How I Make Dungeon Synth

Last week, on 30 December 2021, the great Milan-based dungeon synth label Heimat der Katastrophe released the fifth edition of the Dungeon Synth Magazine, a series of albums released on cassette tape, each comprising four tracks by four artists and four accompanying short stories printed in the tape booklet. The first track on this fifth release is by myself, under the moniker ICEWIND DALE. (I borrowed the name from the Dungeons & Dragons-based video game series.) The piece gets its title from the accompanying story, “A Distant Apocalypse” (henceforth ADA). You can listen to it here.

In this post I will outline my method for making dungeon synth, in the hope that it might inspire somebody else, with the obvious caveats that this is just one way of doing it and that I am far from the greatest or most experienced dungeon synth producer.

The general way of it is this. First I compose the thing in MuseScore. At some point I export that to a MIDI file and put it in Ableton Live, where I choose instruments, add effects and mix everything. Then follows a period where I go back and forth between writing notes in MuseScore and changing sounds in Live. When the thing near completion, I add ambience sounds in Live. Then I listen, change things, listen more and change more things until I am happy with it.

Composition #

The method I use to actually write notes is derived from Alan Belkin’s compositional method.[1] I do this in MuseScore – in other musical projects, I play instruments live, or try to play rather, but when I make dungeon synth, I compose purely on the computer. Here are the preparatory steps, where about half of the composing work is done:

- Make several varied sketches of musical ideas, things like brief motives or melodies or chord progressions. The more, the better.

- Select the most promising of these.

- Expand the chosen ideas into longer sketches, something that could be a small section in a final piece, ideally with several sketches for each idea.

- Select the passages that will make up the main themes and determine how to order them.

- Plan a beginning, climax and ending.

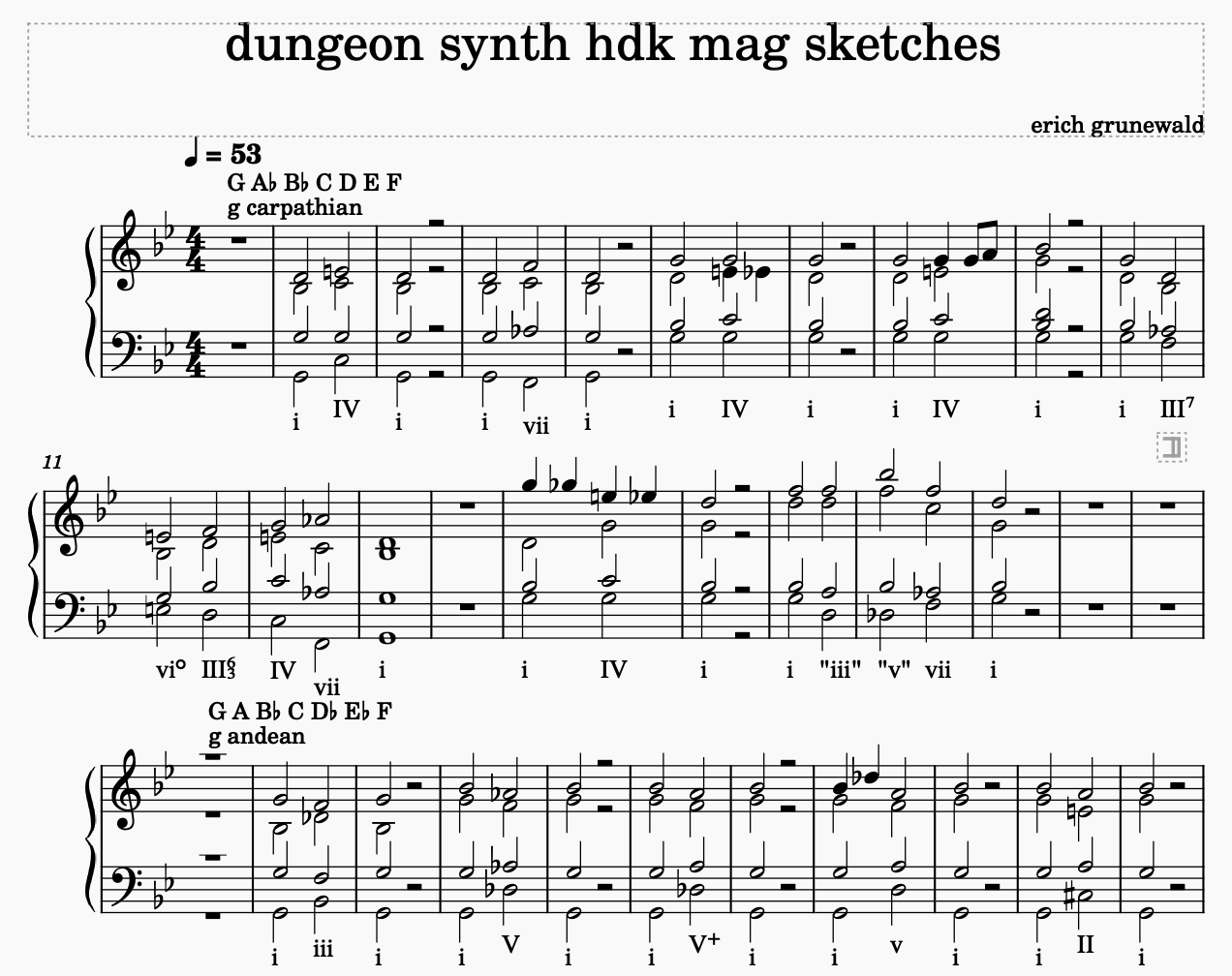

At this point, I probably will have written these sketches only in a single instrument, like a piano or an organ. Here are some harmonic sketches that I made for ADA:

(I write all my music in various synthetic scales, which I have rebaptised with more evocative names. I originally generated these scales via operations that Godfried Toussaint used in describing what he called Euclidean rhythms[2], and only then discovered that they already had names. What I call the Carpathian mode of the Montane scale is really Dorian ♭2, and what I call the Andean mode is the half-diminished. ADA is written in the Carpathian and Andean modes. I like writing in synthetic scales because of their inherent dissonance.)

Having finished the preparatory work, I move the selected passages to a new document and begin work on the final composition. I expand the passages to use more instruments (see the next section). I leave space for a beginning, an ending, planned repetitions and connective passages, and then gradually fill these with music. Most musical forms involve repetition, so there is actually less work to be done here than it might at first seem.

Musical form is recursive: larger forms are often constructed by combining smaller forms. They are boxes that contain other boxes that in turn contain further boxes. More atomic forms are simple phrases, brief musical passages that make some kind of sense on their own. Phrases are themselves made up of motives, which are even smaller units. I find that this is a useful framing, because problems are more easily solved when decomposed into smaller subproblems, and that is what this allows us to do with the problem of musical form. ADA is written in sonata form, with an introduction, two themes, a brief development and a recapitulation where the two themes are repeated with only minor changes. The first theme is in AA’A’’ form. The second theme is in ABA form. And these smaller segments are themselves made up of even smaller cells.

When writing music at this stage, I try not to invent new musical ideas or motives. There is enough material in the passages I already have. The final composition will be more unified if I base introductions, codas, transitions and everything else on the motives and ideas that are already there. It is easy to generate new variations of motives, for instance by changing the rhythm, shifting it to other beats, removing notes, adding ancillary notes, changing the order of notes, embellishing and ornamenting, adding upbeats, changing the harmony and so on.

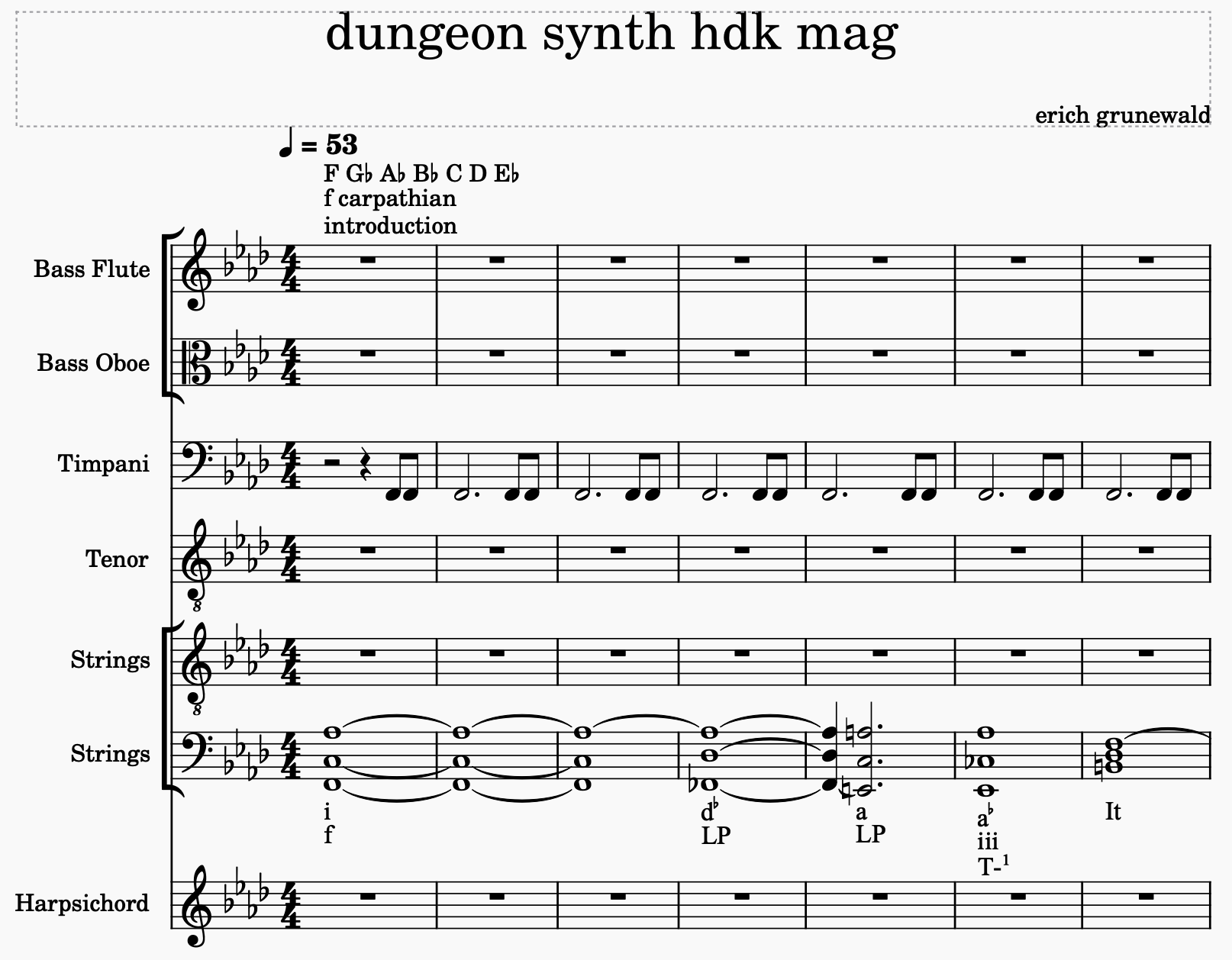

How does that work in practice? For ADA, for example, I wrote the introduction partly inspired by the introduction of Brahm’s Symphony No. 1, it’s true, but really using only motives based on ideas occurring later on. For example, the dactyl rhythm in the timpani is taken from the first theme, and the very first notes of that theme, which appear just as the introduction has ended, are the model for the ascending line in the harp-like instrument of the introduction.

The thing I find most pleasurable here is writing transitions between two contrasting passages. When doing this, I again follow Alan Belkin’s advice:

- Find the differences between the two passages.

- Proceed by changing only one element at a time.

- Introduce the new ideas while at the same time recalling something already in the listener’s memory.

I don’t write music from beginning to end – I just start editing or continuing on a section that I feel like editing or continuing on. I work on a passage until I am happy with it. If I cannot become happy with it, I delete it and start over. Deleting passages can and should feel liberatory.

Instrumentation #

The dungeon synth I make is mostly orchestral in style. Some of it I suppose you could call chamber music. But these comparisons with traditional European art music are flawed, because dungeon synth is made almost exclusively with synthesisers, which sound very different from traditional instruments like violins or flutes. A symphony has many individual parts and is scored for an orchestra with many instruments. If you try to make a track with that many synthesisers, it will probably sound like a mess, because synthesisers are really rich, full-bodied and laced with overtones. What’s more, synthesisers are usually not recorded in a giant hall, so they sound much closer than orchestral instruments.

The lesson being: for dungeon synth, I find, you can get away with scoring music for only a few parts. I wouldn’t use more instruments than I did for ADA, which I scored for bass flutes, bass oboes, tenor voices, strings, harpsichord and timpani. The precise instruments don’t matter – it’s just important that they sound something like the synths I have in mind for each part in the final piece.

Orchestration #

So at some point, as I am writing the music, I want to get an idea of how it will actually sound with real synths instead of MuseScore’s shoddy MIDI instruments. So I export the project to a MIDI file and import that file into Ableton Live[3]. (Actually, after exporting and before importing, I run the MIDI file through a neural network of my creation that assigns velocity values to all notes, in other words “humanises” the music. This step, though it adds a lot, can be skipped.) In Live, I experiment with various synths for various instruments. I usually use presets, and only sometimes modify these. I think I often try over a hundred presets from various synths until I find something I am happy with.

This, for me, is the hardest and – maybe not coincidentally – least fun part. But it is important. I find that you can do almost anything in the previous steps and still have it sound like dungeon synth with proper orchestration. Dungeon synth is really an atmosphere more than a style of music, and this atmosphere is based largely on timbre.

Addendum 2023-12-14: With version 4, released at the end of 2022, MuseScore now supports the use of VST audio plugins. That means I can now compose directly using the final sound I intend each part to have, so long as I stick to software synths. This is a great convenience and relief.

I own a few hardware synths but when making dungeon synth I only use software synths. Some of the ones I use are:

For ADA, I ended up using one of Erang’s string pluck samples for the harp-like instrument and various Korg M1 sounds for the other parts: “Morocco” for the bass flute, “Vel.-Choir” for the bass oboe, “Timpani” for the timpani, “MassiveChoir” for the tenor voices, “Stringorch” for one string part and “Orchestra1” for another string part.

I also add atmospheric sounds at various parts of the track. These are usually sampled recordings from fantasy video games.

Mixing #

The main goal I have with mixing is to give the thing clarity and to make it possible to hear the individual parts – why write passages in a contrapuntal style if the listener can’t hear it? This is kind of difficult with dungeon synth, which tends to sound pretty murky. I don’t have a solid way around this. I usually just tweak stuff until I have reached something like a compromise. Some less obvious things that I find helps give clarity and just generally create a nice sound:

- I turn the lower frequencies mono for all tracks. This makes the mix sound less muddy. You can do this with sends and buses, but I use a plugin called VUMTdeluxe which makes it easy.

- I make heavy use of equalisers, sometimes just to shape the sound of a synth or sample, but sometimes also to give clarity to the mix. This is an old piece of advice, but one thing that works well is, instead of boosting some instrument that is hardly audible, to attenuate some other instruments in the overloaded frequency range.

- I distribute the instruments in stereo space, panning some somewhat – not too much – to the left and some somewhat – not too much – to the right, following the ideal of the symphony orchestra.

- I use a single reverb, put in a bus channel with sends from all instruments leading to it, for the whole track, again to simulate the sound of a symphony orchestra, where there is only the reverb of the orchestra hall. That is, I don’t put reverb effects on the individual instrument tracks (though sometimes a preset uses the synth’s reverb module, in which case, eh, if it sounds good, I’m not going to be a purist about it …). Impulse Record’s Convology XT is an excellent reverb plugin.

- To reduce the problem that comes with the really rich and full-bodied sound of some synths, I use TDR Labs’ Proximity plugin, which does a bunch of stuff like filtering and attenuating the sound to make it appear more distant.

- I use the Waves’s J37, PuigChild and CLA-76 plugins to introduce warmth.

I am not an expert at this stuff, however, so take my advice with a grain of salt. In a perfect world, I could outsource this too to an AI.

Conclusion #

If this all sounds like a lot of work, that’s because it is. I spent many many hours making ADA, which is only 15 minutes long. It tries to optimise for quality, not quantity. If that seems daunting, try using this method to make a very short track, maybe with only two brief contrasting themes, or even with just a single theme (though even in the shortest of pieces you will need some contrasting material). At worst, you will have composed a miniature. But compositions have a tendency to expand organically as you create them, and you may well end up with a longer piece by accident, so to speak.

Footnotes #

Belkin, A. (2018). Musical Composition. Yale University Press. ↩︎

Toussaint, G. T. (2005, July). The Euclidean algorithm generates traditional musical rhythms. In Proceedings of BRIDGES: Mathematical Connections in Art, Music and Science (pp. 47-56). ↩︎

I don’t necessarily recommend Ableton Live over other, similar products. It’s just what I’m used to. I used to use Logic Pro and that was fine, too. ↩︎