On Amorality

“I must make an admission”, Ivan began. “I never could understand how it’s possible to love one’s neighbours. In my opinion, it is precisely one’s neighbours that one cannot possibly love. Perhaps if they weren’t so nigh … I read sometime, somewhere about ‘John the Merciful’ (some saint) that when a hungry and frozen passerby came to him and asked to be made warm, he lay down with him in bed, embraced him, and began breathing into his mouth, which was foul and festering with some terrible disease. I’m convinced that he did it with the strain of a lie, out of love enforced by duty, out of self-imposed penance. If we’re to come to love a man, the man himself should stay hidden, because as soon as he shows his face – love vanishes.”

– Fyodor Dostoevsky (2004)

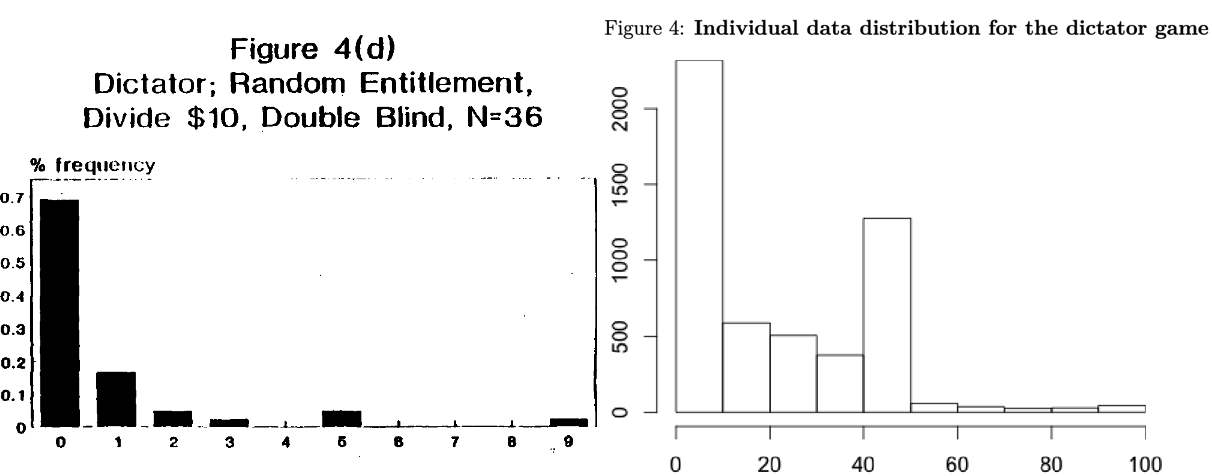

It won’t surprise you to learn that, with the exception of the most saintly and selfish among us, types of which Alyosha and Ivan are as good examples as any, and though it leaves mostly unexplained where moral movements like abolitionism, republicanism, liberalism, women’s rights, animal rights and gay liberation came from or why norms change at all really (we’re always taking moral philosophy and applying it to norms, whereas maybe we should be taking norms and applying them to moral philosophy?[1]), and because one, subjects in the dictator game when their identities are unknown to the other subjects, all of whom I picture glancing warily at the kind researcher behind their back, rarely share even half of their given pot with the counterparty, and hardly ever more than that (Hoffman et al. 1994; Tisserand, Cochard, and Le Gallo 2015), and because two, subjects in the dictator game when their identities are unknown not just to one another but even to the experimenter, a group of people, let’s remember, that by necessity includes many who are more conscientious, more generous and more compassionate than the average person (assuming we have a statistically representative sample, at least), and surely suspicious of being the victim of some ploy or trap, still tend to leave, in a feat of sublime courage and imagination, the counterparty with absolutely nothing at all (Hoffman et al. 1994; Tisserand, Cochard, and Le Gallo 2015) –

– a shocking effect which, though it’s weaker in less industrialised nations (Engel 2011), owing perhaps to a “my friends and family assist” mindset quite different from our new “the state provides” mindset (for us Europeans, it’s not necessary to think of one another, it’s only necessary to pay taxes), and though it’s weaker among older people (Engel 2011), owing to I don’t know what, may even be too bullish on altruism seeing as you can’t design experiments that blind their subjects to God and the unshakeable sense that someone, somewhere is watching, and which for that reason is probably accurately summarised by the philosopher Michael Huemer when he says that “[w]hen no one can see them, then the great majority of people revert to selfishness”, I think perhaps, in most people, self-interest dominates pure altruism, but norms dominate both[2]; only that’s not to say that humans are amoral, it’s only to say that humans can’t imagine morality outside a community and that, in accordance with a “moral philosophy influences norms influence behaviour” causal pathway[3], where moral philosophy has no effect at all on most people’s behaviour when conditioning[4] on norms[5], our way of realising our altruistic impulses aren’t by acting on them directly but by turning them into norms and then acting on those.

References #

Footnotes #

That’s a half-baked thought. I guess what I mean is that any model of meta-ethics, or any account of practical ethics, benefits from incorporating norms, because norms are such an important part of human moral behaviour. I like this about constructivist accounts. They don’t say “here’s the Good, now let’s evaluate how humans behave according to that standard”, they say something like “here’s how humans (and other animals) behave, from this we infer that this or that thing is the Good, now let’s evaluate how humans behave according to their own standards”. ↩︎

If this is true, is it bad?

There’s an open question about whether acting altruistically is a good way of doing good. For example, Zvi Mowshowitz notes that altruism, which he defines as the belief that “the best way to do good yourself is to act selflessly to do good”, is (surprise) a core idea in effective altruism, and one that he himself strongly disagrees with. I think the idea there is that there’s a lot of self-interested behaviour – think somebody who takes employment as a nurse, say, because they need to pay rent – that has positive benefits for others. I think you’d also need to believe that people who follow their own interest in some sense do more or more successfully than people who have others’ interests in mind. (This is me speculating on what such an argument would look like – Zvi doesn’t actually spell out his reasons for thinking so.)

I strongly disagree with Zvi’s strong disagreement. First, because altruism has an advantage when it comes to doing good: all else equal, it’s easier to reach some goal X by optimising for X directly than by optimising for some other goal Y which may cause X as a side-effect. Second, because I think people are by default pretty selfish (see the dictator games referenced in the post), which must have made sense from an evolutionary perspective, but evolution didn’t optimise for the stuff we mean when we talk about “doing good”. Third, because I think effective altruists, per capita, do more good (on my view of good) than any comparable group that I know of, in part thanks to their relative selflessness. Fourth, because I think there’s a sense in which selfish acts that happen to be good for others are morally worse than unselfish acts that are (and are intended to be) good for others.

It’s most probably true that some effective altruists are too selfless – that is, to the point that they burn out or their mental health deteriorates – but effective altruists in general are way out there on the tail end of the selfishness-selflessness spectrum; and if we were to learn that there was to be a general outbreak of selflessness somewhere tomorrow, we should probably think that’s for the better. ↩︎

This is a simplification, because norms also affect people’s moral thinking (confirmation bias, etc.), and I suppose sometimes behaviour influences either (e.g. some impressive person’s example can change our perspective on a moral issue). ↩︎

Conditioning in the statistical sense, that is. Another way of putting this is that, if you already know which norms a person adheres to, information about that person’s moral philosophy (to the extent that they have one) doesn’t much help you predict their behaviour. ↩︎

This seems like one aspect where there’s a population-level difference between effective altruists and leftists (though there are important exceptions, of course, like Matt Bruenig’s policy work): whereas most effective altruists take moral philosophy and use it to determine their actions, most leftists (and rightists) take moral philosophy and use it to change (or safeguard) societal norms. That’s an outrageous generalisation, of course. ↩︎