Interview with Lucia Coulter: Lead Exposure, Effective Altruism, Progress in Malawi

Background #

Lead, the most abundant of heavy metals, has been used by humans for thousands of years; there are records of lead poisoning in the ancient world, where it was used in water pipes and earthenware vessels.[1] Still today, lead exposure is a significant global problem, especially among poorer people in the developed world and in the developing world generally.[2] Even exposure to small amounts of lead can have significant and often irreversible health effects, especially in children, including impaired cognition, hyperactivity, cardiovascular disease and so on.[3][4][5] Attina & Trasande estimates the yearly cost of lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries to be nearly one trillion dollars, well over one per cent of world GDP when the study was made.[6] One of the main sources of lead exposure in children today is lead-based paint.[7]

Lucia Coulter is a co-founder and co-director of the Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP), a non-profit working to reduce lead exposure via lead-based paint. Lucia was kind enough to answer some questions of mine about lead exposure generally and LEEP’s work specifically; these answers are reproduced with only very minor edits below. (As a declaration of interest, I should note that I have donated a small sum to LEEP, though only after Lucia had sent me her answers.)

The Problem of Lead Exposure #

ERICH: Given the outrage that followed the Flint water crisis some years ago, it might be surprising to some that, as you write in your introductory post on the Effective Altruism Forum, “815 million children have blood lead levels [at] a sufficient level for neurodevelopmental effects and reduced IQ [and] one in three children are currently affected by lead poisoning to some degree”. Why has lead exposure been so neglected?

LUCIA: I think there are a few reasons for this but probably one of the most important is that this widespread chronic lead poisoning affecting one in three kids is relatively invisible. The effects include neurodevelopmental problems like reduced intelligence, behavioural problems, reduced educational attainment, reduced income, and cardiovascular disease later in life. Anyone experiencing these problems or seeing children experience these problems isn’t going to know that they are the result of lead exposure. And as a result, lead exposure is not going to seem like a priority problem to research or address.

ERICH: How does the evidence for the lead paint to blood lead levels (BLLs) pathway look? Is there any risk that measures of lead levels in paint is a bad proxy for lead levels in humans?

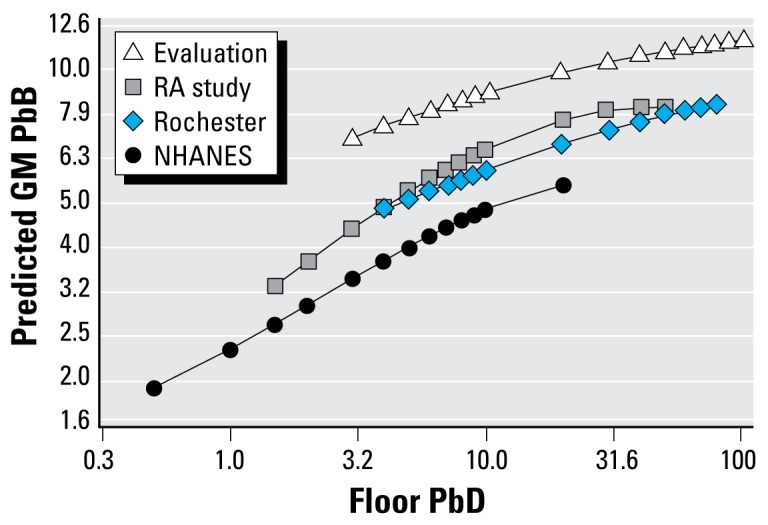

LUCIA: There is good evidence that lead in paint on walls is associated with raised blood lead levels in humans. In the U.S. lead paint is thought to account for up to 70% of elevated blood lead levels[8] and U.S. children in houses with lead paint were found to be almost ten times more likely to have elevated BLLs than children in similar housing without lead paint[9]. The condition of the paint seems to be an important predictor of blood lead levels, not just the lead content of the paint.[10] This relationship between lead in paint and blood lead levels appears to be mediated via lead in house dust, which makes sense because it’s the lead paint dust and flakes that get from the floor onto children’s hands and into their mouths. This nice graph from Dixon shows the relationship between house dust and BLLs.[11]

What’s more uncertain is how good a proxy lead levels in paint is for blood lead levels in low income countries. This has not been studied extensively. In many countries the only data we have is the amount of lead in the paint available on the market. It’s not obvious how to relate this to the amount of lead paint actually on the walls in homes and other areas around children. It’s also not obvious what the actual relationship is between lead paint on walls and lead dust on floors. This makes it difficult to quantify the impact of lead paint on blood lead levels in children in low income countries.

Despite this difficulty quantifying the impact and despite most of the evidence being from the U.S. and other high income countries, there is some evidence from low income countries for an association between lead paint and and raised blood lead levels, for example in Nepal[12], Benin[13], Nigeria[14], Egypt[15], South Africa[16], Brazil[17], and India[18][19][20].

Founding LEEP #

ERICH: What, in brief, does LEEP do to reduce lead exposure?

LUCIA: First we identify countries where we expect there to be a lot of lead paint use. Then we carry out paint sampling studies and basic market analysis to verify if this is the case. If we find that there is a lot of lead paint on the market then we share this information with the health ministry, regulatory authority, and other stakeholders. We explain why lead paint is a problem and that the solution is effective regulation (they may need to introduce new regulation or start enforcing existing regulation). We then support them in the process by bringing together stakeholders and providing technical advice. We also work directly with the local lead paint manufacturers to provide any technical advice needed for reformulation and help them access non-lead ingredients. We expect that enforcement of lead paint regulation and support with reformulation and compliance will lead to less lead paint on the market, less lead paint in homes and schools, and therefore less childhood lead exposure.

ERICH: You founded LEEP together with Jack Rafferty. Could you say a few words about your background? What brought you to effective altruism generally and to lead exposure as a cause area specifically?

LUCIA: I’ve been on board with the basic ideas of effective altruism for many years (in fact, ever since I first read Famine, Affluence and Morality by Peter Singer when I was 12!). I became more seriously involved when I was at university and co-ran the Cambridge chapter of Giving What We Can. I volunteered for EA-related organisations throughout my time at medical school and during my first two years working as a doctor.

After my second year working as a doctor it felt like a good time to try something new and more impactful. I had some friends who had started Charity Entrepreneurship incubated charities and thought it sounded like a very high impact option, as well as a great opportunity to learn a load of new cross-applicable skills in a short space of time.

Lead exposure reduction was recommended in the Charity Entrepreneurship incubation program. It appealed to me for all the normal EA reasons – huge scale problem, neglected, and potentially very tractable. I also thought that my medical background could be advantageous, especially when working with health ministries and health-related academics.

ERICH: So this is your first time running a non-profit. How has the experience been thus far?

LUCIA: Yes, it’s my first time running a non-profit. The experience has been great! I’m very happy to be doing something that has the potential for really significant impact. It’s incredibly rewarding when we make progress – for example when the Malawi Bureau of Standards agreed to start implementing lead paint regulation. And it’s a lot of fun working with my co-founder Jack, our volunteers, and our partners. Charity Entrepreneurship has also made a big difference – their support from the incubation program to now has helped with pretty much every aspect of our work.

For me the biggest challenge is the psychological one of never having 100% certainty that what we’re doing will work or will have the impact that we’re expecting. I do remind myself of the “expected value” argument, but I think because of my personality I just don’t really enjoy the uncertainty that comes with this type of work.

ERICH: Could you expand a little on how Charity Entrepreneurship helped you prepare?

LUCIA: Firstly they provided a two-month full-time incubation program, which I went through (remotely) in the summer 2020. This was where I decided to work on lead exposure (which was an idea researched and recommended by Charity Entrepreneurship), where I paired up with my co-founder Jack, and from where we received our initial seed grant. During the program we learnt a huge amount of extremely relevant and practical material – for example, how to make a cost-effectiveness analysis, how to make a six-month plan, how to develop a monitoring and evaluation strategy, how to hire, and a lot more. Since then Charity Entrepreneurship has provided LEEP with weekly mentoring and wider support through the community of staff, previous incubatees, and advisors. I highly recommend checking out the Charity Entrepreneurship incubation program if anyone is interested!

LEEP’s Progress #

ERICH: Besides LEEP, there are also a few other organisations working in this space, notably Pure Earth. How does your work differ from theirs?

LUCIA: Pure Earth focuses on other sources of lead exposure, for example toxic hotspots caused by informal lead-acid battery recycling and lead-contaminated spices. We currently focus on lead paint, but would be open to targeting other sources of lead exposure if the evidence is strong enough for the sources being important and tractable to address.

IPEN is another international organisation working to reduce lead exposure from paint. They provide funding and guidance to local organisations advocating for lead paint regulation. We differ from IPEN because we generally work directly in countries that don’t have local organisations addressing the lead paint. We also have more of a focus on enforcement and follow up studies to track if regulation is having the intended impact of reducing lead paint on the market.

ERICH: What have you achieved in the nine months or so that LEEP has operated so far? You mention having prodded the Malawi Bureau of Standards (MBS) to start monitoring and regulating paint lead content, for example.

LUCIA: We carried out a paint sampling study that showed that solvent-based paint in Malawi contains high levels of lead. We shared these findings with the Health Ministry and Malawi Bureau of Standards and raised awareness with them of the effects of childhood lead exposure. As a result of the data and our meetings MBS has decided to start monitoring paint for lead content and enforcing lead paint regulation. They are planning to update their paint standards to a 90 ppm limit (the WHO and UN recommended limit) to make their standard more enforceable and are currently arranging a technical committee with lead paint manufacturers to agree on a transition timeline and deadline for compliance. We have also had engagement from the lead paint manufacturers and have met with them to identify barriers and offer our support with reformulation.

We have since run a paint sampling study in Botswana, which showed that household paint currently on the market is imported from South Africa (where there is lead paint regulation in place) and does not contain high levels of lead. We are currently running paint studies in Zimbabwe and Madagascar as well.

ERICH: So it sounds as if you’ve begun picking the low-hanging fruit by going to countries that are likely to have lots of lead-based paint, that you think are willing to listen and where no one else is doing similar work. Do you have any sense of whether it’ll be possible (or desirable – I guess at some point lead-based paint will be all but gone) to scale your operations up?

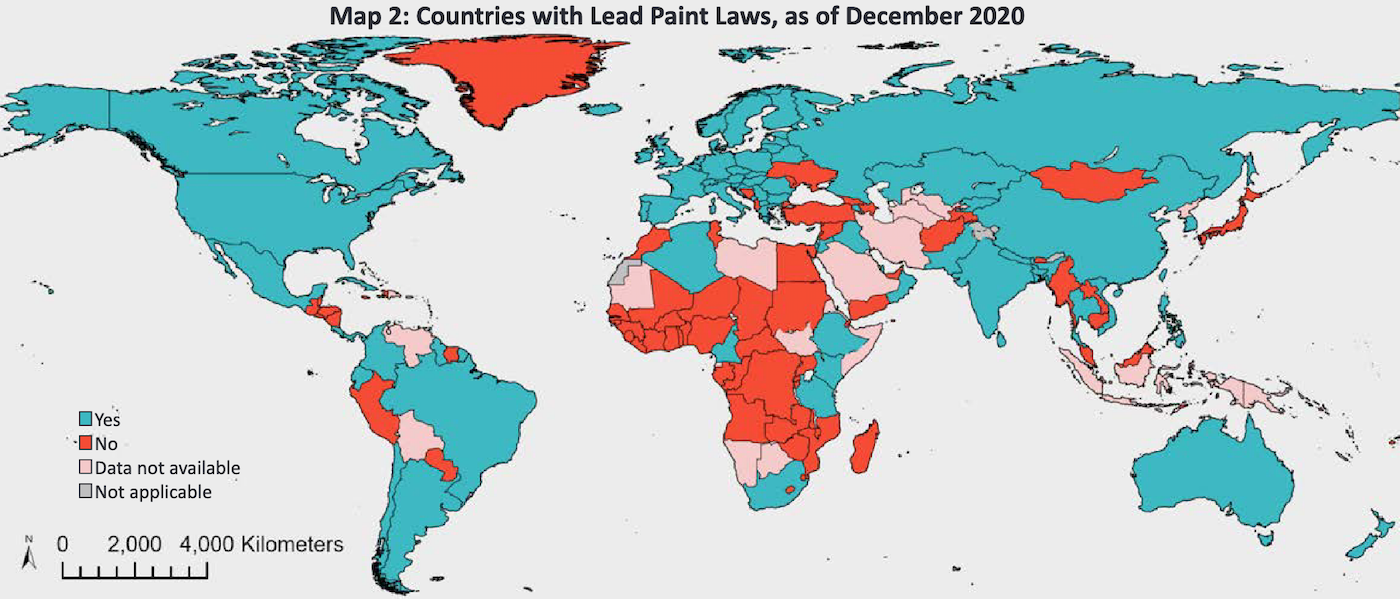

LUCIA: Yes, that’s right. In year two we plan to expand our operations to around three further countries with the aim of testing the effectiveness of our approach more quickly and improving it through iteration. Then, if we have sufficient evidence to suggest that what we’re doing is impactful and cost-effective we’d like to scale up rapidly. There are still over 76 countries yet to regulate lead paint, and many others that are yet to effectively implement their regulation. Most of these are likely to have a lot of lead paint on the market. Some do look like “low-hanging fruit”, but others are likely to be less tractable due to less receptive or unstable governments. The more quickly we can reduce the amount of lead paint being used in as many countries as possible the better, partly because in many potential target countries there are currently rapid increases in paint use and population growth.

Challenges and Opportunities #

ERICH: I found it interesting that lack of enforcement of standards, rather than lack of standards, seems to be the main problem, at least in Malawi. How come? Why were standards created in the first place if no one thought they were important to enforce?

LUCIA: It sounds like the lead paint standards were added because of an awareness of the public health implications of lead in paint. But it was explained to us that they were not enforced because it was not thought that there was any lead in paint. The understanding was that the use of lead in paint was an outdated technology that had naturally been phased out. So when we presented evidence showing that there is still a lot of lead in paint we were told it was a “wake up call” and that MBS would take action to address it.

ERICH: How likely is it that enforcement in Malawi becomes laxer again? What would it mean for LEEP’s cost-effectiveness if governments like Malawi’s were prone to “relapse”, so to put it?

LUCIA: This would reduce our cost-effectiveness so it’s important to us to keep the momentum going. One way we plan to do this is by running regular follow-up studies where we sample the paints on the market and measure the lead content. We can use this up-to-date information to encourage enforcement and compliance. However, the main cost to manufacturers is in the initial reformulation, so once they switch there is unlikely to be a major incentive to start adding lead again.

ERICH: From what I understand, you’ve communicated test results on paint lead levels mainly to the paint industry and to government officials and regulatory agencies. Do you think there is any potential value in bringing it to the local public, too, for instance via media? Or does that risk damaging relations with local industry and government?

LUCIA: We think this could be a useful approach because it would increase pressure on the manufacturers to reformulate and on the government to take the problem seriously. But at the moment it is being taken seriously and we’re seeing good progress working with MBS and the industry. So our current view is that it’s not worth the risk of damaging our relationships.

ERICH: David Bernard and Jason Schukraft discuss, as one area of uncertainty here, that there already seems to be “global momentum toward restrictions on the amount of lead that can be included in residential paint”. Does that seem true to you?

LUCIA: It is true that there is a global trend towards lead paint regulation, but this does seem to be due to active efforts to promote the change. In our cost-effectiveness analysis we assume that lead paint regulation would be implemented even without our input, but we would expect this to happen some time in the future (perhaps around eight years in Malawi). So our impact is a result of bringing the change forward in time. In the case of Malawi it would probably have taken someone else to carry out a paint study and bring the data to the attention of the government to cause any change. There hasn’t been any other activity in this area so we don’t think this would have happened in the near future without our input. Similarly, in Zimbabwe before our involvement there was no research into the problem of lead in paint and to our knowledge no efforts to advocate for regulation.

ERICH: What do you see as the biggest risks in LEEP’s work going forward?

LUCIA: One risk is that progress could stall in Malawi and we don’t reach the point of actually having reduced lead paint on the market within the next couple years. This could happen if the government or industry stops engaging with us and prioritising enforcement and compliance. So far engagement has been good and if momentum does slow there are other approaches to try like increasing pressure through the media and public. Another uncertainty is the extent to which our progress in Malawi is replicable in other countries. We’ll be able to get a better sense of that over the next year as we continue work in our other target countries.

ERICH: Though you focus on lead paint right now, I assume you’d be open to other ways of reducing lead exposure too, if they are effective. What other interventions do you think might be impactful beyond eliminating lead in paint?

LUCIA: This is a big open question of ours because there is such limited evidence about the importance of different sources of lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries.

Turmeric has been identified as an important source in Bangladesh[21] and there’s some evidence to suggest spices are a source in other countries as well[22]. An intervention here could be to sample spices in countries with a lot of spice use and high burdens of lead poisoning, analyse the lead content, then raise awareness of the problem, advocate for better enforcement of food safety regulations, and support changes in practices. This sort of approach could be taken with a number of different suspected sources, but would require sufficient evidence to suggest that if lead is identified in the suspected source it is actually likely to be causing significant exposure.

A different approach could be to start from scratch and fund source apportionment studies in countries with large burdens of lead poisoning to identify the most important sources. The drawback of this approach is that it is time-consuming and costly to run large high-quality studies to give good enough evidence that is representative of exposure in the country. But it would provide a very useful starting point to work out the best interventions to address the sources that are important in the country.

Footnotes #

Tong, S., Schirnding, Y. E. V., & Prapamontol, T. (2000). Environmental lead exposure: a public health problem of global dimensions. Bulletin of the world health organization, 78, 1068-1077. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. (2005). Lead exposure in children: prevention, detection, and management. Pediatrics, 116(4), 1036-1046. ↩︎

Navas-Acien, A., Guallar, E., Silbergeld, E. K., & Rothenberg, S. J. (2007). Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease—a systematic review. Environmental health perspectives, 115(3), 472-482. ↩︎

Attina, T. M., & Trasande, L. (2013). Economic costs of childhood lead exposure in low-and middle-income countries. Environmental health perspectives, 121(9), 1097-1102. ↩︎

My source here is the 2020 lead-based paint report by the United Nations Environment Programme, which states that “[d]ecorative paint for household use has been identified as the main source of children’s lead exposure from paints”. ↩︎

Levin, R., Brown, M. J., Kashtock, M. E., Jacobs, D. E., Whelan, E. A., Rodman, J., … & Sinks, T. (2008). Lead exposures in US children, 2008: implications for prevention. Environmental health perspectives, 116(10), 1285-1293. ↩︎

Schwartz, J., & Levin, R. (1991). The risk of lead toxicity in homes with lead paint hazard. Environmental research, 54(1), 1-7. ↩︎

Lanphear, B. P., Burgoon, D. A., Rust, S. W., Eberly, S., & Galke, W. (1998). Environmental exposures to lead and urban children’s blood lead levels. Environmental Research, 76(2), 120-130. ↩︎

Dixon, S. L., Gaitens, J. M., Jacobs, D. E., Strauss, W., Nagaraja, J., Pivetz, T., … & Ashley, P. J. (2009). Exposure of US children to residential dust lead, 1999–2004: II. The contribution of lead-contaminated dust to children’s blood lead levels. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117(3), 468-474. ↩︎

Dhimal, M., Karki, K. B., Aryal, K. K., Dhimal, B., Joshi, H. D., Puri, S., … & Kuch, U. (2017). High blood levels of lead in children aged 6-36 months in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: A cross-sectional study of associated factors. PloS one, 12(6), e0179233. ↩︎

Bodeau-Livinec, F., Glorennec, P., Cot, M., Dumas, P., Durand, S., Massougbodji, A., … & Le Bot, B. (2016). Elevated blood lead levels in infants and mothers in Benin and potential sources of exposure. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(3), 316. ↩︎

Ladele, J. I., Fajolu, I. B., & Ezeaka, V. C. (2019). Determination of lead levels in maternal and umbilical cord blood at birth at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos. PloS one, 14(2), e0211535. ↩︎

AbuShady, M. M., Fathy, H. A., Fathy, G. A., Fatah, S. A. E., Ali, A., & Abbas, M. A. (2017). Blood lead levels in a group of children: the potential risk factors and health problems. Jornal de pediatria, 93(6), 619-624. ↩︎

Mathee, A., Röllin, H., Levin, J., & Naik, I. (2007). Lead in paint: three decades later and still a hazard for African children?. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(3), 321-322. ↩︎

da Rocha Silva, J. P., Salles, F. J., Leroux, I. N., da Silva Ferreira, A. P. S., da Silva, A. S., Assunção, N. A., … & Olympio, K. P. K. (2018). High blood lead levels are associated with lead concentrations in households and day care centers attended by Brazilian preschool children. Environmental Pollution, 239, 681-688. ↩︎

Kalra, V., Sahu, J. K., Bedi, P., & Pandey, R. M. (2013). Blood lead levels among school children after phasing-out of leaded petrol in Delhi, India. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 80(8), 636-640. ↩︎

Patel, A. B., Belsare, H., & Banerjee, A. (2011). Feeding practices and blood lead levels in infants in Nagpur, India. International journal of occupational and environmental health, 17(1), 24-30. ↩︎

Patel, A. B., Williams, S. V., Frumkin, H., Kondawar, V. K., Glick, H., & Ganju, A. K. (2001). Blood lead in children and its determinants in Nagpur, India. International journal of occupational and environmental health, 7(2), 119-126. ↩︎

Forsyth, J. E., Weaver, K. L., Maher, K., Islam, M. S., Raqib, R., Rahman, M., … & Luby, S. P. (2019). Sources of blood lead exposure in rural Bangladesh. Environmental science & technology, 53(19), 11429-11436. ↩︎

Ericson, B., Gabelaia, L., Keith, J., Kashibadze, T., Beraia, N., Sturua, L., & Kazzi, Z. (2020). Elevated Levels of Lead (Pb) Identified in Georgian Spices. Annals of Global Health, 86(1). ↩︎