This post is part of a series on relatively unknown European art music composers:

- Good Works by Lesser-Known Composers

- ➾ Good Works by Lesser-Known Composers 2

Good Works by Lesser-Known Composers 2

Herr, warum trittst du so ferne; Herr, sei mir gnädig, denn ich bin schwach … Ich bin so müde vom Seufzen … Ich bin ausgeschüttet wie Wasser … Mein Gott, mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen?

Lord, why do you stand so far off; Lord, have mercy, for I am weak … I’m so tired from groaning … I’m emptied like water … My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?

– Excerpts from the Book of Psalms

John #

He was born somewhere in England, probably during the reign of Henry VI, or maybe Edward IV – in a time of war, banditry and God, anyway. He would have had a mother and a father. He may have been a King’s Scholar at Eton or Coventry. He may have been a canon of this or that parish church. He may have been a husband, brother, father, or not. We don’t know much about John Browne, but we know this: he wrote music not like a warrior or like a bandit, but like an angel.

(This is a drawing by Viktoriia Shcherbak of what Browne might have looked like; Browne’s true likeness has not survived.)

Only a handful of works by Browne are known to us, all of them through the Eton Choirbook. One of those is Stabat iuxta Christi crucem, an antiphon scored for four tenors and two basses, an almost unheard-of combination. The absence of higher voices meant Browne was limited to a narrow vocal range – two octaves – as a result of which each chord is shimmering and full-bodied, chords, by the way, which present one surprising and beautiful harmony after another.

Structurally it’s made up of two parts, the first in 3/4 time and the second in 4/4 time. Each part opens reservedly, with two voices only, but gathers in emotional power as more voices join in. The best image I can think of is a little stream high up in a mountain trickling downhill and gathering force until finally it is a great current of feeling pouring out into the sea.

Textually it’s a Marian hymn describing, quite graphically, the Blessed Virgin’s experience as she stood by the Cross watching her Son die. It ends with a supplication

Gentle virgin, holy virgin,

sinners' hope, vine's way,

virgin full of grace,

bid your son, implore him

to without delay grant those of us

who are his servants joy.

where the final word – gaudia – marks the end of the composition as it’s introduced in imitation and then beautifully elaborated in the span of some 12 bars … This one’s different from all other Renaissance polyphony I’ve heard. It is one of my favourite artworks of any genre, medium, style or era.

As far as I know, Stabat iuxta has been recorded only once, by the Tallis Scholars on Gimmell Records, but it’s an extraordinary recording, maybe perfect.

Heinrich #

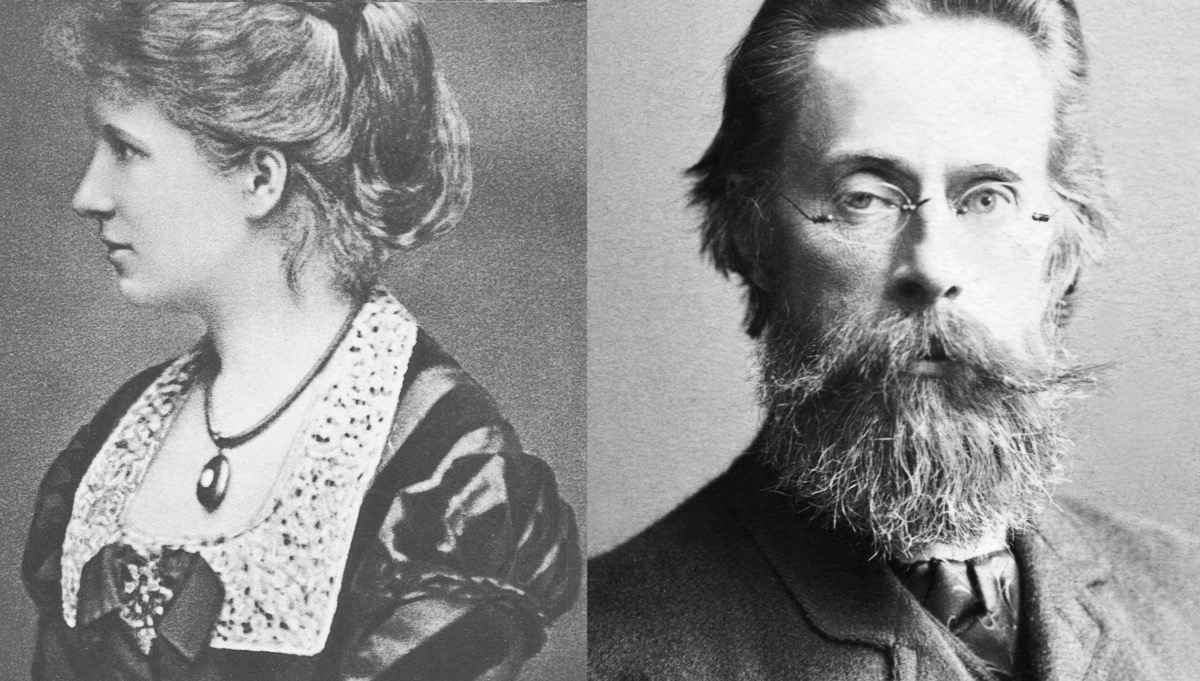

They all agree that she was talented, witty, gracious and beautiful. She was an excellent pianist, though she didn’t play for the public. Elisabeth von Stockhausen had every gift except that of health. When she married Heinrich von Herzogenberg in 1868, he must have thanked his lucky stars. But after two decades of happy marriage, she fell ill, having exerted herself nursing her husband back to health from some or other illness.

“My wife’s recovery is slower this time than ever before. She has been in bed six weeks, and the doctor cannot convince himself whether this inertia is a good or a bad sign”, he wrote in a letter to their friend Johannes Brahms. And a year later, “Her sufferings hurt me more now that I have no hope to keep me up and deceive me. My suffering has given me no time to realise my own position, and, indeed, I have buried myself in work, hoping not to be aroused from it again.” By then she had died, aged 44, in Italy.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg worked through his grief by making music. He completed a sacred cantata, the Totenfeier, a year after Elisabeth’s death. It’s a fine work, clearly influenced by Bach’s cantatas and oratorios, but at the same time plainly Romantic. It’s a little uneven, but there are some real highlights: I especially like the introduction, the first recitative and aria for bass (which uses snippets of text from the Book of Psalms, as quoted above) and the third section, which alternates between hushed passages for alto and organ and mournful laments by the chorus and orchestra.

Herzogenberg’s Totenfeier has been recorded for CPO by the Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha with Matthias Beckert conducting.

Paul #

In photographs his face looks like a statue, pale, stern, though somewhat liquefied by age; he has the hawkish nose, high hairline and pouchy, sorrowful eyes of an ageing philosopher or politician, and looking at him you almost feel you’re being deceived: you think, here’s a strong face, hard like stone, but then realise it’s made of pudding. In life he was a member of Alfred Rosenberg’s Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur and vice president of the Reichsmusikkammer (having succeeded Wilhelm Furtwängler after the latter resigned, his relation with party leaders having become unbearable).

As Paul Graener benefitted from the Third Reich during his life, so his reputation suffered from it after his death.

On the one hand, the Nazis’ control of the entire cultural sector, and the corollary death of free German culture, stifled music in the Reich.[1] On the other hand, German music to some extent carried on by sheer momentum, and having been a bona fide Nazi meant obscurity after the war, so you might on that basis expect there to be an obscure gem or two produced by composers of the Third Reich.

Aus dem Reiche des Pan, published in 1920, is definitely obscure, and something of a gem. It’s an orchestral suite in four parts:

- “Pan dreams in the moonlight” and

- “Pan sings of love and longing”, two brief, evocative parts followed by

- “Pan dances”, a dance – everything so far reminiscent of Max Reger – and

- “Pan sings the world a lullaby”, a longer closing part that sounds like a mixture of Richard Wagner and Ralph Vaughan Williams (which is surprising, given that Vaughan Williams doesn’t usually sound very German, and Graener, though he did live in England for over a decade, doesn’t usually sound very English). It gives a feeling that German Romantic music sometimes does – one of something deep and consequential happening.

Aus dem Reiche des Pan has been recorded by the North German Radio Philharmonic Orchestra with Werner Andreas Albert on CPO.

Ruth #

One year after the dour-looking German published his tone poem about Pan, an English girl was born into a musical family in a seaside town in East Sussex. She, the girl, learned to play the piano and oboe at a young age, and began composing at the age of eight. It seems she had a talent for everything, including determination. But Ruth Gipps had fallen into a crack. She was a Romantic composer after the Romantic style had gone out of fashion, and a woman composer before women were fully accepted by the European art music establishment.

Ambarvalia is an orchestral piece, very Anglo-Saxon, recalling English greats like Frederick Delius and (again) Ralph Vaughan Williams (who was also Gipp’s teacher for a period of time). The main draw and focal point is a serene, very memorable main theme. From there the piece progresses without straying very far in style or mood, though a contrasting middle section is a bit more mysterious and understated. The title is a reference to a pagan Roman fertility rite. It’s a very good composition.

Ambarvalia was recorded for the excellent SOMM Recordings a few years ago by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra with Charles Peebles.

References #

Footnotes #

Cf. Furtwängler’s letter to Goebbels: “Ultimately there is only one dividing line I recognise: that between good and bad art. However, while the dividing line between Jews and non-Jews is being drawn with a downright merciless theoretical precision, that other dividing line […] seems to have far too little significance attributed to it” (Prieberg 1994). ↩︎