Everybody Is Vulnerable, Nobody Is Powerful

Edit 2022-10-23: This post is almost completely free of evidence and I’m unsure whether it points at something real. I now give ~50% probability that the proposition "compared to 10 years ago, powerful people downplay how much power they have, and present themselves as more vulnerable than they are" is true. Some things that I didn’t do but that may have been useful were comparing within-a-reference-class official statements now and then, looking for arguments for the opposing view and asking other people what their impressions were. I have however decided to leave the post mostly as-is, except with this caution up front and stylistic excesses somewhat reined in.

I have hunkered down in the azalea bushes, slipped the binoculars before my eyes and spotted a trend. The trend is this: in these times, everybody is fragile, everybody is vulnerable and nobody has any power. People and especially nations have everywhere and at all times seen themselves as the victims of unjust harm, but that has rarely meant that they were also powerless. Now the most powerful also have the least agency. Trump was constantly thwarted by the deep state; von der Leyen and her merry band of bureacrats would have nailed the vaccine rollout if only it weren’t for AstraZeneca; Israel and the IDF, anxious and exhausted, are bullied by their enemy into sending airstrikes on Gaza; Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping blame the West for their problems; in the West, CIA operatives suffer from anxiety and imposter syndrome; and this is not to mention the people from whom this sort of language has been appropriated, those whose lives are upended by the mildly offensive.

The purpose of this is obvious – if you are powerless, you are not responsible for bad states of affair. States of affair today have complex causes. We can’t always look at one and say that some or another person or nation caused it and is fully responsible for it. What we can do is look at one of that person or nation’s actions to see if it had good or bad consequences. Maybe what the powerlessness rhetoric is saying is less “our actions don’t have any effects, therefore we aren’t responsible” and more “our actions have good effects, but they are cancelled out by the negative effects of X and Y”. Either way, it’s a tactic used to avoid being held accountable.

Related to this powerlessness, as the obverse of a coin is to the reverse, is a new vulnerability among the mighty, of which recent events have given us another example: on the morning of 12 May, the following tweet was published by the official account of the State of Israel, though doesn’t it sound more like it came from the Instagram feed of an influencer?

It’s been a difficult night for us, exhausted after spending hours in bomb shelters, but waking up to so many messages of support from you guys helps. Thank you ♥️.[1]

Or consider Freddie deBoer’s description of social justice politics:

The movement that I grew up in that would eventually come to be called the LGBTQ movement once held that queer people were strong, that they were so much stronger than they were given credit for by society. The foundational assumption of the LGBTQ movement of today is that people in those communities are permanently and existentially weak; any insult or injury to them, no matter how small, will inevitably be a life-altering trauma. They are considered devoid of resilience and incapable of recovery. They are portrayed, by their loudest allies, as lost little children, wounded by language, utterly vulnerable at all times to those who could derail them with a bad look.

Freddie deBoer argues that obscuring the agency of some minorities in this way is patronising and corrosive. He is writing about people who really are more likely to encounter challenges like discrimination or being born into poverty and so on. I am writing about people and groups of people who are neither powerless nor vulnerable, but who’ve taken this language from social justice advocates and, like them, use it to gain power and sympathy. And the more powerful these people are, the more absurd is their conduct.

Undergirding the vulnerability is a desire for sympathy. If in Renaissance Italy it was better to be feared than to be loved[2], it is now better to be pitied than to be admired. This may be why everybody is now vulnerable: it is a way of receiving commiserative attention. They just want us to feel sorry for them, because bad things keep happening to them, things completely out of their control. And “every ass thinks his own load heaviest”[3].

I admit that this is speculative. Is this thing, if it exists, even new? Sure, the old monarchs claimed absolute power, and maybe past heads of state did speak more often as if their actions had effects, but surely people in power have always had excuses for their shortcomings? Surely these techniques ought to have always been useful for powerful agents?

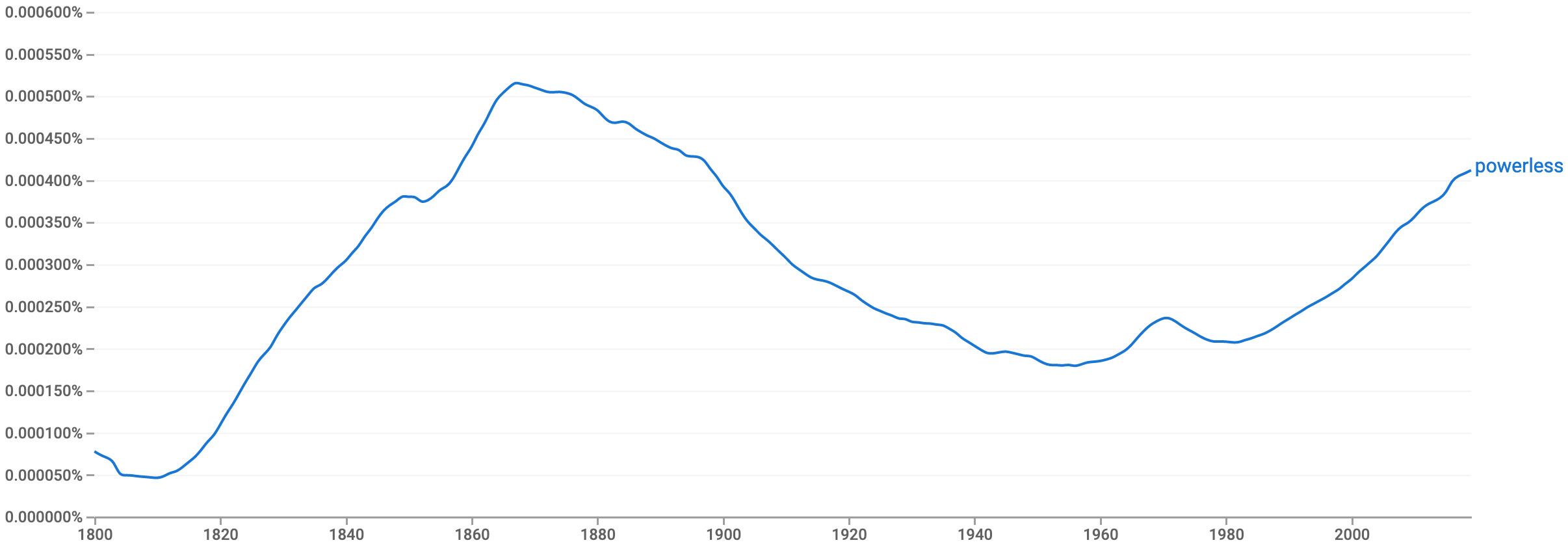

If we ask the Oracle of Mountain View, we see that talk of powerlessness has been increasing for 40 years:

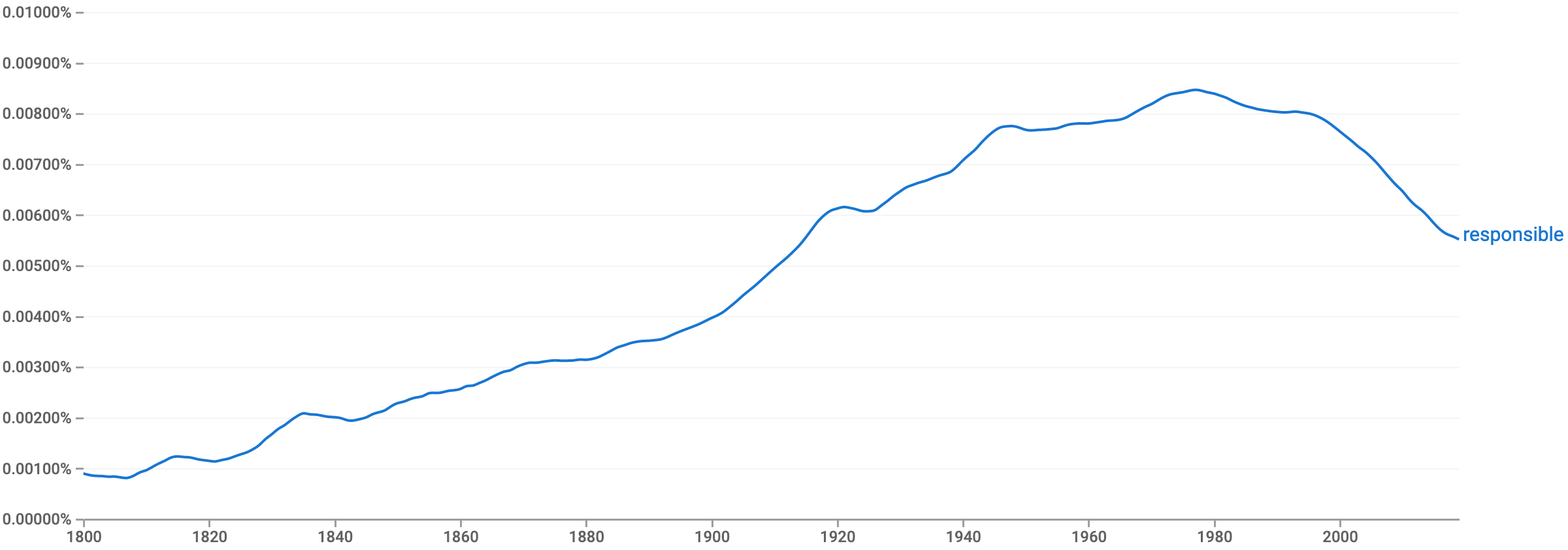

And for 40 years talk of responsibility has been in decline:

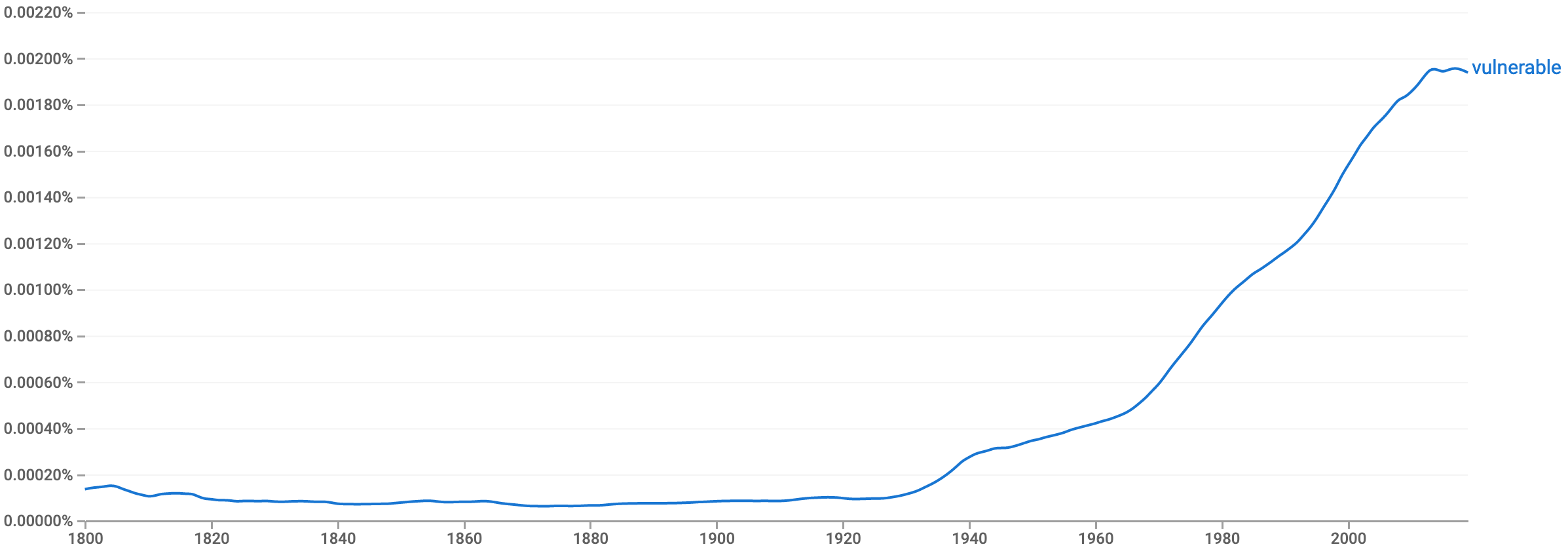

And ever since the Depression talk of vulnerability has gone up:

If this is new, one reason could be that we no longer view powerlessness as weakness in the same way that we used to. I am thinking, for example, of the Russian President in The Sum of All Fears who would rather take the blame for triggering a nuclear war than let the world know that he was disobeyed by one of his generals, that his authority was weak. (Or something like that; it’s been while since I saw it and I trust you’ll believe me when I say I’m not going to do so again.) That kind of face-saving behaviour seems rare today.

A second reason might be that the media today scrutinises everything more closely, and that it’s easy to spin any outcome into a critique of the plausibly responsible. For example, after Trump and Jared Kushner brokered a deal between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, the Jacobin headline read Israel’s Honeymoon with the United Arab Emirates Is Grotesque. After the first Nuclear Security Summit, hosted by Obama in 2010, some Republicans complained that its logo was reminiscent of the Islamic crescent moon. (I’m not agreeing or disagreeing with these things; I’m only using them to show that it’s nearly impossible for a politician to earn praise from the other side.)

There are two things at play here:

- If your actions aren’t properly scrutinised, you have less of a need to deflect responsibly.

- If you feel that your successes get the same negative spin as your mistakes, what exactly is the advantage of taking responsibility? No one who wasn’t already on your side is going to give you credit for the good things you do, so there’s little benefit in being associated with the effects of your actions.

Sometimes (but not always) people and groups of people say they’re powerless because they feel they’re victims of unfair and unjust treatment. China’s and Israel’s protestations don’t seem to me to be the product of victimhood mentalities, though both nations do cultivate those. They look more cynical than that, maybe because they’re powerful relative to their neighbours, or because they try to project strength (which implies power) at the same time as they claim to be at the mercy of others – think Israel’s pride in the Iron Dome and the IDF and Xi Jinping’s declaration of victory against the coronavirus last fall:

The CCP’s strong leadership is the most reliable backbone when a storm hits. The pandemic once again proves the superiority of the socialist system with Chinese characteristics.

Addendum 2022-10-23: This may have been a somewhat premature victory lap.

Compare that to the tone of its response to a U.N. tribunal – of course produced for a different audience – on its claims to the South China Sea a few years ago:

“China is the victim of the South China Sea issue”, writes Yang Yanyi, the Chinese ambassador to the European Union. The case is “a vicious act”, says Xu Hong, the director-general of the foreign ministry’s Department of Treaty and Law. Xu Bu, China’s ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, argues that the conspirator behind the scenes is a “dictatorial and overbearing” America that “cannot tolerate others challenging its global hegemony”.[4]

Bar-Tal et al. write that victimhood among nations and peoples is unrelated to power[5] – you can be (or claim to be) a victim even if you are powerful:

A sense of collective victimhood is unrelated to the strength and power of the collectives involved in intractable conflict. Collectives that are strong and powerful militarily, politically and economically still perceive themselves as victims or potential victims in the conflict. The self-assigned status as the victim does not necessarily indicate weakness. On the contrary, it provides strength vis-à-vis the international community, which usually tends to support the victimized side in the conflict, and it often energizes members of a group to take revenge and punish the opponent.

This has happened in the case of Russians in the Chechen conflict, Americans in the Vietnam War, Israeli Jews in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Turks in their conflict with Kurds, or Sinhalese in the Sri Lanka conflict.[6]

As I see it, victimhood feeds into a number of other traits, two of which are powerlessness and vulnerability (though one can make claims to these without claiming to be a victim). These in turn allow one to avoid being held accountable and to garner sympathy for one’s predicament. What has allowed this to happen, so I speculate, is an increased social acceptance of powerlessness and vulnerability. In many ways that acceptance is a good thing – a person’s or group’s value should not be determined based on how powerful or protected they are, at least not to a large degree, because those things are largely out of their control – but it also allows bad actors to exploit onlookers by making claims to these things for purely instrumental purposes, a phenomenon the absurdity of which is revealed now that it is taken to its logical endpoint – now that it’s appearing among some of the most powerful people and nations on Earth.

Footnotes #

On 11 May, one Israeli was killed and four Palestinians; on 12 May, four Israelis and 21 Palestinians were killed. But of course that is irrelevant here. What the PR crew who wrote the tweet is trying to do is conjure a mood. ↩︎

Though apparently Machiavelli thought it was best to be feared and loved, and only if that wasn’t possible was fear to be preferred. ↩︎

Grayling, The Good Book: A Humanist Bible. ↩︎

Browne, The Danger of China’s Victim Mentality. ↩︎

Bar-Tal, D., Chernyak-Hai, L., Schori, N., & Gundar, A. (2009). A sense of self-perceived collective victimhood in intractable conflicts. International Review of the Red Cross, 91(874), 229-258. ↩︎

ibid. ↩︎