Simulations of Diversity Hiring

Edit 2023-11-12: I have revised this post to (1) replace the old introduction, which did not add much, with a brief summary, and (2) improve the clarity of a few sentences.

Many organisations aim to increase the diversity of their members along various axes. I expect that, for large organisations, and without affirmative action, efforts to improve diversity will take a long time (decades) to reach their desired end results, especially for low-growth organisations.

On the surface, hiring with diversity in mind may seem like a simple problem with a simple solution: the way to increase minority representation in an organisation is to hire more people from minorities and to retain as many employees from minorities as possible. But of course it’s much more complicated than that. How many people you can hire depends on how much your organisation is growing, and on its attrition rate (the percentage of employees who leave the company each year). How many people from minority groups you can hire depends on the proportion (and absolute number) of people from minority groups among potential hires. Attrition rates are different in different subpopulations. And so on.

(There are also likely regional differences here. Japanese companies, for example, seem to be much less willing than U.S. companies to employ people with an uncertain impact, even if their expected impact is higher than the safer choice. That is because Japanese workers are often employed for life, so false positives are more costly, whereas US workers can more easily be fired. Also in Japan, it seems hiring is often the responsibility of the human resources department alone, such that it will adopt a low-risk strategy in order to avoid blame for bad hires. On the other hand, there is also an association between employment protections and women workforce participation generally, though of course correlation is not causation, and the reverse relationship was found for temporary contracts.)

Being curious about when we could expect big tech companies to reach something like gender parity, I created a Metaculus question asking just that. There are no predictions yet as the question has only been open since late yesterday evening.

Addendum 2023-11-12: Two years later, the community prediction for when the first FAAMG company will have a workforce that is 50% or fewer men has a median of 2098, with a 50% confidence interval from 2052 to “will not happen before 2100”. However, the distribution is somewhat bimodal: there is a fair bit of probability mass around 2040 to 2050 and a bunch of probability mass on “will not happen before 2100”.

Simulations #

I developed a simple model to simulate how various strategies in diversity hiring might affect the constitution of a set of companies’ workforces.

(Obvious warnings here are that this is not peer-reviewed research by a domain expert and that the model makes several simplifying assumptions, which I will outline later. I should also point out, if it wasn’t clear already, that I am not making any judgements about the value of diversity, equity and inclusion work.)

The model works like this. It supposes there are 100 companies, each of which employs 500 workers. It then steps forward 25 years one by one, and at each year:

- each employee has some chance of leaving their current employer;

- each company may grow (or not) to need a larger (or smaller) workforce;

- each company hires from a pool of surplus workers to both fill the empty roles left by those who quit, and to accommodate their growth (if they grew);

- the employees who quit their jobs join the pool of surplus workers;

- there is an infinite elasticity of substitution, meaning male and female workers are indistinguishable apart from different attrition rates; and

- new graduates join the pool of surplus workers, to bring it back to its original size.

As you will have noticed by now, to make things simple, the model is concerned only with one dimension of diversity – gender of the binary sort (sorry, enbies). It also assumes

- that there is a fixed number of companies;

- that there is a fixed pool of surplus workers;

- that the attrition rate does not change over time or depend on an employee’s tenure;

- that each company begins with a workforce consisting of 30% women and 70% men;[1] and

- that there is a fixed gender ratio among new graduates – specifically, 47% of new graduates are women and 53% men.[2]

Sometimes companies grow, and sometimes they shrink. Sometimes employees are more likely to quit, and sometimes less, and this likelihood can be different for women and for men. Sometimes there are many potential workers available for hire, and sometimes there are few. Sometimes a company hires fairly, and sometimes unfairly. These factors are not assumed, but varied in different simulation runs.

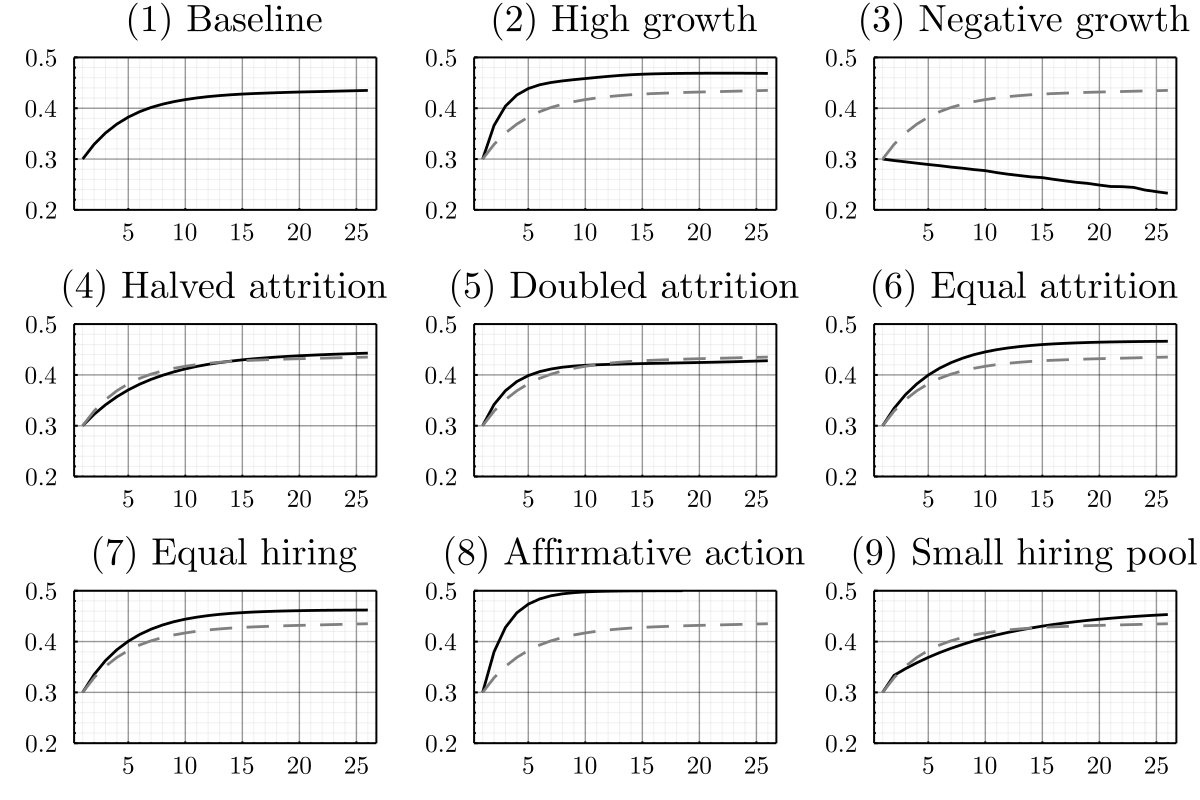

Here are the results of the nine runs I made. They show the average proportion of women in a company over time.

Looking at each of these in turn:

- This is our baseline scenario. Here, we assume that hiring is fair as far as gender is concerned, which actually seems to be the case in the industry.[3][4] In other words, the ratio of women to men that a company hires equals the ratio of women to men that are available for hire. We also assume that women have an attrition rate of 15.4% and men one of 11.8%.[5] We assume that the pool of surplus workers is large enough never to be a constraint, numbering one million, in other words that there is no hiring friction in the labour market. And we assume that all companies grow by ten percent each year. The companies reach an equilibrium around 43% women, which is lower than that of the new graduates (47%) because women are more likely to leave their jobs each year than men are.

- In this extremely realistic (hmm, hmm) scenario, all companies grow by 50% each year. This actually ends up being really good for diversity, because new graduates are more diverse than the initial workforces.

- With negative growth (all companies shrink by ten percent each year) we see the opposite effect. They are not in a position to hire new employees, and with women’s higher attrition rate the existing workforce gets less and less diverse over time.

- Here, we halve the attrition rates for both women and men. Interestingly, this does slightly worse than the baseline for about 15 years, and then does slightly better. In other words, it is slower to reach its equilibrium, because fewer people quit each year which means fewer people will be hired. But its equilibrium, when it is reached, is closer to the 47/53 split seen in new graduates, because the only thing preventing companies from reaching that near-parity is the difference in attrition rate, which is of course smaller in absolute terms when the rates have been halved for both genders.

- For the same reasons, if we double the attrition rates for both genders, we get the opposite effect.

- Now assume that women had the same attrition rate as men. We now reach an equilibrium at 47% women, which perfectly mirrors the ratio in new graduates (although we do so more slowly than in the high-growth scenario).

- What if, instead of equalising women and men’s attrition rates, we made sure to hire exactly 50% women and 50% men, so long as the pool of potential workers allow it? This ends up being really similar to (6), but again we are held back by women’s being more likely to leave their employer.

- In this scenario, the proportion of women the companies hire is inversely related to the proportion of women they are currently employing. So if a company has 40% women, they will try to make 60% of new hires women, etc. This gets the companies to gender parity in about ten years. Though in my experience, companies are hesitant to do this, because – assuming the talent distribution is identical for potential hires who are women and for those who are men – it will necessarily involve lowering standards for the underrepresented group and raising them for the overrepresented group.

- In the final run, we keep the affirmative action strategy from (8) but reduce the pool of surplus workers to a mere thousand. That’s ten potential hires per company each year. In other words, we have introduced hiring friction in the labour market. You’ll see a “knee” two years in – that is because the initial pool of surplus workers, which reflects the 47/53 split of new graduates, has been depleted, so to speak, and largely replaced by people who were previously employed (the 30/70 split). More importantly, diversity growth is severely hampered as there just aren’t enough women in the workforce to keep up with the companies’ demand. That is probably one reason why the FAAMG companies, which are enormous, have trouble reaching the diversity goals they have set for themselves.

Addendum 2023-11-12: I recently came across a new and very interesting gender diversity paper by Shasha Wang: STEMming the Gender Gap in the Applied Fields: Where are the Leaks in the Pipeline? It suggests much of the sorting happens prior to any hiring decision. “Closing gender skill gaps upon exiting high school reduces female under-representation by 67% in applied-stem majors and 31% in applied-STEM occupations. Removing the preference for female-dominated workplaces reduces female under-representation by 29% in applied-STEM majors and 85% in applied-STEM occupations. Equalizing wage offers in STEM sectors has a smaller effect (3% in majors and 10% in occupations).”

One takeaway from all this is that it is a lot easier to increase diversity for a company that is growing. That means we can expect scaling startups to be better able to increase diversity than companies like Oracle, for example. We should also take care when comparing newer companies with older companies – if a company grew quickly when the industry was less diverse, it will have a large workforce that is quite uniform, and that takes a long time to change through hiring alone.

But I think my main takeaway here is that it will be a long road ahead if the tech industry is ever to reach gender parity, assuming it does not start implementing some sort of affirmative action. Given reasonable assumptions about company growth, attrition rates and demographics of companies and graduates today, even if there is no bias in hiring, it still takes many years to approach parity.

Footnotes #

This was the estimate in the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s Diversity in High Tech report. The number may be larger in Northern Europe. For example, Spotify in 2018 had a workforce with 39% women. At the end of 2020, they were at 44%, but since they have an unusual focus on diversity, I think the earlier figure is more in line with the Northern European tech industry in general. ↩︎

This seems to be the case for STEM in Sweden these days. (Universitetskanslersämbetet, published in SCB Jämställdhet.) ↩︎

Parasurama, P., Ghose, A., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2020). Gender and Race Preferences in Hiring in the Age of Diversity Goals: Evidence from Silicon Valley Tech Firms. Available at SSRN 3672484. ↩︎

Palmgren, A. (2021). Gender discrimination in the labour market: A meta-analysis of field experiments, researching gender discrimination in the labour markets hiring process. ↩︎

I don’t remember the source but the general attrition rate for the software industry seems to be about 13.2%. It also seems that the attrition rate is about 30% higher for women than for men. Using those numbers as well as the estimates for the distribution of women and men in the current workforce, I came up with these attrition rate estimates – 15.5% for women and 11.8% for men. They seem reasonable to me. ↩︎