field of plodding country gallopers he sees a racecourse where silks of a certain red promise a man that he might soothe at last the restless cock between his legs when he looks out above the roof-tops of an inland city that he has never understood while he spends years training for the day when he comes from behind to win a famous foot-race in the straight now it’s still anybody’s race Lost Streamlet is the leader but Passage of North Winds is coming out after him studying pictures in the Sporting Globe of horses a few furlongs from home in races that have already been decided while people in the crowd gape at their fancies bunched indecisively near the rails and the horse Clementia comes down the outside rail alone and almost unnoticed and his owner wonders why he never guessed that he was training a champion where white silk may stand for the soul of a man with God on his side far across the great northern plains that he has never ventured into he tries for years to discover a place where protestant and pagan girls walk naked and never care who sees them Hills of Idaho is looming up suddenly Veils of Foliage is not to be denied shoving stones along a dirt track between crude fences of chips of wood while a woman stands with her ear pressed against a crackling wireless set and the horse Skipton that her husband has backed for hundreds of pounds leaves the rails and begins his run from absolute last in the Melbourne Cup field where orange reminds someone in the crowd of the gritty footpaths and yards in the city that he always returns to past the heart of Australia that he admits he has no claim to he searches for years for a backyard where a pure girl knows an innocent game that he and she will never tire of Hare in the Hills is coming into the picture Proud Stallion Den of Foxes is in the thick of things and Captured Riflebird is trying to get through straining his muscles and gasping for breath trying to come from last in a foot-race while the filly Mishna draws clear at the furlong and two or three men in the crowd glance at each other but so discreetly that no one would guess they were about to bring off one of the greatest betting plunges ever planned in Australia where every shade of blue hints at the awesome mysteries of Our Lady and the Catholic Church over the woods and fields of England filled with birds that breed and nest without fear in sight of the people there he sees for years above his calendar a land of somber colours where saints and holy people go gracefully past on journeys of their own past the furlong and Hills of Idaho shows out in front but challenges are coming from everywhere listening through the wall of his bedroom to learn what his parents are planning while the horse Silver Rowan with a few huge strides asserts his claim and a man whose ancestors once built a stone castle with a tower that looked out over miles of green country that they never wanted to leave knows that Ireland is about to be avenged at last where pale gold is meant to be the colour of a delicate freckle hidden beneath a woman’s dress on a secret part of her body between the dark hills of Europe that the gypsies found their way out of at last he reaches the very borders of a land where great herds of cattle graze on shining prairies and men return across great distances to find their sweethearts Lost Streamlet is refusing to give in Veils of Foliage Hare in the Hills is swooping on them wandering through a maze of streets in a city whose map he could never draw while the people of Melbourne are talking about Bernborough a mighty horse from the north who is on his way down from Queensland winning race after race and Augustine Killeaton solemnly tells his son that a greater horse than Phar Lap has appeared in the land where the least glimpse of a certain pale green may mean that a man has discovered a country that no one else will ever see beyond the enormous prairies of America that will be remembered forever in films and hillbilly songs he comes as near as he dares to a green-gold land where creatures set out from intricate cities over plains that may take a lifetime to cross or may suddenly close over the travellers and all trace of their journeys a mighty wall of horses Hills of Idaho is about to be swamped and Springtime in the Rockies sees daylight at last watching plains and hills and more plains rushing past the window of a train or a furniture van while the professional punter Len Goodchild and his inner circle appear in the crowd on yet another provincial racecourse and a knot of people follows them to see what they fancy where a rare silver sometimes appears like the rain above a coast where a man first dreamed of following the races even further than the desolate land between Palestine and Egypt and he believes he has reached for once a different city although it still seems familiar Veils of Foliage Hare in the Hills Springtime in the Rockies emerges from nowhere and never able to foresee the end of it all far out on a plain three or four horses are bunched together about to take up the positions that will be preserved for years to come but their riders jerk their arms or thrust with their heels or raise and lower their whips with a graceful action as though they cannot hear the screaming crowd and know nothing of the thousands of pounds depending on them and do not realise that any one of them with a last desperate effort might lift his mount and himself into the one position that will make them famous but are already figures in a faded photograph showing the finish of a great race in which one horse triumphed and the rest were soon forgotten by all but a few faithful followers and where a colour that no one has yet been able to copy onto any silk jacket the colour of the most precious milk-stones might tell of a traveller who can find his way back from lands it is hopeless to try to cross in the direction of the district of Tamarisk Row he sees what may still not be the last place of all yet he knows at last that he will never leave Tamarisk Row and Tamarisk Row is coming home when it’s all over.[12]

Footnotes #

Hepokoski, J., & Darcy, W. (2006). Elements of sonata theory: Norms, types, and deformations in the late-eighteenth-century sonata. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Spinoza, Ethics (Vp13d). ↩︎

Gardner, J. (2010). The art of fiction: Notes on craft for young writers. Vintage. ↩︎

Michon, P. (2013). Masters and Servants. Yale University Press. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

I assume, though, that this technique is far older than the two works I am using to illustrate it here, and it surely has its roots in the kind of repetition and enumeration that was already common in ancient texts. ↩︎

Murnane, G. (2008). Tamarisk Row. Giramondo Publishing. ↩︎

In the first edition, this section appeared earlier in the book, after the editor had insisted and Murnane, at that time an unpublished writer, had yielded. ↩︎

Murnane, G. (2008). Tamarisk Row. Giramondo Publishing. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

- (i) A boy suspects all along that he may only be pushing a handful of marbles without knowing where they might finish while (ii) studying pictures in the Sporting Globe of horses a few furlongs from home in races that have already been decided, (iii) shoving stones along a dirt track between crude fences of chips of wood, (iv) straining his muscles and gasping for breath trying to come from last in a foot-race, (v) listening through the wall of his bedroom to learn what his parents are planning, (vi) wandering through a maze of streets in a city whose map he could never draw, (vii) watching plains and hills and more plains rushing past the window of a train or a furniture van (viii) and never able to foresee the end of it all far out on a plain three or four horses are bunched together about to take up the positions that will be preserved for years to come.

- (i) A rider lifts his arm again and again and brings the whip down savagely and the horse Sternie, who was once the hope of the Jew, the shrewdest punter of all, goes on slowly improving his position in a field of plodding country gallopers (ii) while people in the crowd gape at their fancies bunched indecisively near the rails and the horse Clementia comes down the outside rail alone and almost unnoticed and his owner wonders why he never guessed that he was training a champion (iii) while a woman stands with her ear pressed against a crackling wireless set and the horse Skipton that her husband has backed for hundreds of pounds leaves the rails and begins his run from absolute last in the Melbourne Cup field (iv) while the filly Mishna draws clear at the furlong and two or three men in the crowd glance at each other but so discreetly that no one would guess they were about to bring off one of the greatest betting plunges ever planned in Australia (v) while the horse Silver Rowan with a few huge strides asserts his claim and a man whose ancestors once built a stone castle with a tower that looked out over miles of green country that they never wanted to leave knows that Ireland is about to be avenged at last (vi) while the people of Melbourne are talking about Bernborough, a mighty horse from the north who is on his way down from Queensland winning race after race, and Augustine Killeaton solemnly tells his son that a greater horse than Phar Lap has appeared in the land (vii) while the professional punter Len Goodchild and his inner circle appear in the crowd on yet another provincial racecourse and a knot of people follows them to see what they fancy (viii) but their riders jerk their arms or thrust with their heels or raise and lower their whips with a graceful action as though they cannot hear the screaming crowd and know nothing of the thousands of pounds depending on them and do not realise that any one of them with a last desperate effort might lift his mount and himself into the one position that will make them famous but are already figures in a faded photograph showing the finish of a great race in which one horse triumphed and the rest were soon forgotten by all but a few faithful followers.

- (i) He sees a racecourse where silks of a certain red promise a man that he might soothe at last the restless cock between his legs, (ii) where white silk may stand for the soul of a man with God on his side, (iii) where orange reminds someone in the crowd of the gritty footpaths and yards in the city that he always returns to, (iv) where every shade of blue hints at the awesome mysteries of Our Lady and the Catholic Church, (v) where pale gold is meant to be the colour of a delicate freckle hidden beneath a woman’s dress on a secret part of her body, (vi) where the least glimpse of a certain pale green may mean that a man has discovered a country that no one else will ever see, (vii) where a rare silver sometimes appears like the rain above a coast where a man first dreamed of following the races (viii) and where a colour that no one has yet been able to copy onto any silk jacket, the colour of the most precious milk-stones, might tell of a traveller who can find his way back from lands it is hopeless to try to cross.

- (i) When he looks out above the roof-tops of an inland city that he has never understood (ii) far across the great northern plains that he has never ventured into (iii) past the heart of Australia that he admits he has no claim to (iv) over the woods and fields of England filled with birds that breed and nest without fear in sight of the people there (v) between the dark hills of Europe that the gypsies found their way out of at last (vi) beyond the enormous prairies of America that will be remembered forever in films and hillbilly songs (vii) even further than the desolate land between Palestine and Egypt and (viii) in the direction of the district of Tamarisk Row, he sees what may still not be the last place of all.

- (i) While he spends years training for the day when he comes from behind to win a famous foot-race in the straight, (ii) he tries for years to discover a place where protestant and pagan girls walk naked and never care who sees them, (iii) he searches for years for a backyard where a pure girl knows an innocent game that he and she will never tire of, (iv) he sees for years above his calendar a land of somber colours where saints and holy people go gracefully past on journeys of their own, (v) he reaches the very borders of a land where great herds of cattle graze on shining prairies and men return across great distances to find their sweethearts, (vi) he comes as near as he dares to a green-gold land where creatures set out from intricate cities over plains that may take a lifetime to cross or may suddenly close over the travellers and all trace of their journeys, (vii) he believes he has reached for once a different city although it still seems familiar, (viii) yet he knows at last that he will never leave Tamarisk Row.

- (i) Now it’s still anybody’s race Lost Streamlet is the leader but Passage of North Winds is coming out after him (ii) Hills of Idaho is looming up suddenly Veils of Foliage is not to be denied (iii) Hare in the Hills is coming into the picture Proud Stallion Den of Foxes is in the thick of things and Captured Riflebird is trying to get through (iv) past the furlong and Hills of Idaho shows out in front but challenges are coming from everywhere (v) Lost Streamlet is refusing to give in Veils of Foliage Hare in the Hills is swooping on them (vi) a mighty wall of horses Hills of Idaho is about to be swamped and Springtime in the Rockies sees daylight at last (vii) Veils of Foliage Hare in the Hills Springtime in the Rockies emerges from nowhere (viii) and Tamarisk Row is coming home when it’s all over.

Murnane, G. (2008). Tamarisk Row. Giramondo Publishing. ↩︎